Egypt

Egypt

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

This page explores Egypt’s current and projected future development, examining various sectoral scenarios and their potential impacts on the country's growth. It provides an in-depth analysis of eight sectors including demographic, economic and infrastructure-related outcomes for Egypt up to 2043. The assessment also considers the implications of the Agenda 2063 goals, aiming to offer insights into policy actions that could enhance the country's developmental trajectory.

For more information about the International Futures modelling platform we use to develop the various scenarios, please see About this Site.

Summary

We begin this page with an introduction and context to Egypt.

- Egypt is one of the 24 lower-middle-income countries in Africa. It is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and the southwest corner of Asia. It is bordered by Israel, including the Gaza Strip after its occupation by Israel in 1967, Sudan and Libya, as well as the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. Egypt’s landscape is mostly desert with some oases, with averagely very little rainfall and a hot, sunny and dry climate, dominated by the Nile river and its extremely fertile delta. Its largest cities include Cairo, the capital, Alexandria and Giza, all popular tourist cities along the Nile.

The introductory section is followed by an analysis of the Current Path for Egypt which informs the country’s likely current development trajectory to 2043, mostly comparing Egypt with its income peers in Africa. It is based on current geopolitical trends and assumes that no major shocks would occur in a ‘business-as-usual’ future.

- Egypt is the most populous country in North Africa and the 3rd most populous country on the continent after Nigeria and Ethiopia. The total population increased from 57.2 million in 1990 to 113 million in 2023. By 2043, it will be 145.4 million.

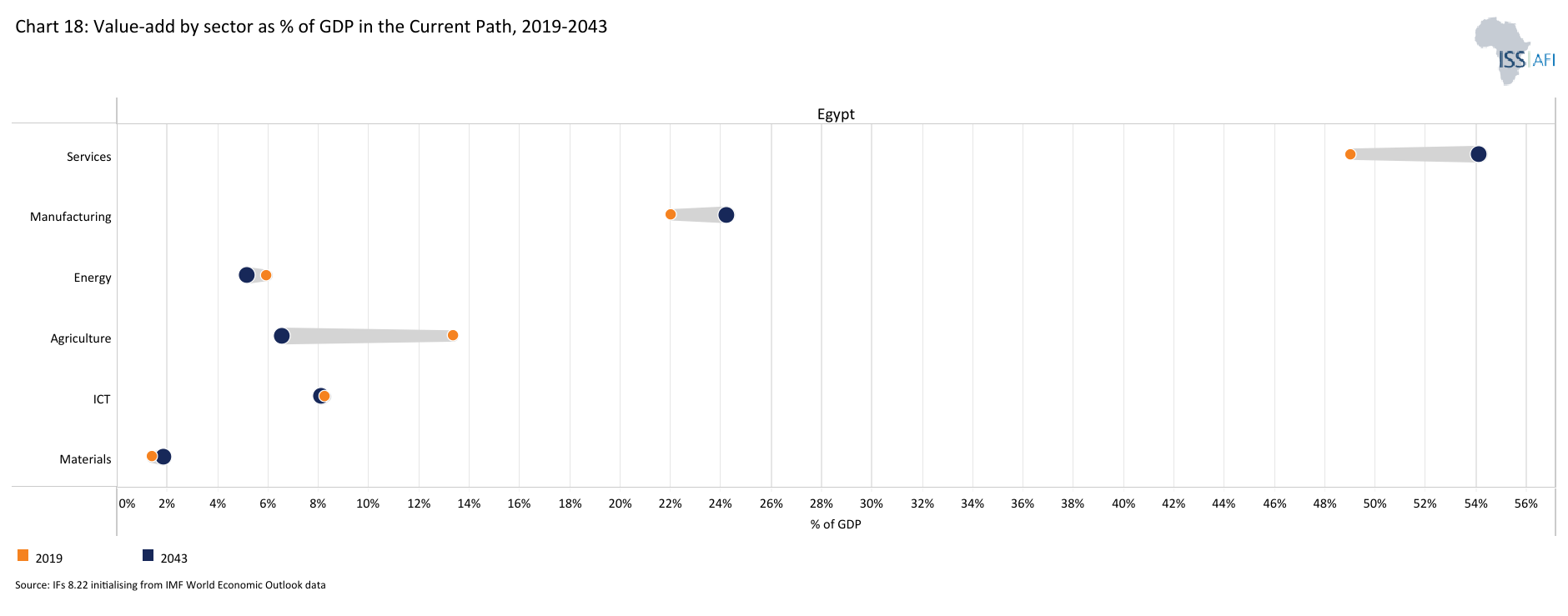

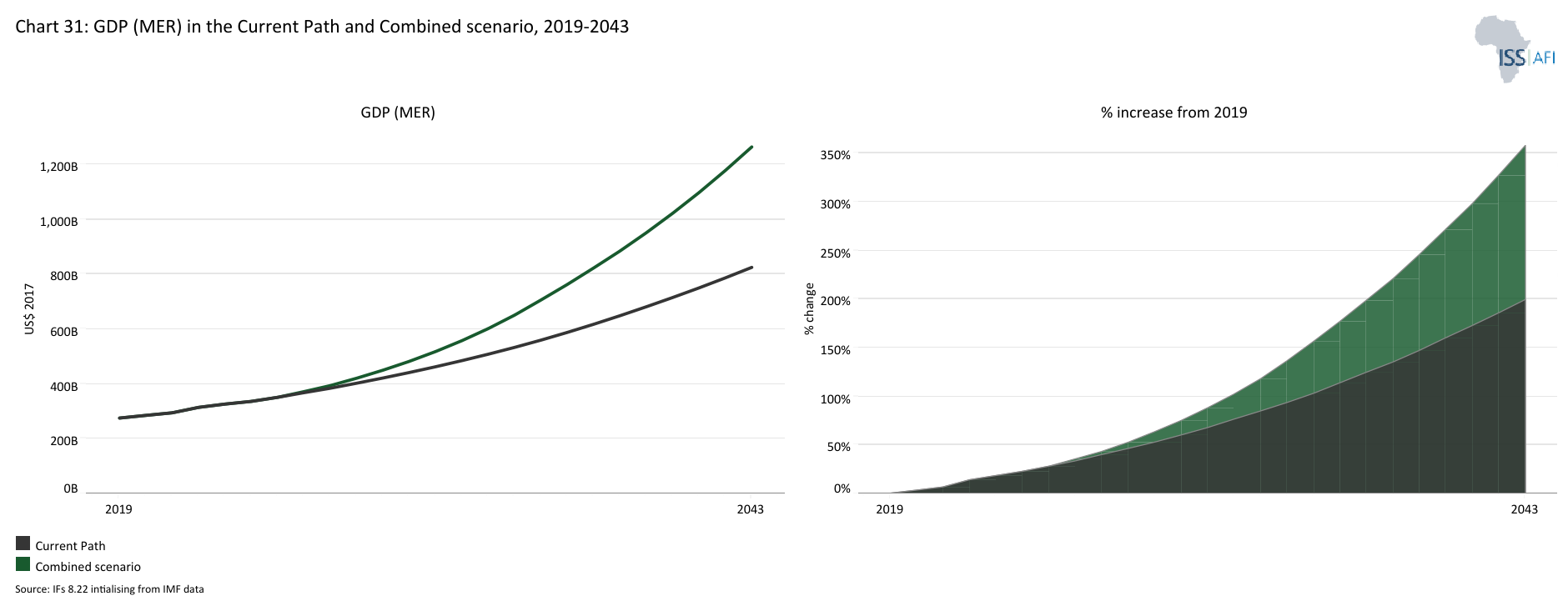

- Egypt’s GDP measured in market exchange rates (MER) almost quadrupled from US$79.9 billion in 1990 to US$327.9 billion in 2023, making it the third-largest economy in Africa after Nigeria and South Africa. Its economy depends mainly on agriculture, telecommunication, petroleum exports, natural gas and tourism. By 2043, GDP will more than double to US$826 billion.

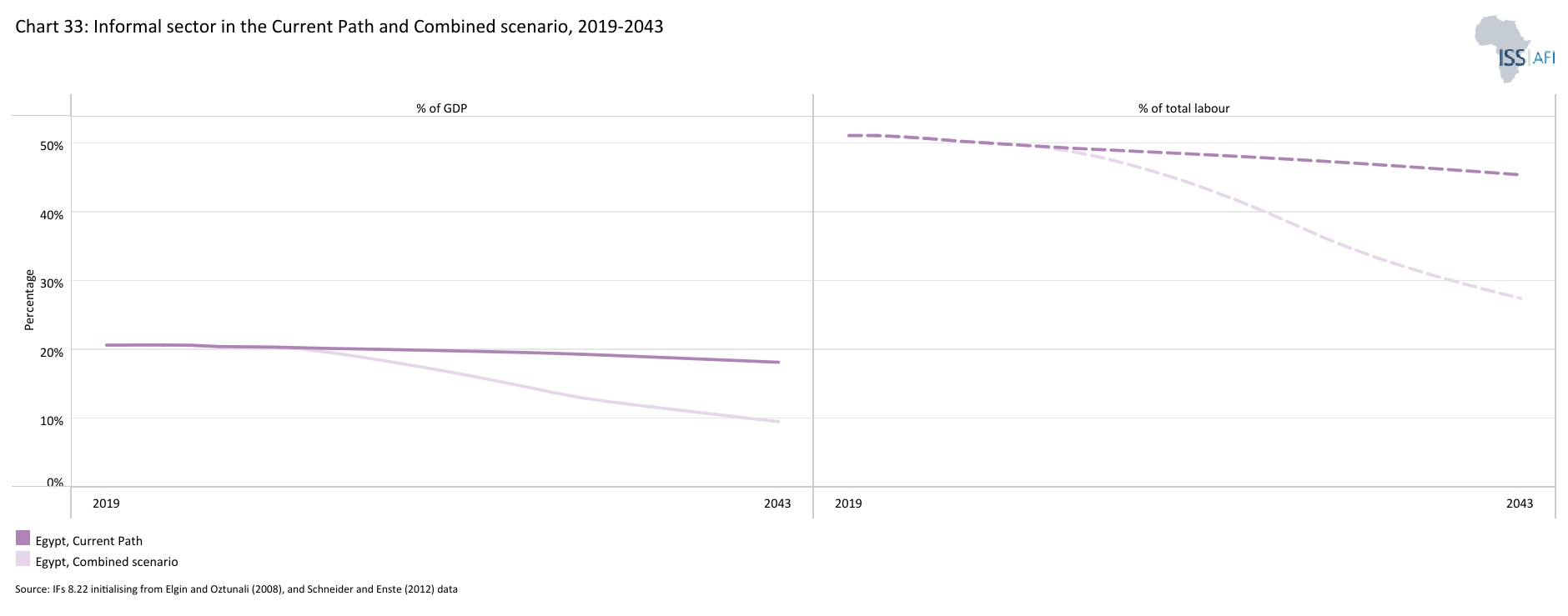

- Compared to most oil-rich Gulf countries, Egypt has a large informal sector but it is smaller than the average for Africa’s lower-middle-income countries. In 2023, the size of the informal sector was equivalent to 20.5% of GDP, representing US$67.2 billion. The average for lower-middle-income African countries is 29.2%. The size of the informal sector will slightly decline to 18.2% of GDP by 2043, equivalent to US$150.4 billion.

- Egypt has the highest GDP per capita among the 24 lower-middle-income countries in Africa. Using the purchasing power parity (PPP), it’s GDP per capita of US$12 070 in 2023 was almost twice the group average of US$6 127. By 2043, Egypt will still have the largest GDP per capita among its peers at US$17 190.

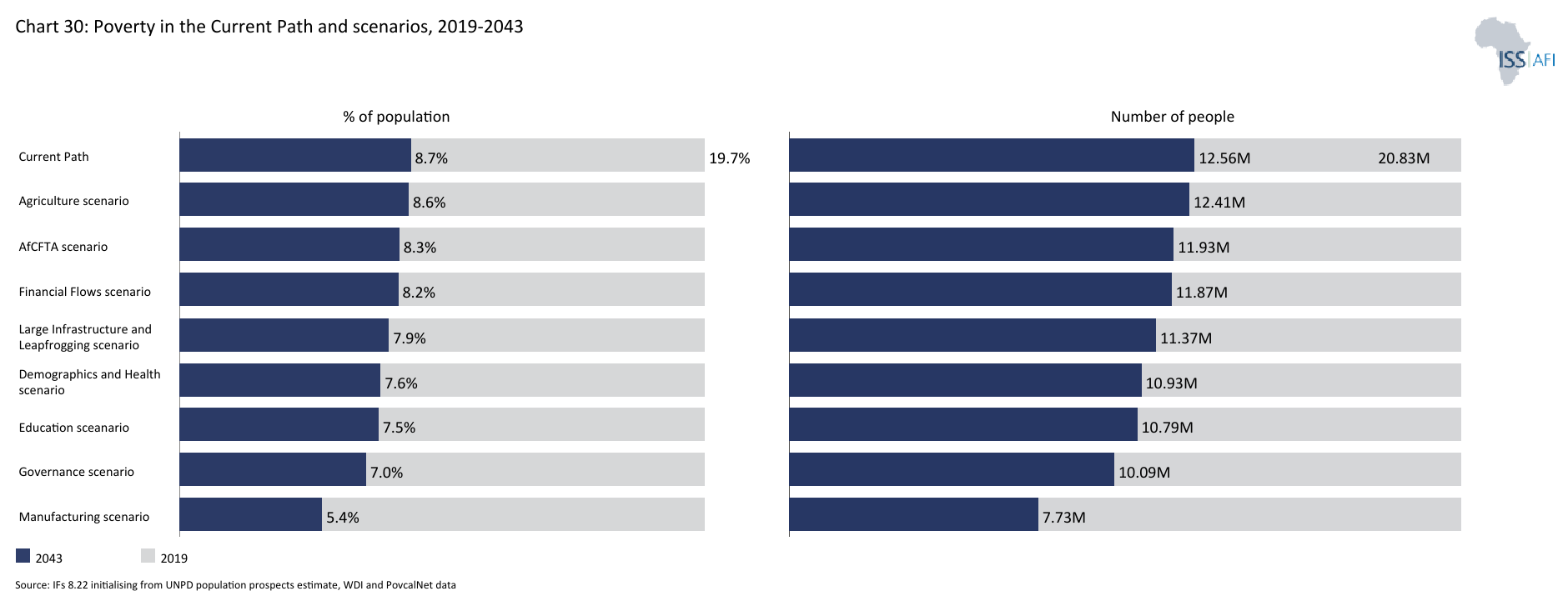

- In 2023, 18.8 million Egyptians, representing 16.7% of the population, lived below the poverty line of US$3.65, far below the average of 46.4% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. By 2043, the poverty rate of 8.7% (equivalent to 12.6 million Egyptians) will be about 24 percentage points lower than the average for lower-middle-income countries in Africa.

- The Sustainable Development Strategy: Egypt Vision 2030 is the broad framework for attaining Egyptians' dreams and aspirations of an advanced and prosperous nation inspired by the ancient Egyptian civilization’s achievements. Its overall vision is: “By 2030, Egypt will be a country with a competitive, balanced, and diversified economy, depending on knowledge and creativity, and based on justice, social integration, and participation, with a balanced and varied ecosystem, a country that uses the genius of the place and the citizens in order to achieve sustainable development and improve the quality of the life for all.”

The next section compares progress on the Current Path with eight sectoral scenarios. These are Demographics and Health; Agriculture; Education; Manufacturing; the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA); Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging; Financial Flows; and Governance. Each scenario is benchmarked to present an ambitious but reasonable aspiration in that sector.

- The Demographics and Health scenario will reduce the infant mortality rate from 11.6 deaths per 1 000 births in 2023 to 6.3 deaths by 2043, 1.4 deaths fewer than in the Current Path. The scenario pushes the ratio of the working-age population to dependants to 2.4-to-1 far above the ratio of 1.7-to-1 that is required to enter a potential demographic window of opportunity. In fact, Egypt achieves this minimum ratio as early as 2026.

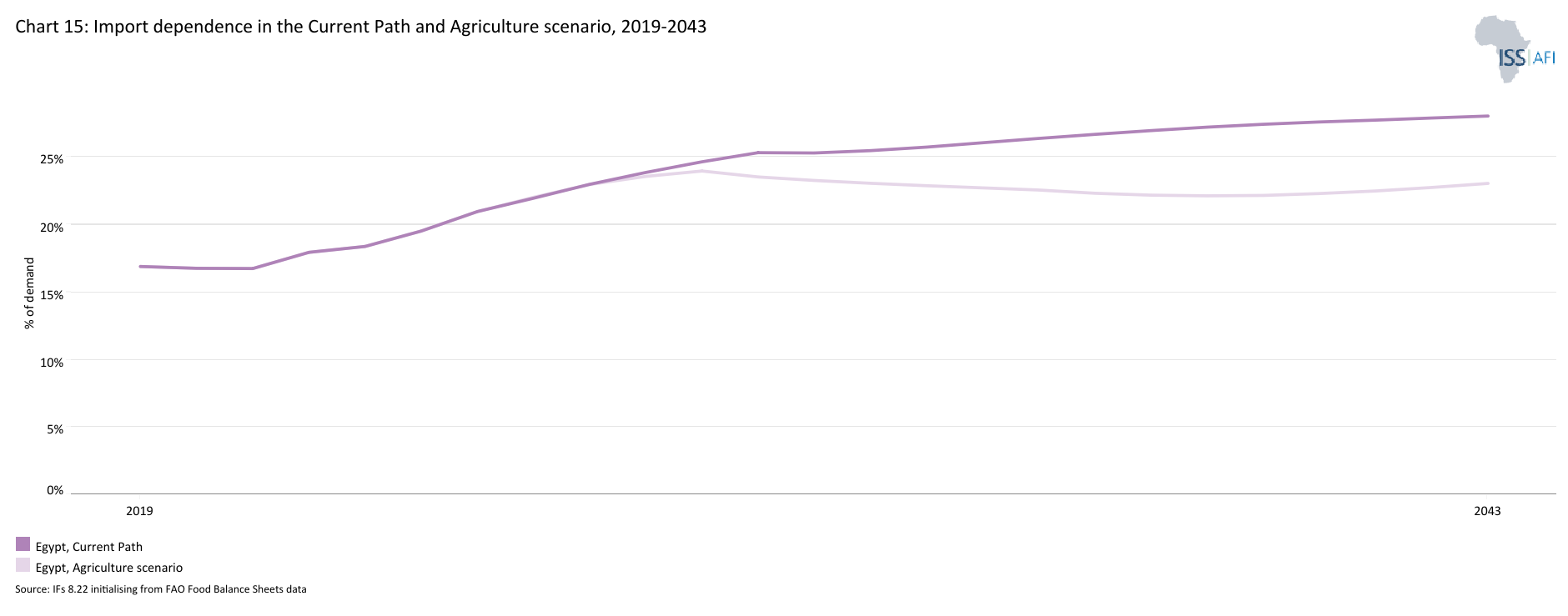

- In 2023, Egypt’s net import of crops stood at 19% of total crop demand, which was more than the average of 13.4% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. By 2043, net import of crops will reach 24.4% in the Agriculture scenario — six percentage points less than the Current Path and the average of its income-group peers in Africa.

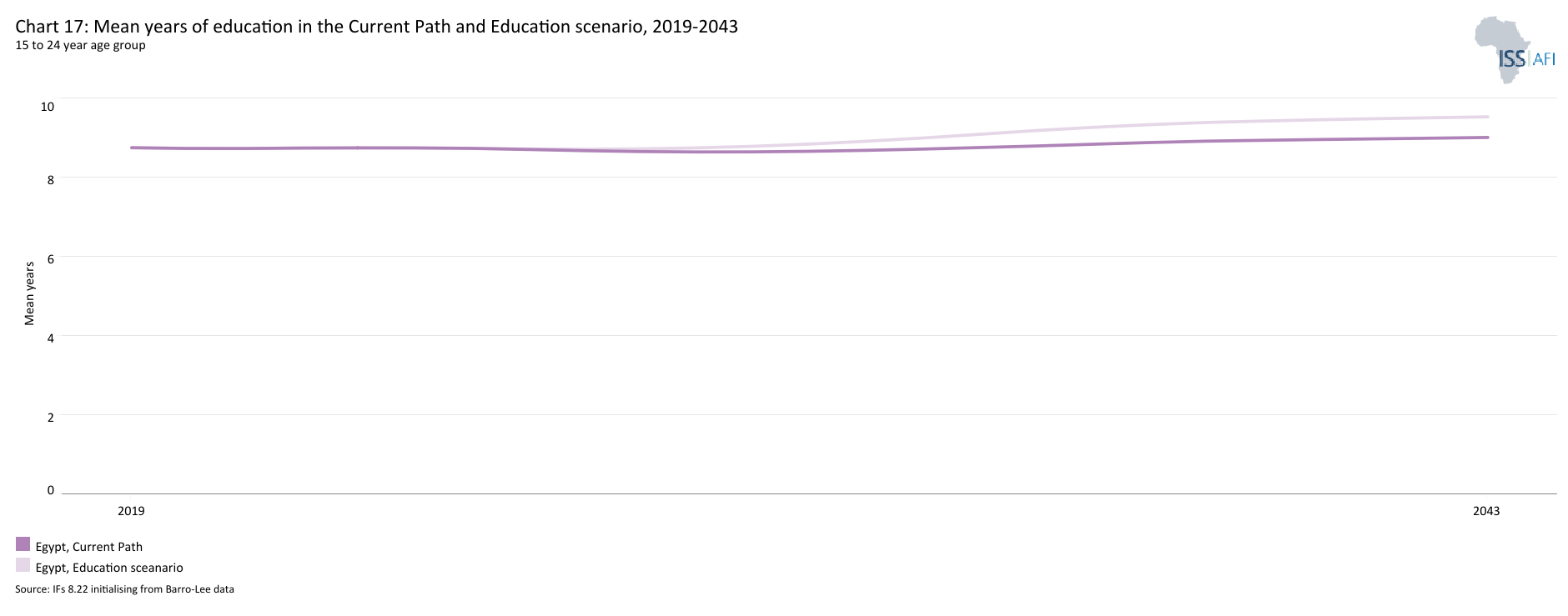

- In 2023, the mean years of education attained by adults between 15 and 24 years in Egypt stood at 8.8 years — one year above the average of 7.8 years for lower-middle-income countries on the continent. In the Education scenario, the mean years of adult education in Egypt will increase to 9.5 by 2043, 0.5 years more than the Current Path and higher than the average for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. By 2043, the scenario further increases average test scores for primary and secondary school students by 46.1% and 51.8%, respectively.

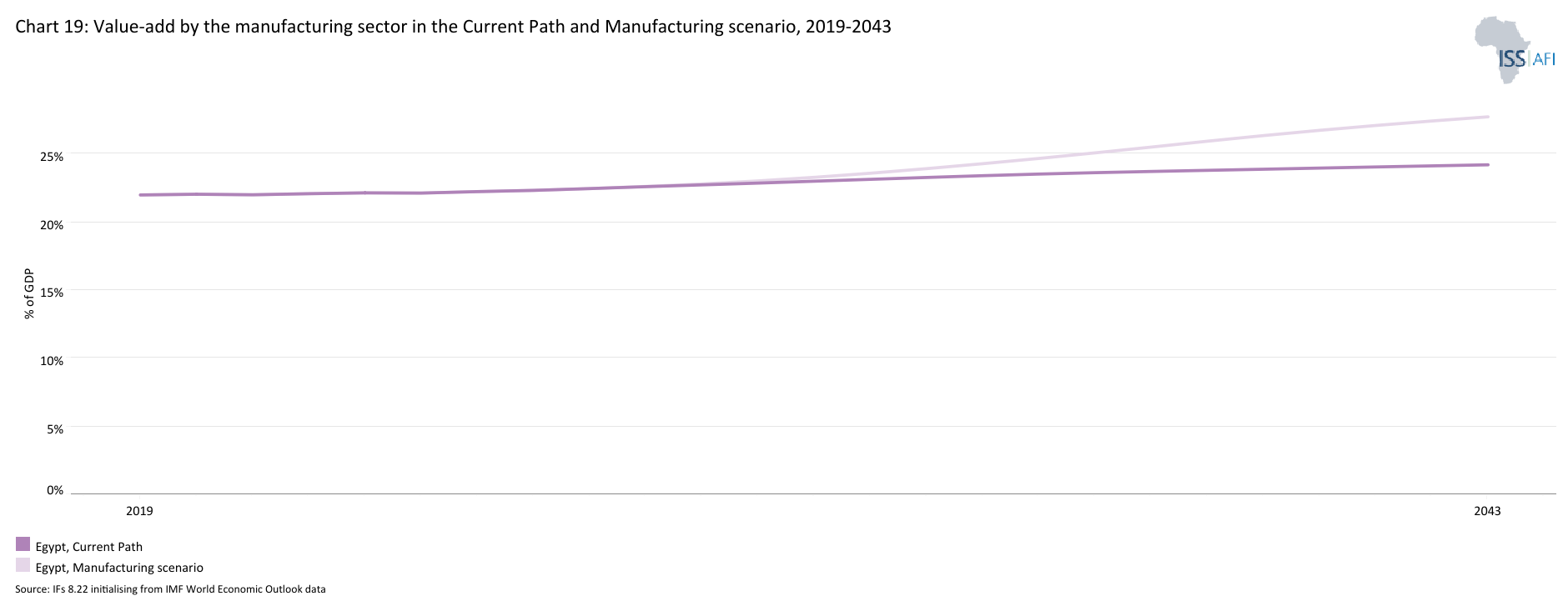

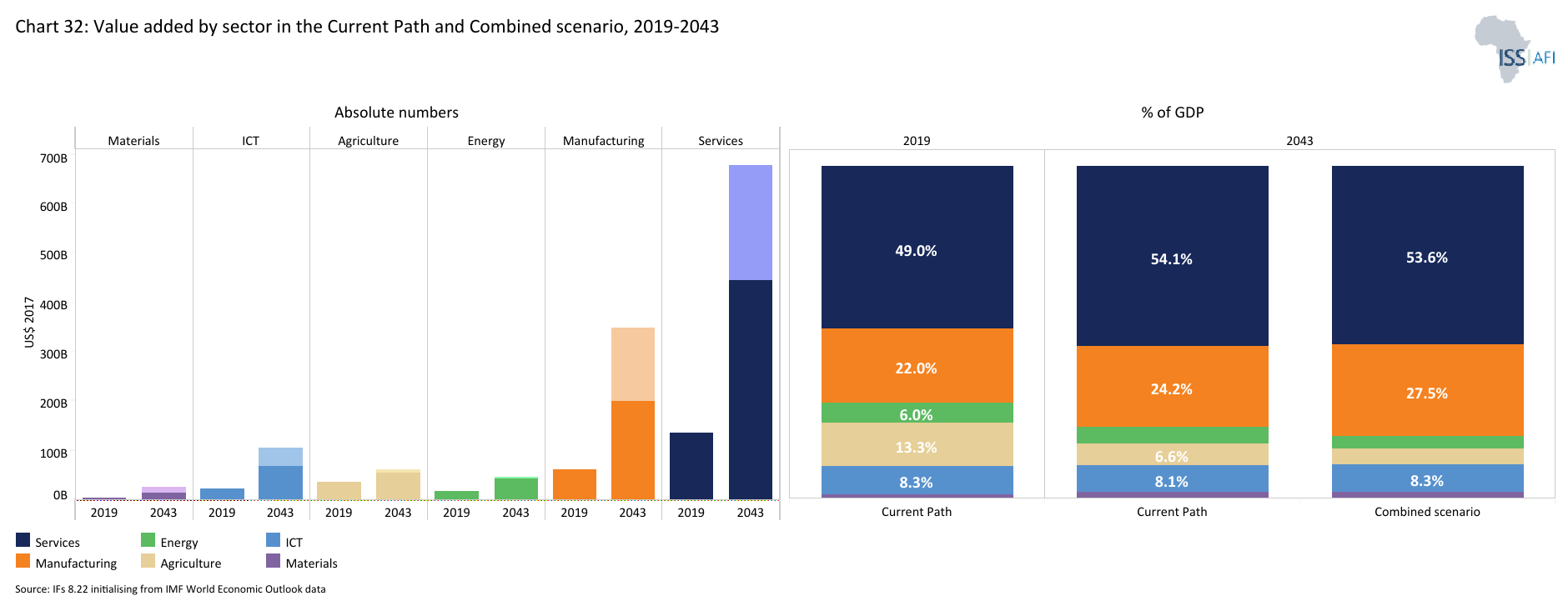

- In the Manufacturing scenario, Egypt makes substantial progress in industrialisation such that, by 2043, the share of the manufacturing sector in GDP is about 27.8% equivalent to US$256.4 billion. This will be about 3.5 percentage points of GDP above the Current Path valued at US$56.4 billion.

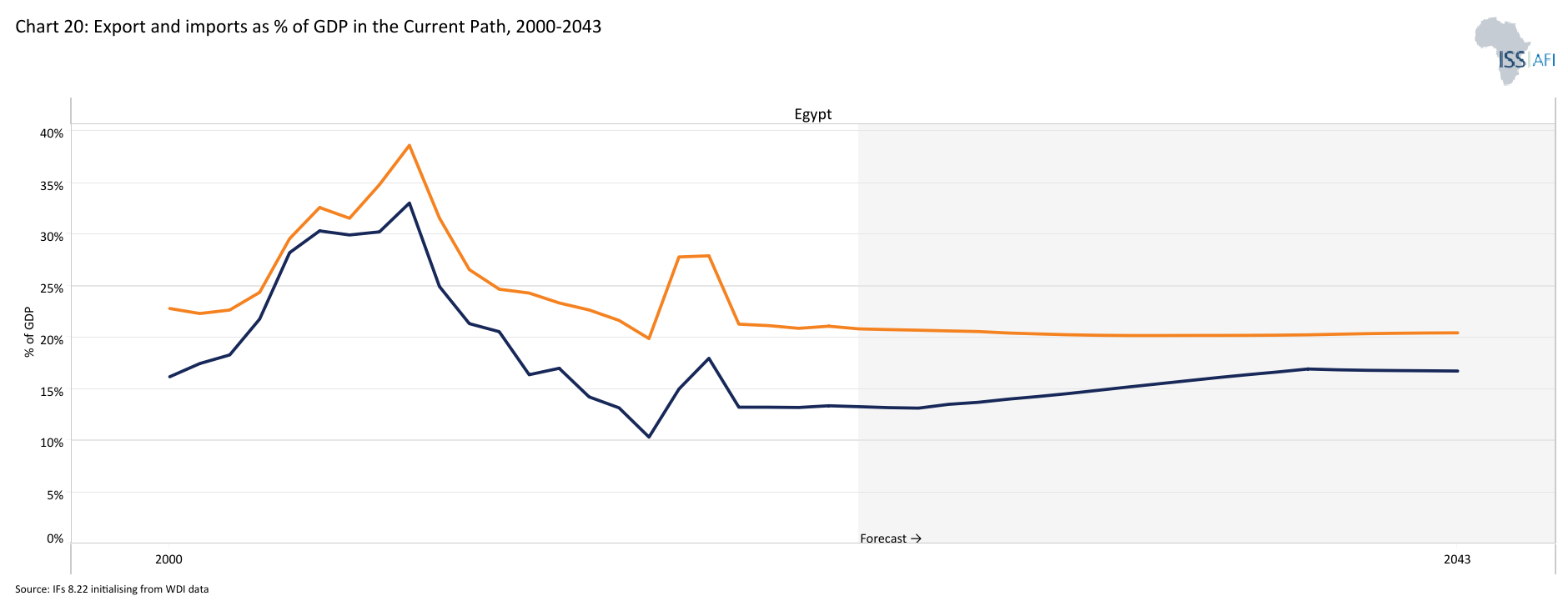

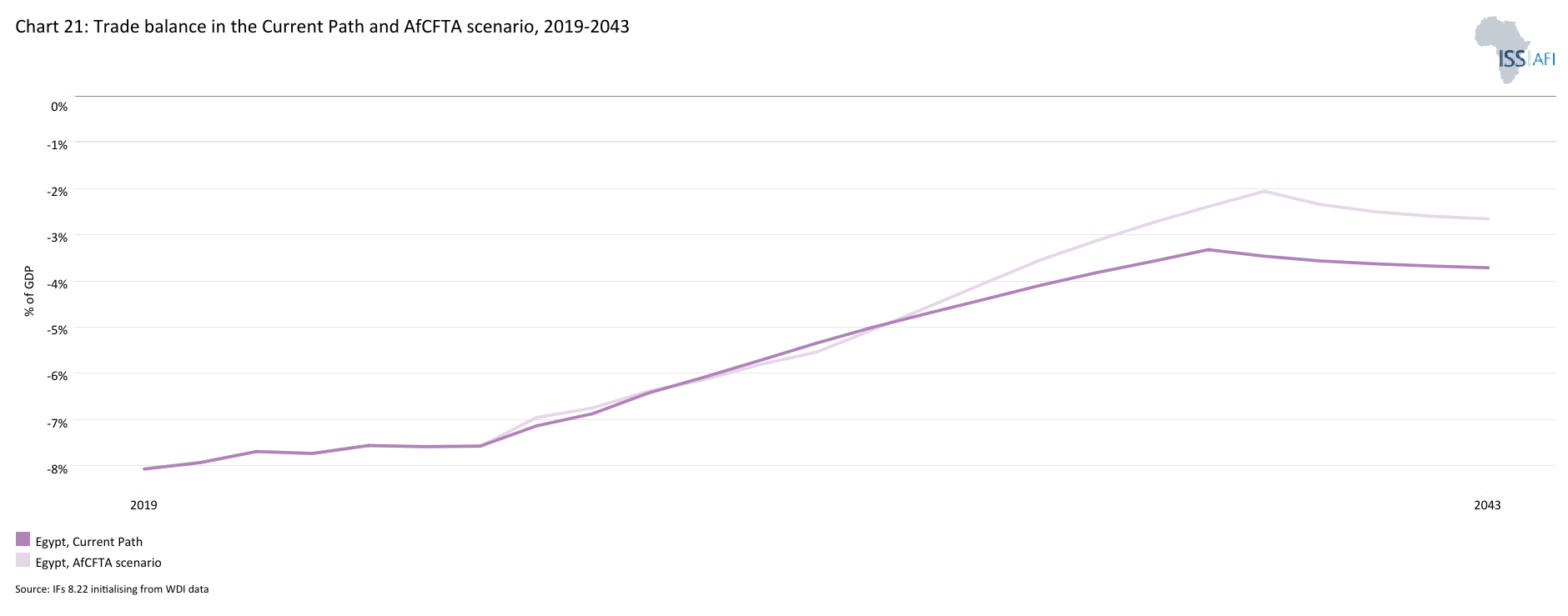

- In the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) scenario, Egypt’s trade deficit will constitute about 2.6% of GDP by 2043 instead of the 3.7% of GDP on the Current Path. Also, the sum of Egypt’s exports and imports as a percentage of GDP will reach 43.1% by 2043. This will be about 5.9 percentage points above the Current Path but 7.4 percentage points below the average of lower-middle-income African countries.

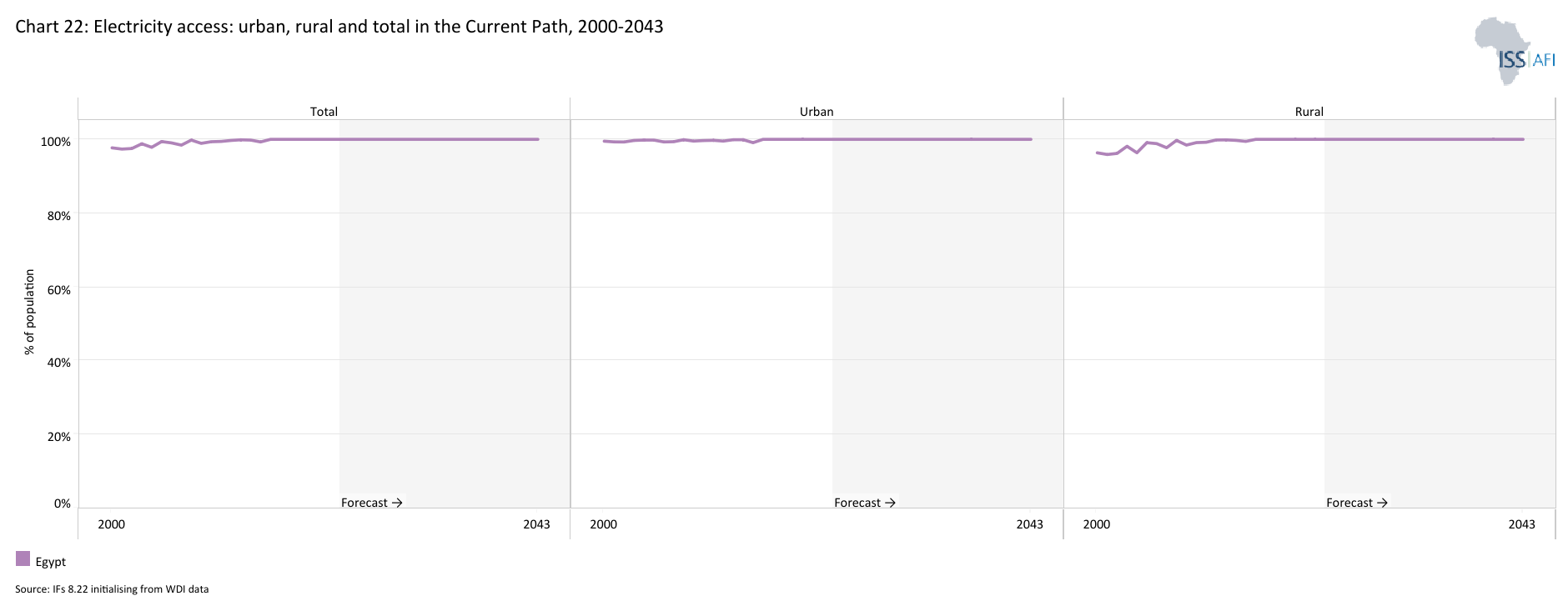

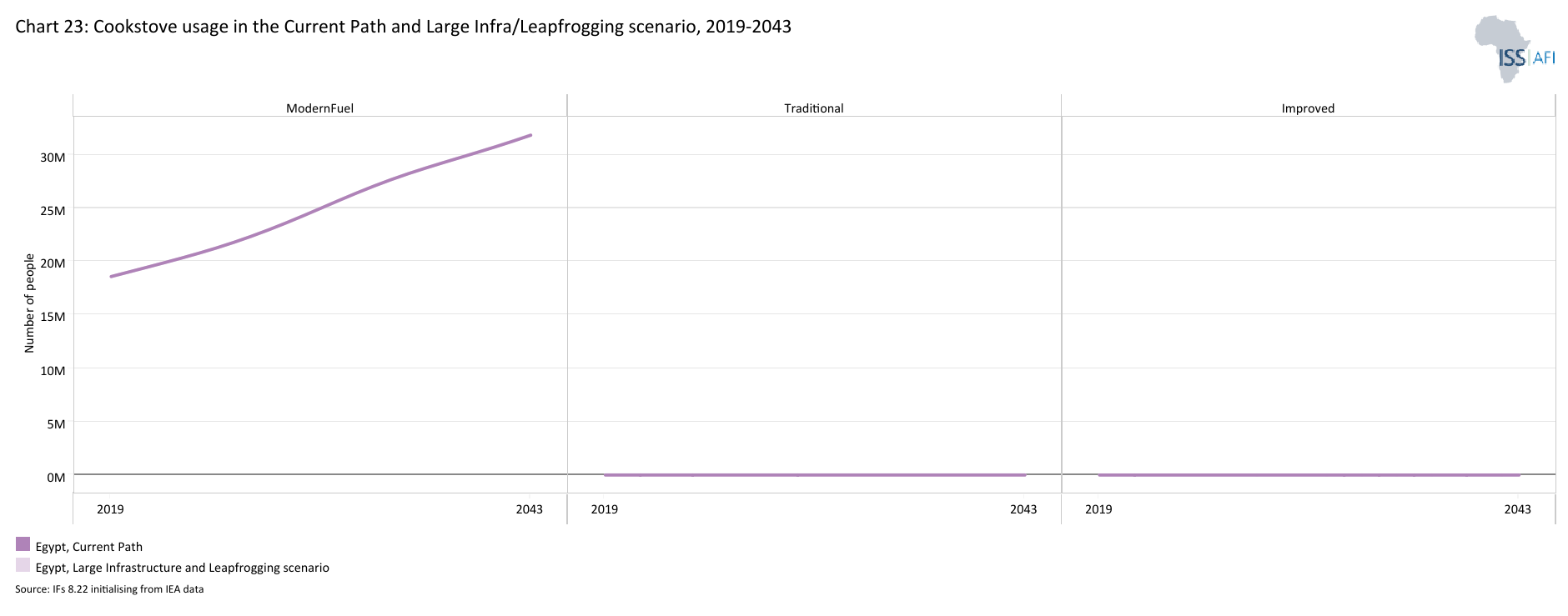

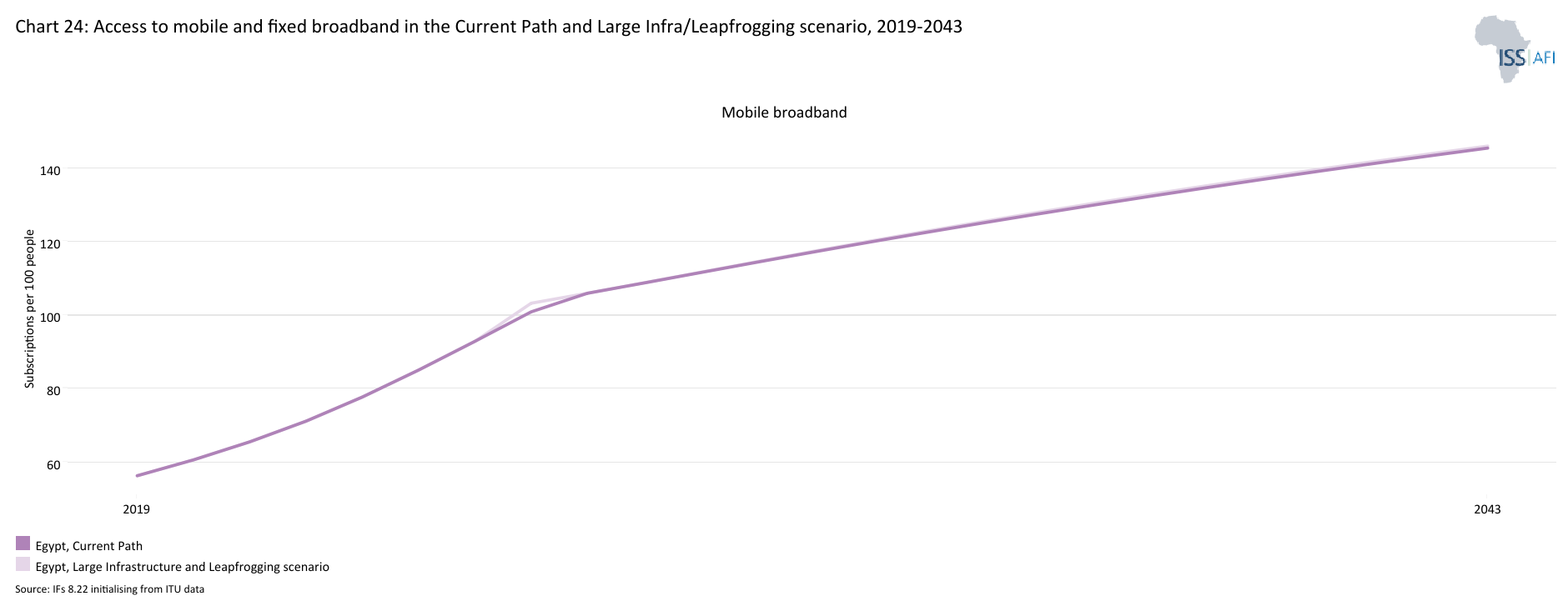

- Due to the universal electricity access rate in Egypt, all households in the country used modern stoves for cooking as of 2023. This trend will continue on the Current Path up to 2043. The Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario will lead to a larger increase in fixed broadband access, so that, by 2043, subscriptions will likely be at 50 per 100 people compared to 33.8 subscriptions on the Current Path.

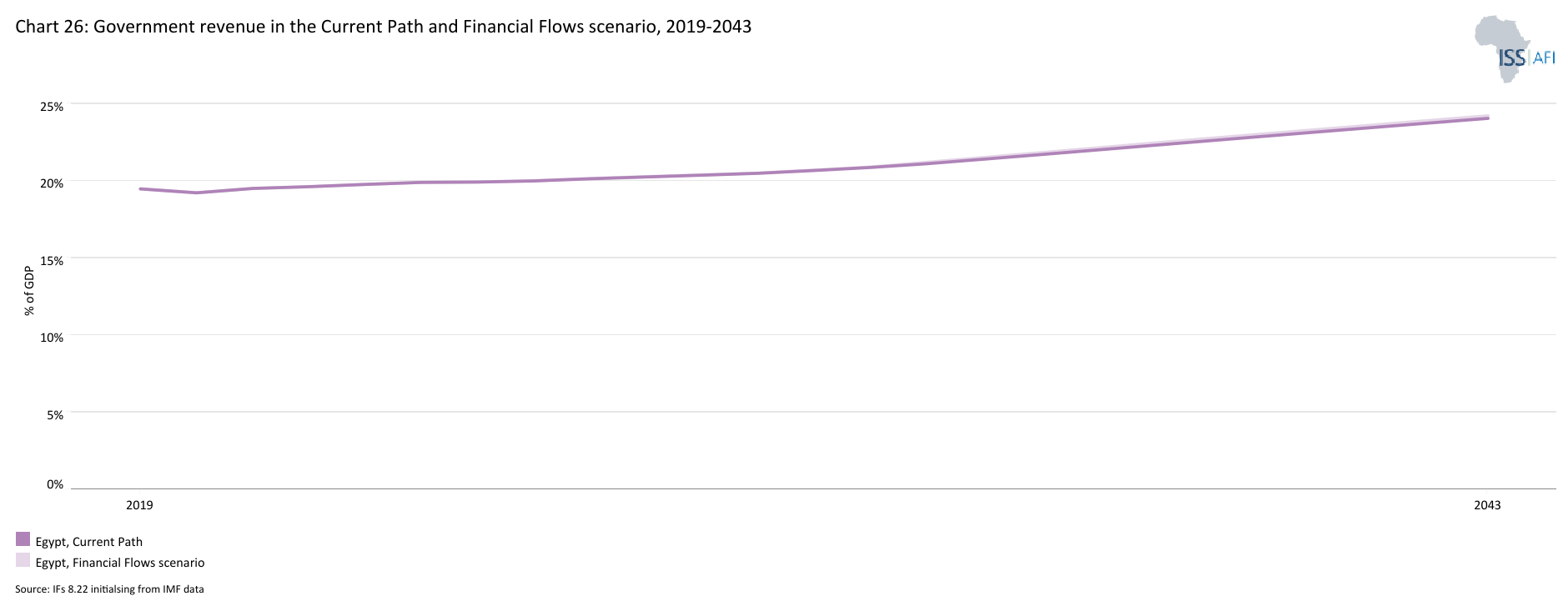

- In 2023, the government’s total revenue amounted to US$64.6 billion, equivalent to 19.7% of GDP — higher than the average of its income-group peers in Africa. Government revenue will increase to US$210.0 billion in 2043, representing 24% of GDP above the average of 21.6% for lower-middle-income countries in the Financial Flows scenario. Compared to the Current Path, the Financial Flows scenario will improve government revenue in Egypt by an additional US$11.3 billion by 2043.

- In comparing governance across three dimensions, Egypt has significantly more security and capacity than lower-middle-income countries but much less inclusion. As a result Egypt’s score on the composite governance index of 0.48 in 2023 was 5.6% lower than the average for its income peers in Africa. In the Governance scenario, Egypt's score on the composite governance index will improve to 0.60, which is about 12% above the Current Path by 2043 and about 7.4% above the Current Path average of lower-middle-income Africa in the same year. The improvement is largely due to improvements in its score on democracy and gender inclusion which form part of the inclusion index.

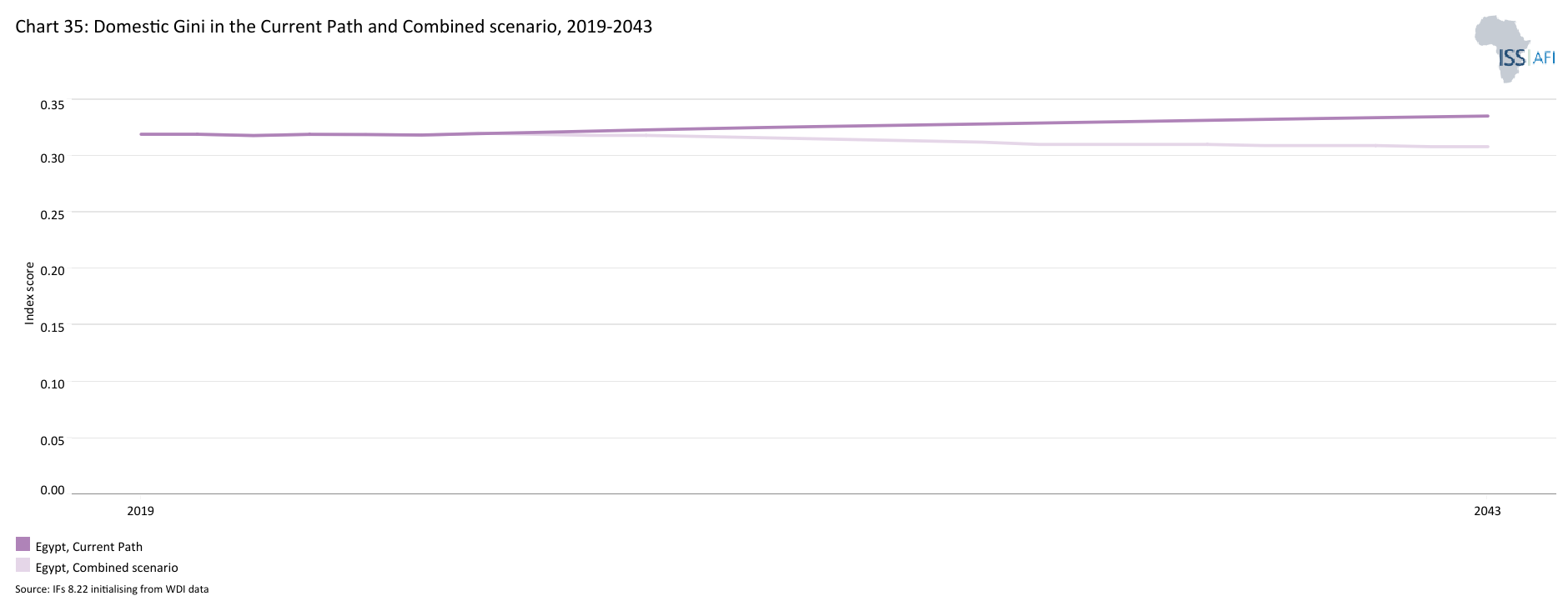

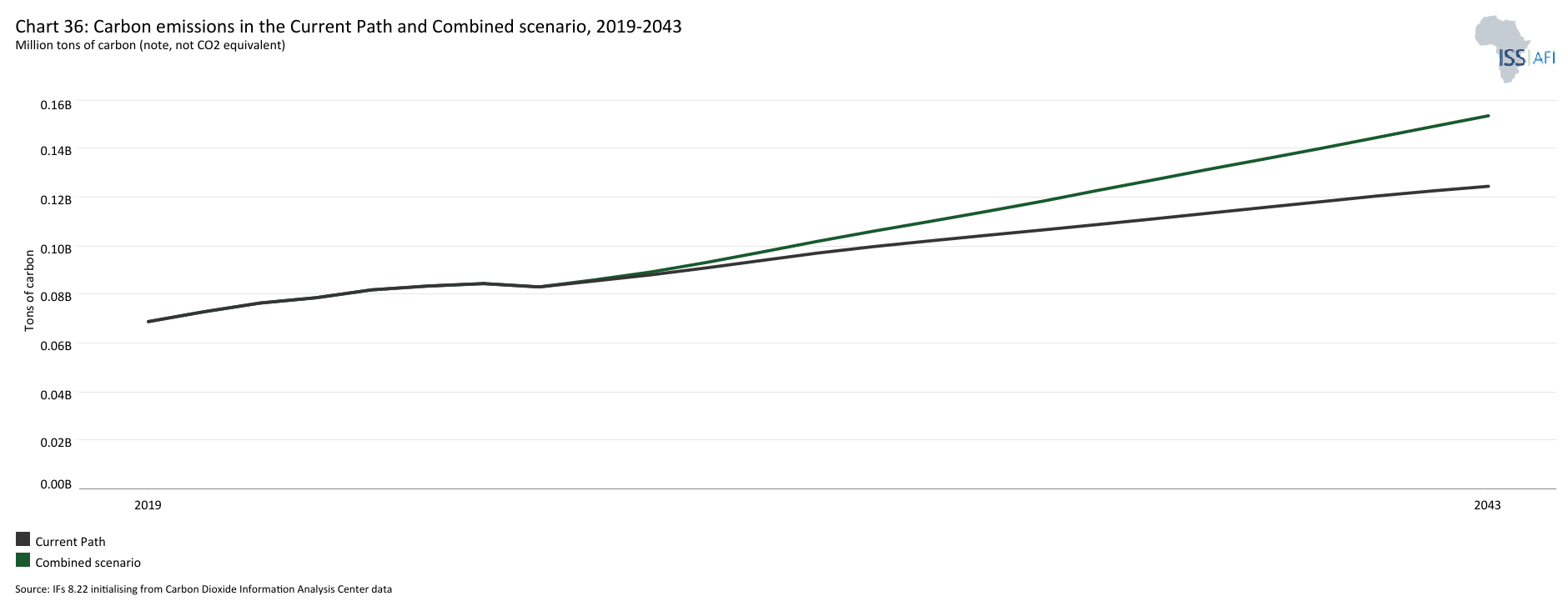

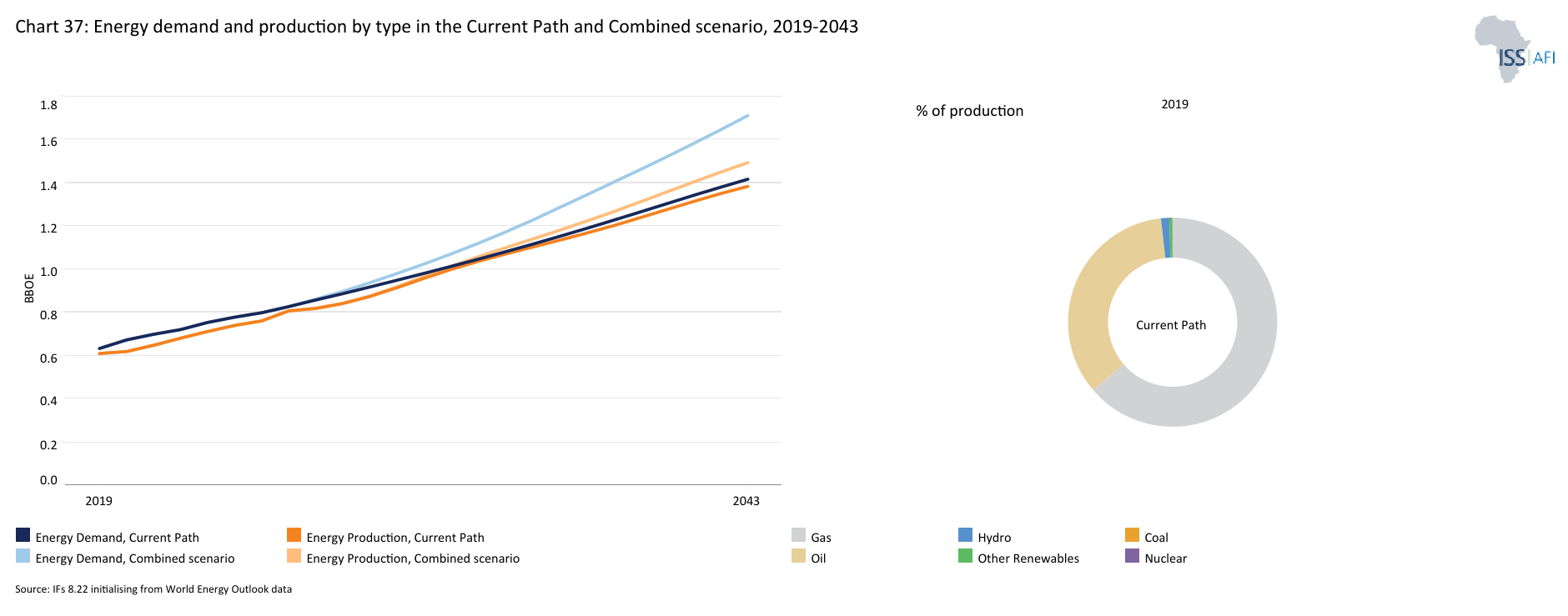

In the third section, we compare the impact of each of these eight sectoral scenarios with one another and subsequently with a Combined scenario (the integrated effect of all eight scenarios). In our forecasts, we measure progress on various dimensions such as economic size (in market exchange rates), gross domestic product per capita (in purchasing power parity), extreme poverty, carbon emissions, the changes in the structure of the economy, and selected sectoral dimensions such as progress with mean years of education, life expectancy, the Gini coefficient or reductions in mortality rates.

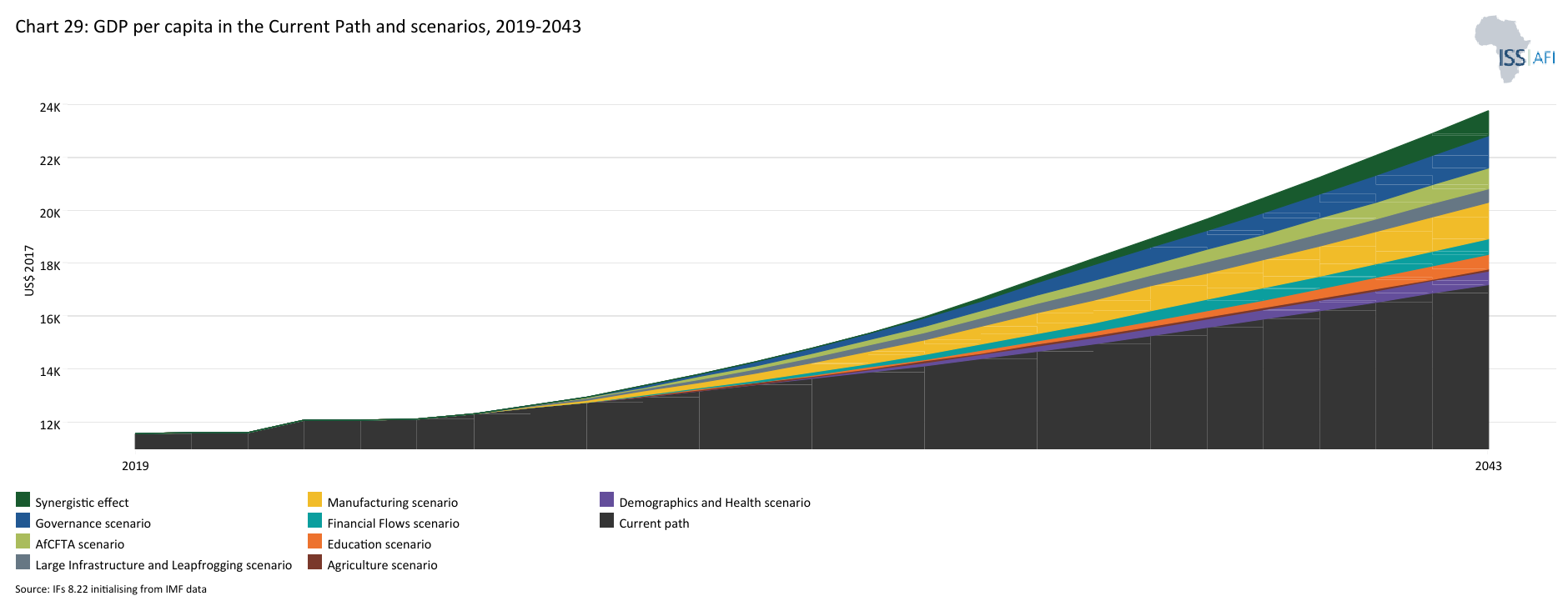

- The scenario with the greatest impact on GDP per capita in Egypt by 2043 is the Manufacturing scenario, followed by the Governance and the AfCFTA scenarios. In the Manufacturing scenario, Egypt’s GDP per capita will witness an increase of US$1 390 or 8.1% more than the Current Path. The Governance and AfCFTA scenarios further raise GDP per capita for Egypt by an additional US$1 250 and US$780 by 2043.

- The Manufacturing scenario also has the largest potential to reduce extreme poverty, followed by the Governance and Education scenarios. The Manufacturing scenario has the potential to reduce extreme poverty in Egypt by an additional 4.8 million people. Similarly, the Education and Governance scenarios can lift about 2.3 and 1.8 million people out of extreme poverty respectively.

- In the Combined scenario, Egypt’s GDP will rise to US$1.3 trillion. This will exceed the Current Path of US$825.7 billion. Similarly, in the Combined scenario, GDP per capita for Egypt will increase to US$23 760 by 2043. This will be US$6 570 more than the projection of US$17 190 on the Current Path.

- By 2043, the service sector will still be the largest contributor to GDP at 53.6%. The manufacturing sector will be the second largest contributor to GDP in the scenario by 2043 with a share of 27.5%. The share of the agriculture sector will decline to 4.9% while the share of ICT will rise 8.3%.

- In the Combined scenario, both the number and portion of poor people will significantly decline. By 2043, only about 2% of Egyptians equivalent to 2.9 million people will be living in extreme poverty, meaning 9.7 million more people could be lifted out of poverty.

- In 2023, Egypt released about 82 million tons of carbon from fossil fuel use. In the Combined scenario, Egypt’s total carbon emissions will rise to 154 million tons — 23.2% higher than what is estimated in the Current Path in the same year.

- The Combined scenario shows an increase in energy demand, creating a larger energy deficit, with renewable energy becoming the dominant energy source, surpassing oil and gas. By 2043, the excess demand for energy in the scenario of 219 million BOE will be more than 6 times than the Current Path. In the Combined Scenario, gas production will still constitute 79.4% of total production followed by other renewable energy (11.8%) and oil (8.2%) of total production

We end this page with a summarising conclusion offering key recommendations for decision-making.

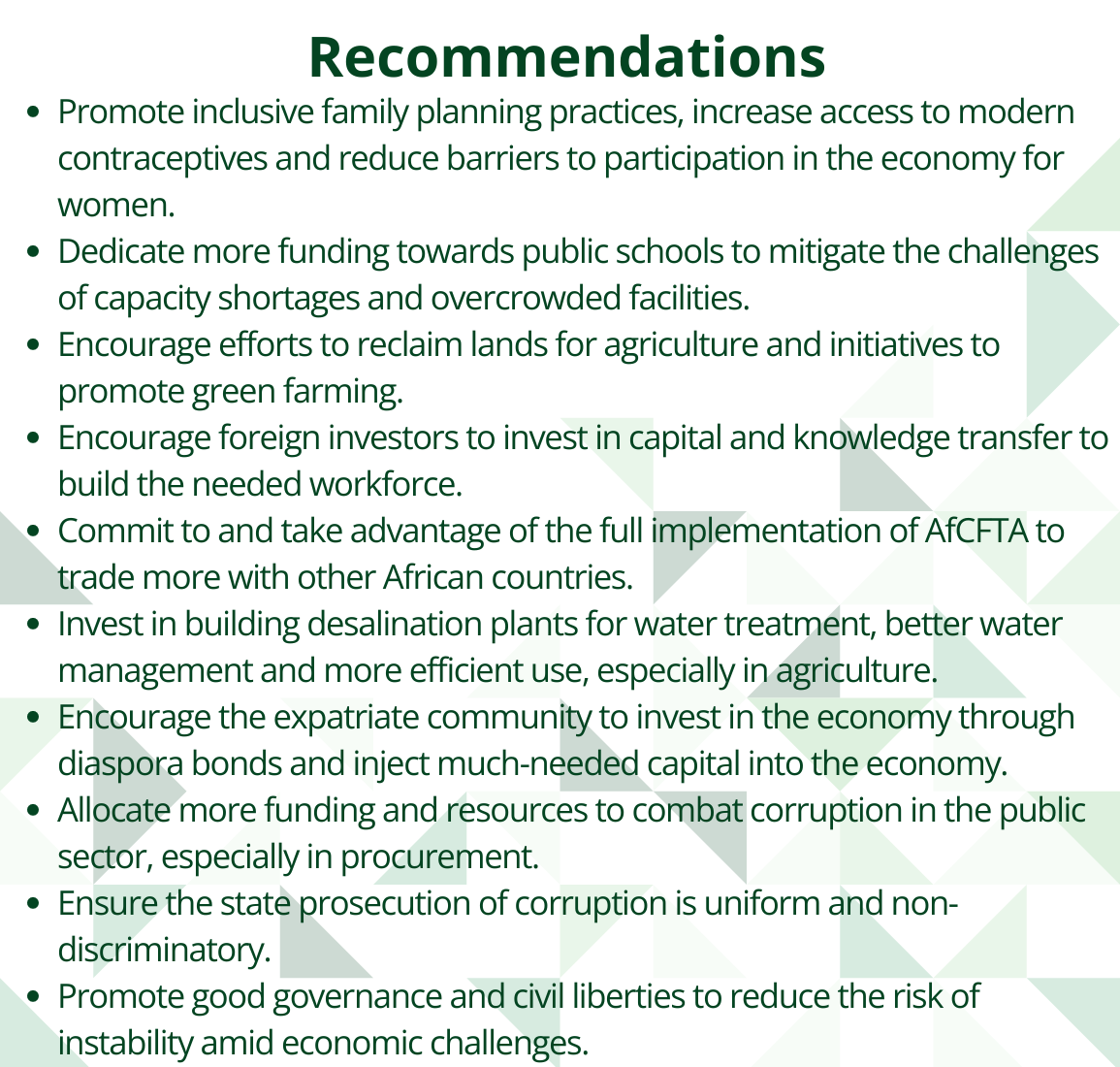

Egypt has made significant progress in advancing human development and its economic growth prospect is higher than its African income peers. However, it will still lag behind its Vision 2030 targets if it does not accelerate its development potential and harness its manifold economic opportunities. Therefore, a comprehensive and targeted set of socio-economic policy interventions across demographics, health, education, agriculture, infrastructure, manufacturing, trade, financial flows and governance is necessary to redirect the country’s current development trajectory towards a more sustainable and inclusive path.

All charts for Egypt

- Chart 1: Political map of Egypt

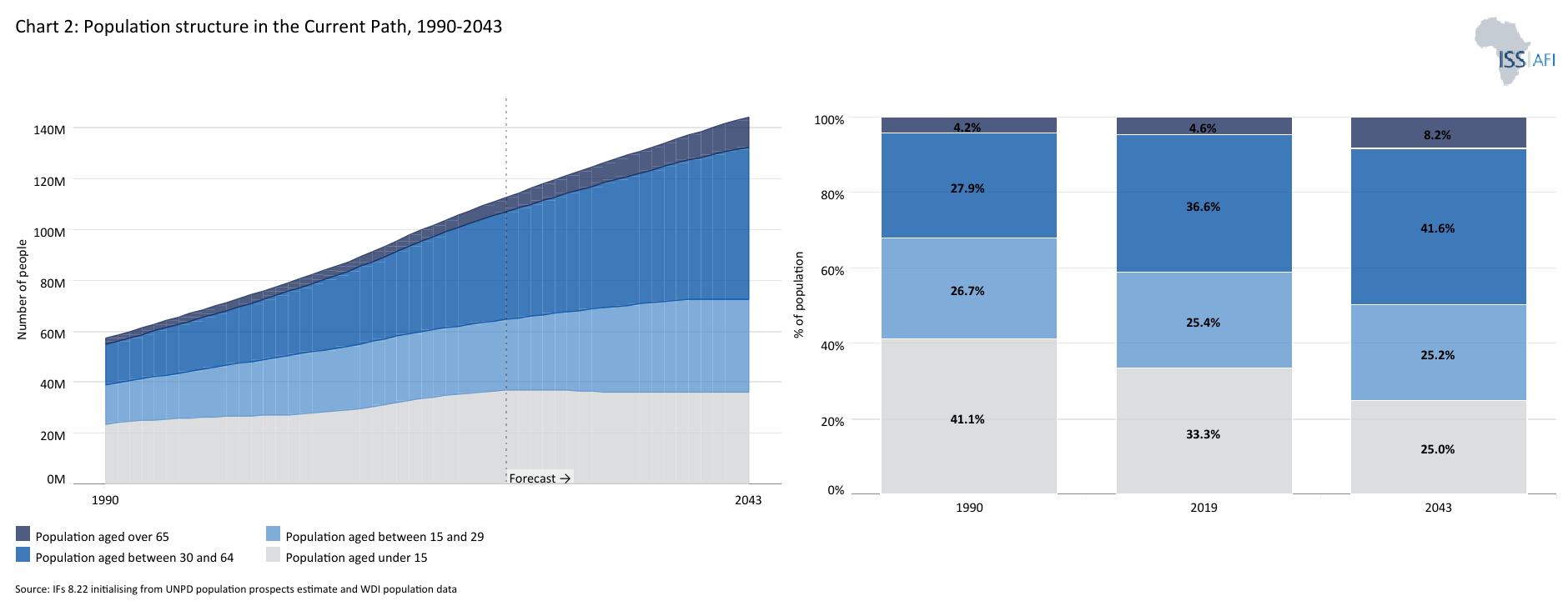

- Chart 2: Population structure in the Current Path, 1990–2043

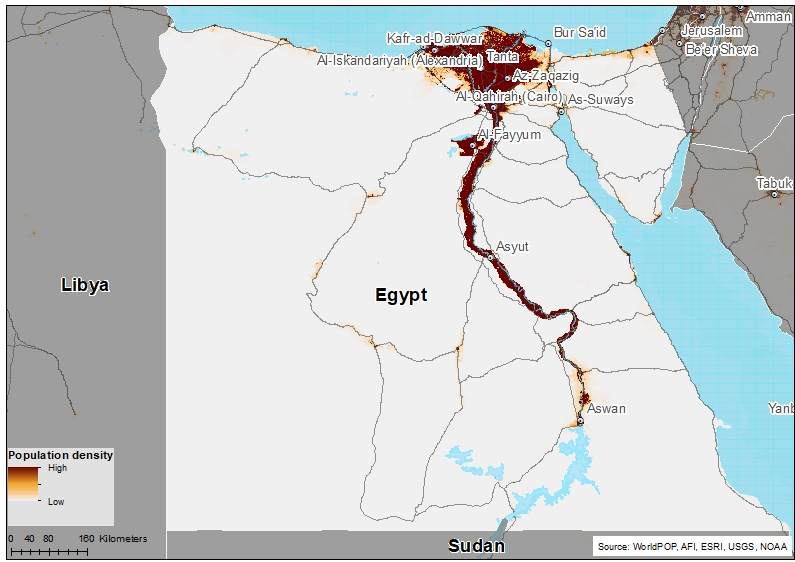

- Chart 3: Population distribution map, 2023

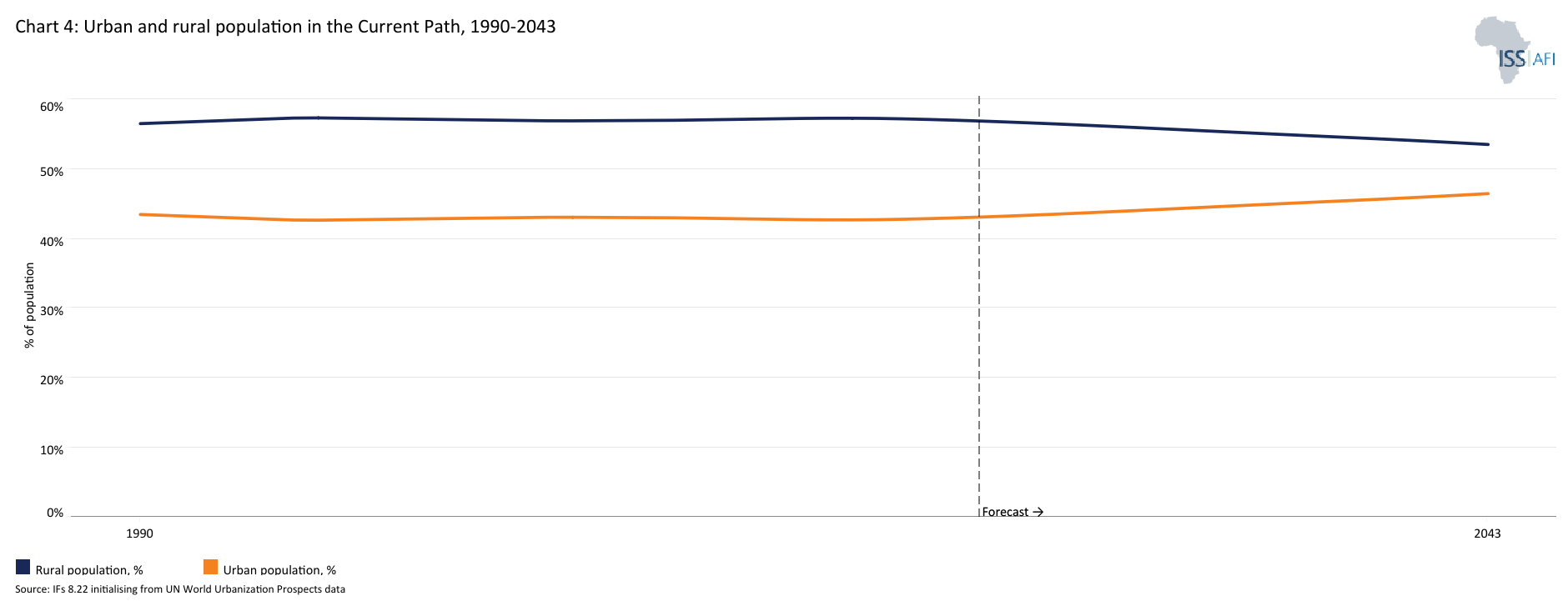

- Chart 4: Urban and rural population in the Current Path, 1990-2043

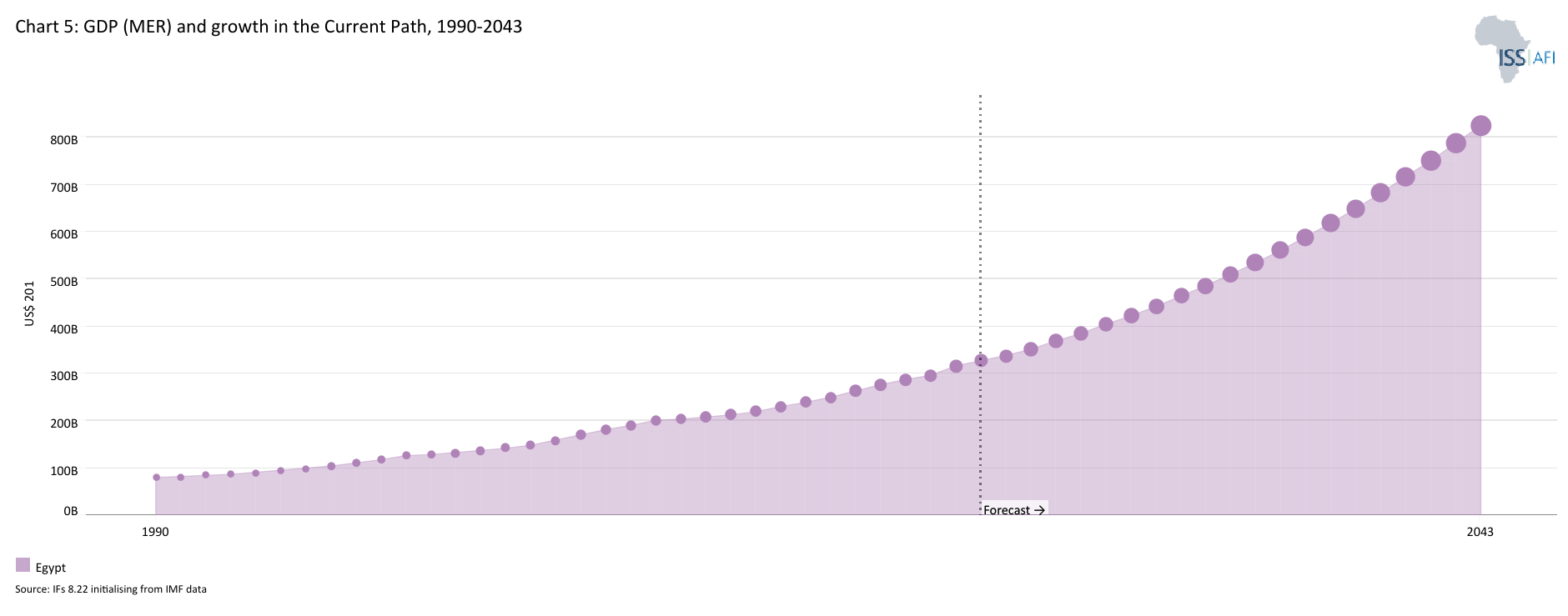

- Chart 5: GDP (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, 1990–2043

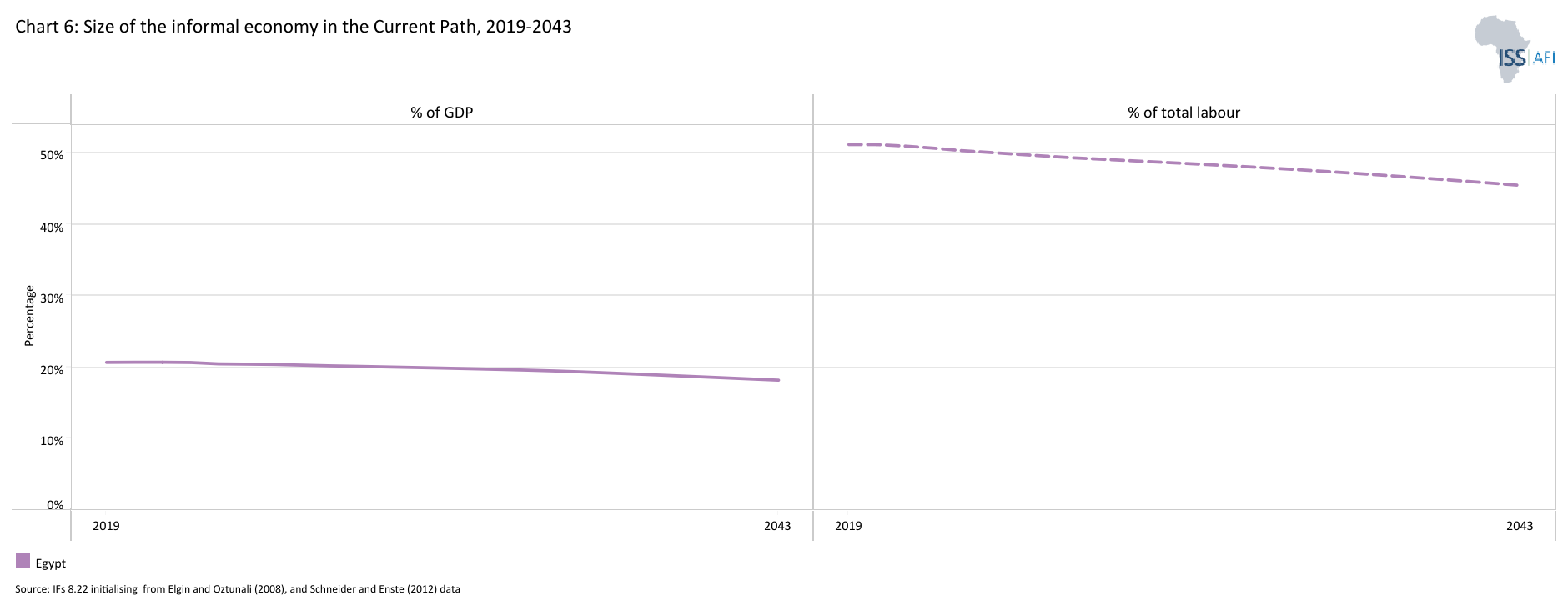

- Chart 6: Size of the informal economy in the Current Path, 2019-2043

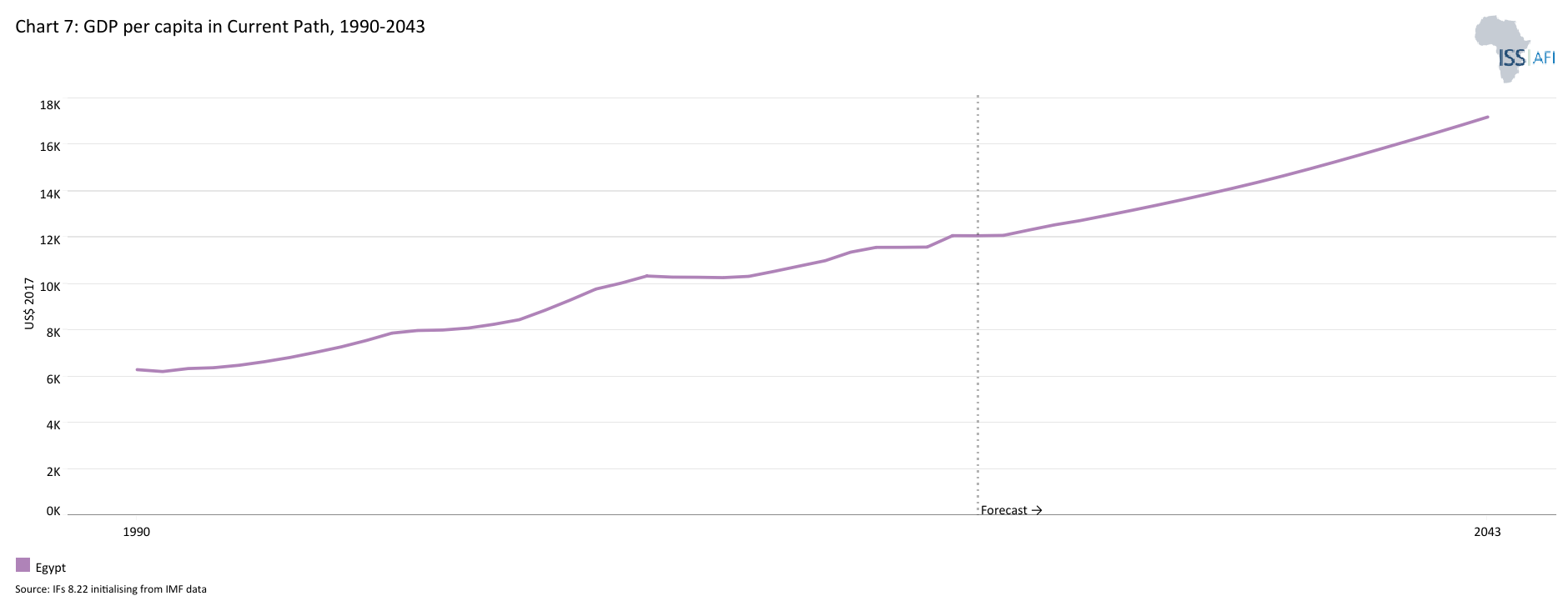

- Chart 7: GDP per capita in Current Path, 1990–2043

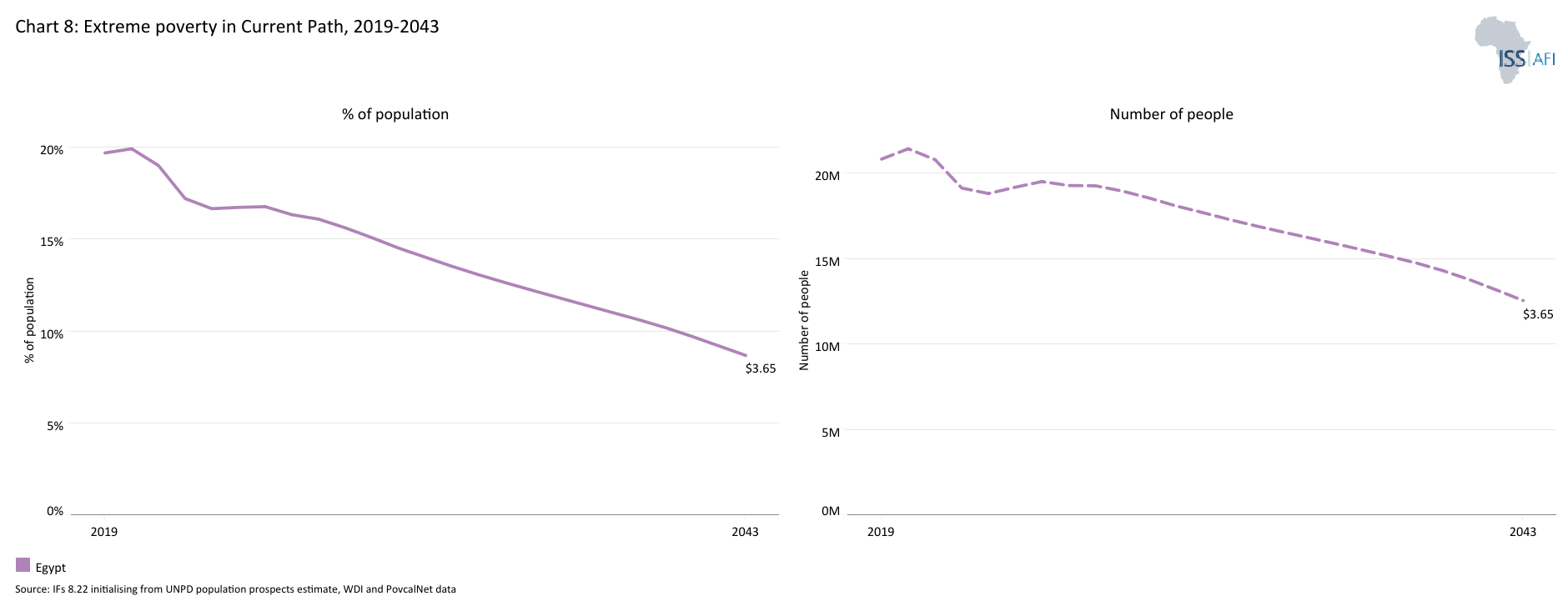

- Chart 8: Extreme poverty in the Current Path, 2019–2043

- Chart 9: National Development Plan of Egypt

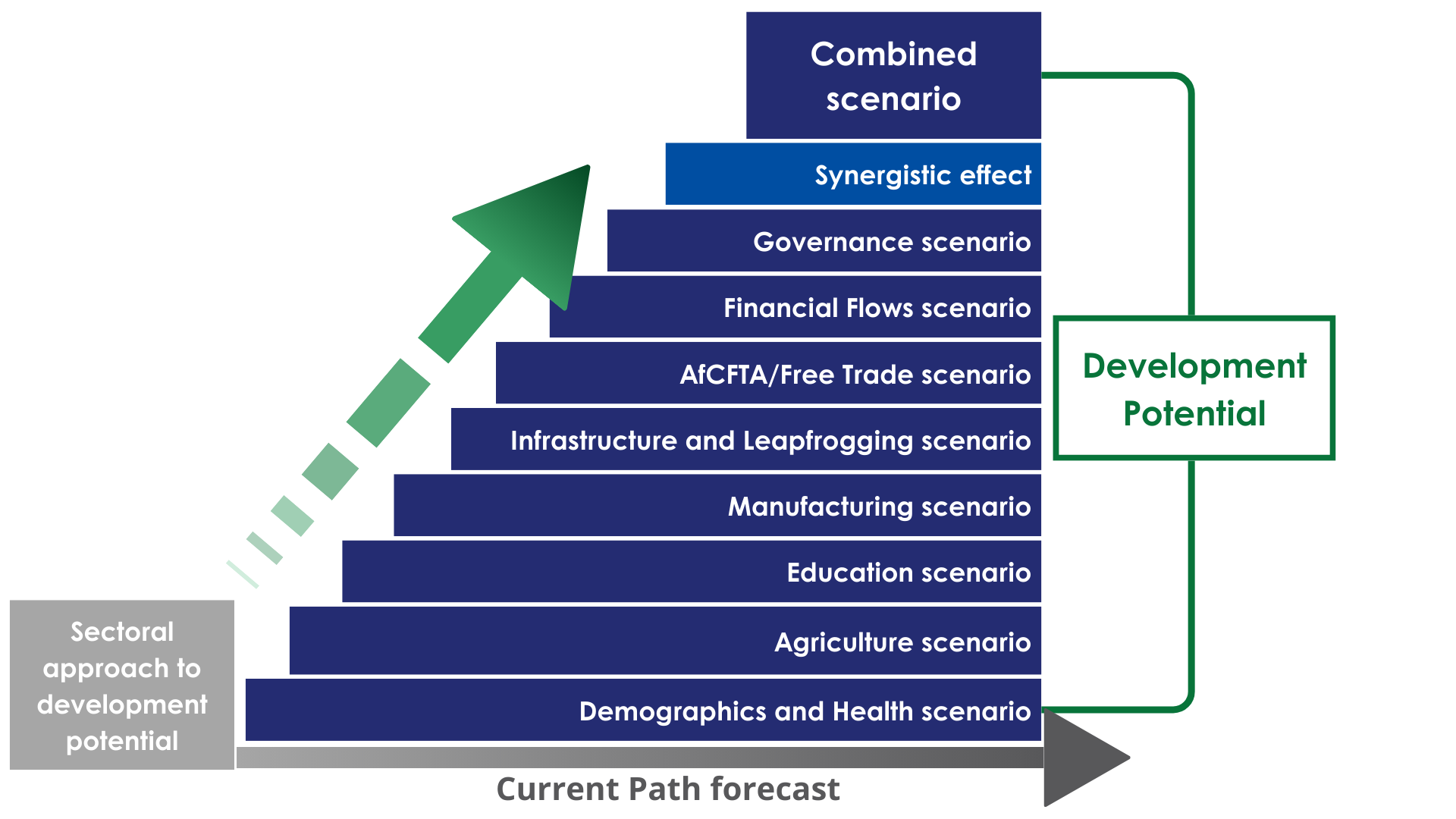

- Chart 10: Relationship between Current Path and scenarios

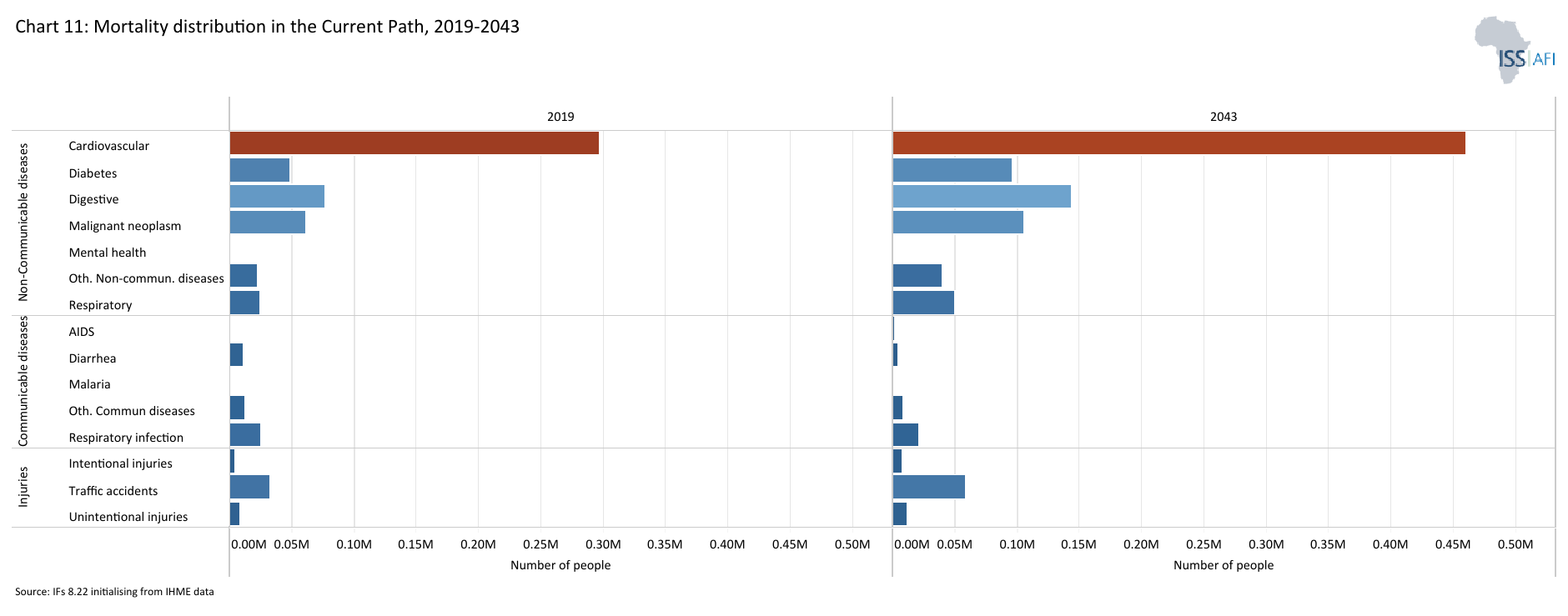

- Chart 11: Mortality distribution in the Current Path, 2019-2043

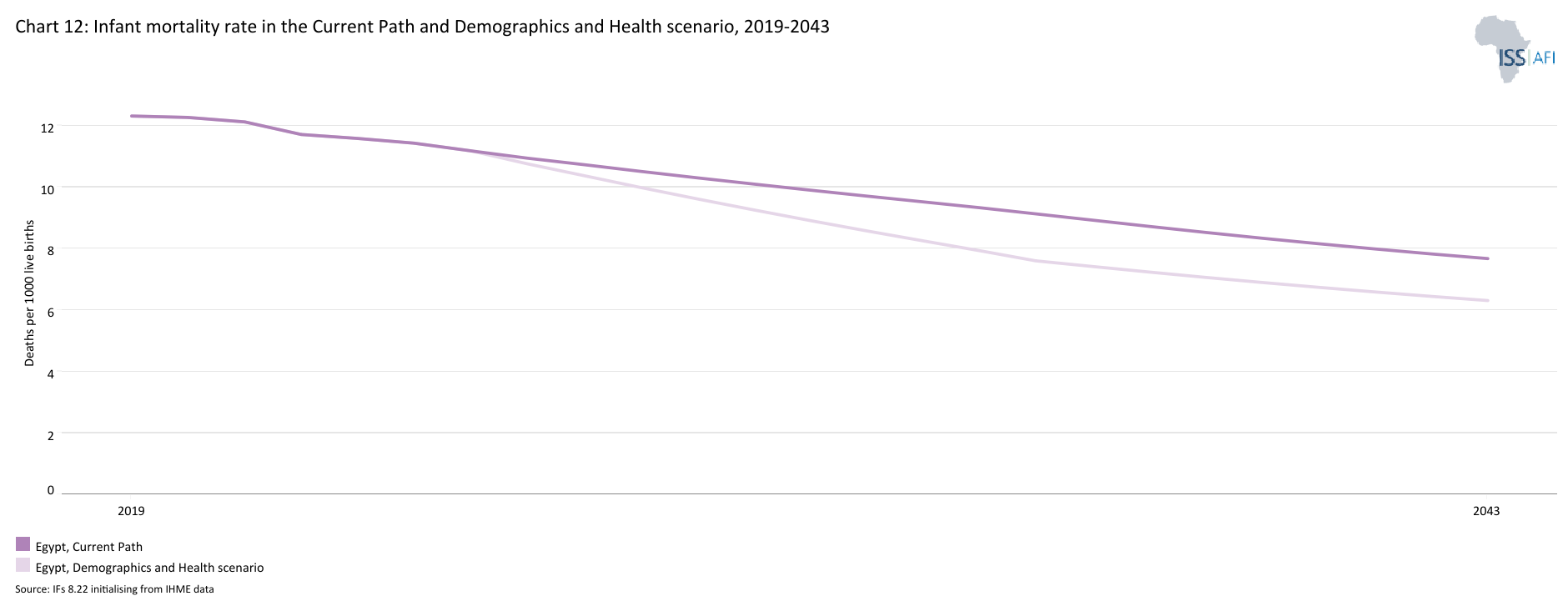

- Chart 12: Infant mortality rate in Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 2019–2043

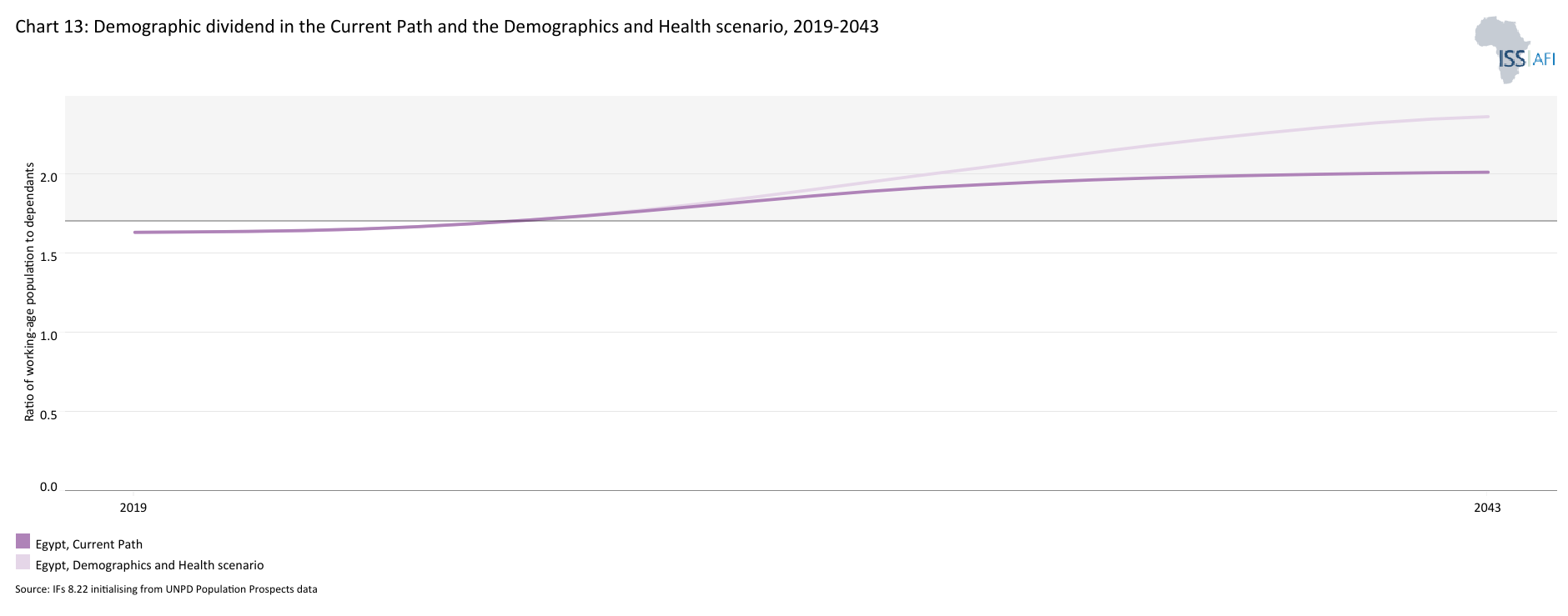

- Chart 13: Demographic dividend in the Current Path and the Demographics and Health scenario, 2019–2043

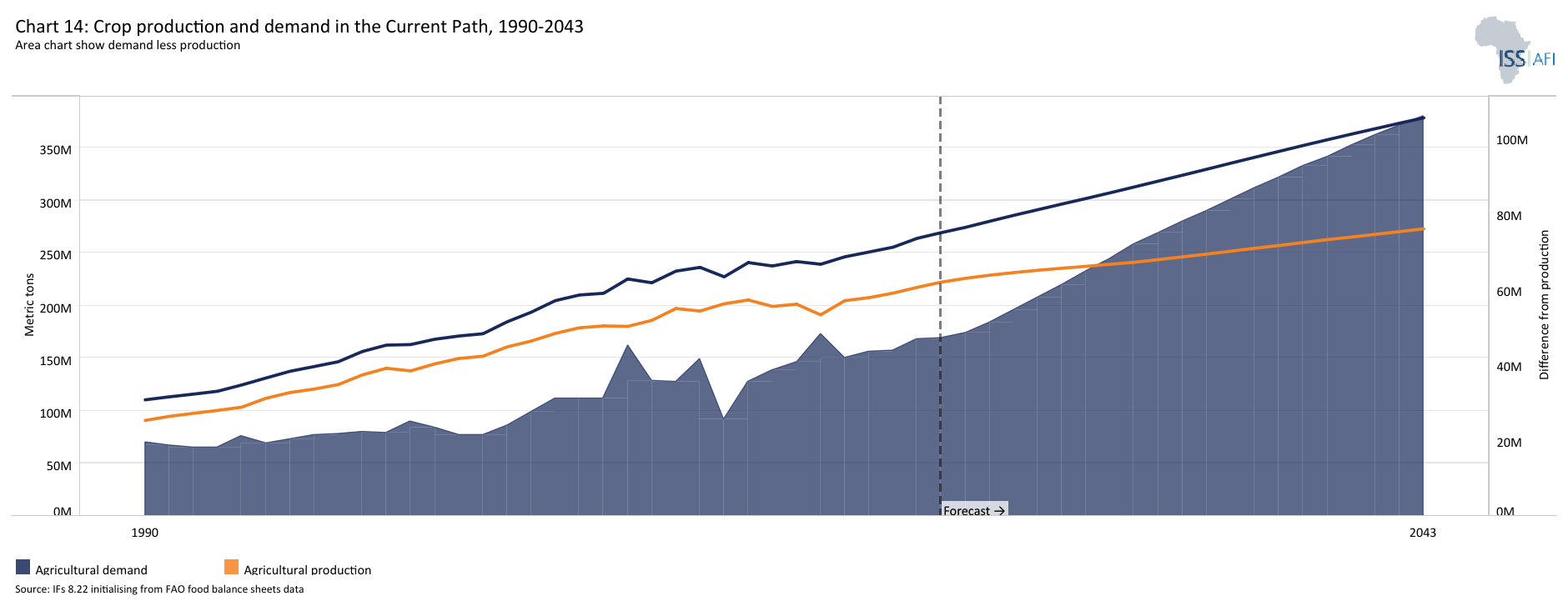

- Chart 14: Crop production and demand in the Current Path, 1990-2043

- Chart 15: Import dependence in the Current Path and Agriculture scenario, 2019–2043

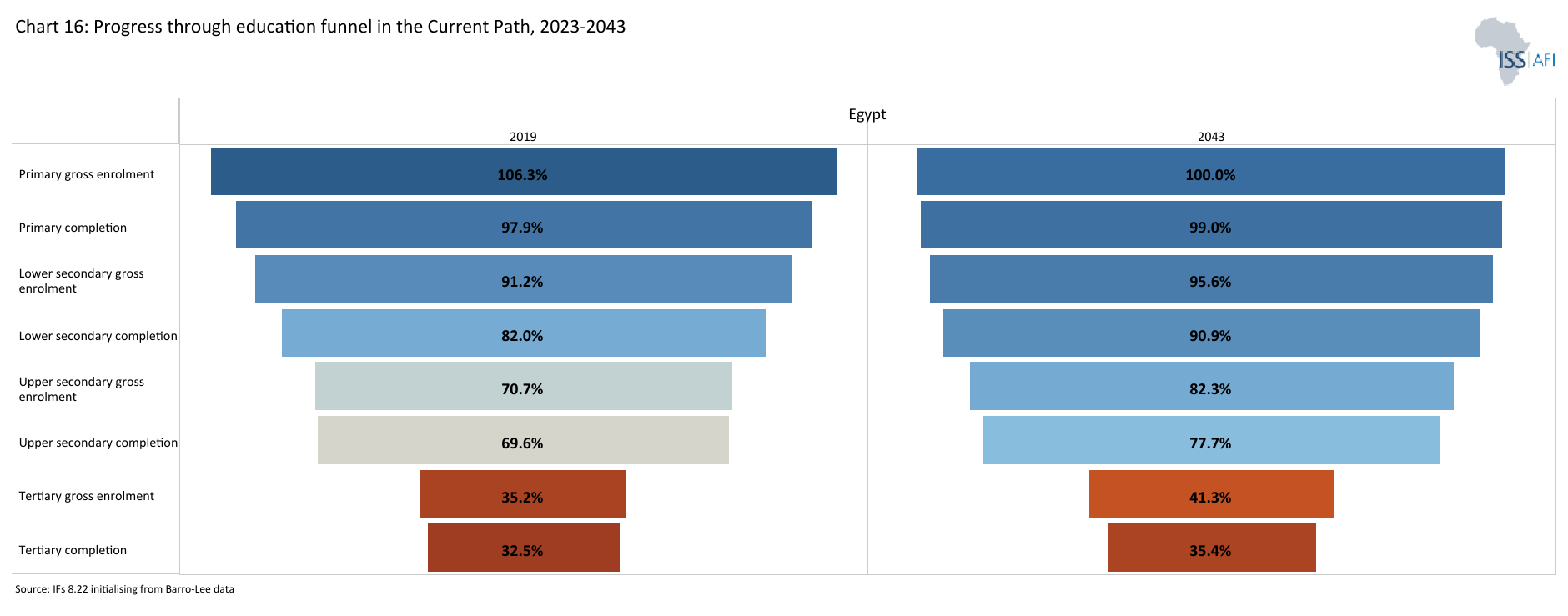

- Chart 16: Progress through education funnel in the Current Path, 2019-2043

- Chart 17: Mean years of education in the Current Path and Education scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 18: Value-add by sector as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2019-2043

- Chart 19: Value-add by the manufacturing sector in the Current Path and Manufacturing scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 20: Exports and imports as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2000-2043

- Chart 21: Trade balance in the Current Path and AfCFTA scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 22: Electricity access: urban, rural and total in the Current Path, 2000-2043

- Chart 23: Cookstove usage in the Current Path and Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 24: Access to mobile and fixed broadband in the Current Path and the Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

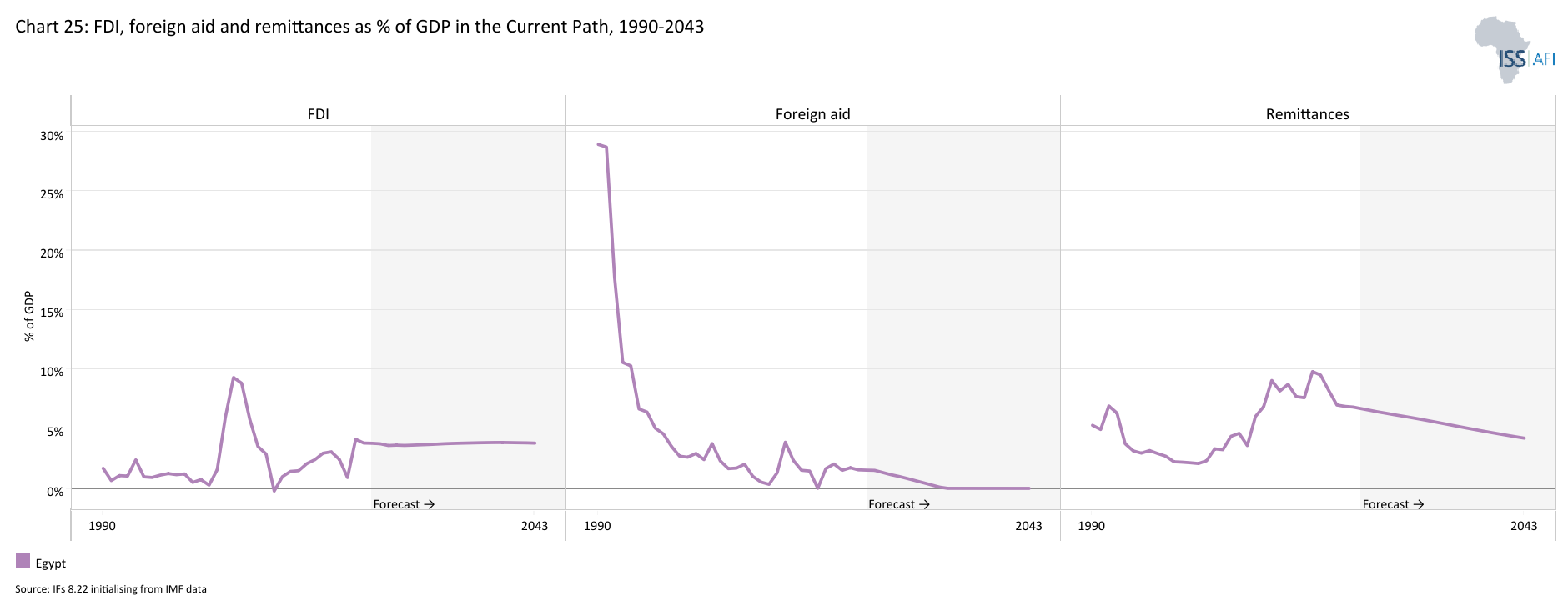

- Chart 25: FDI, foreign aid and remittances as % of GDP in the Current Path, 1990-2043

- Chart 26: Government revenue in the Current Path and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

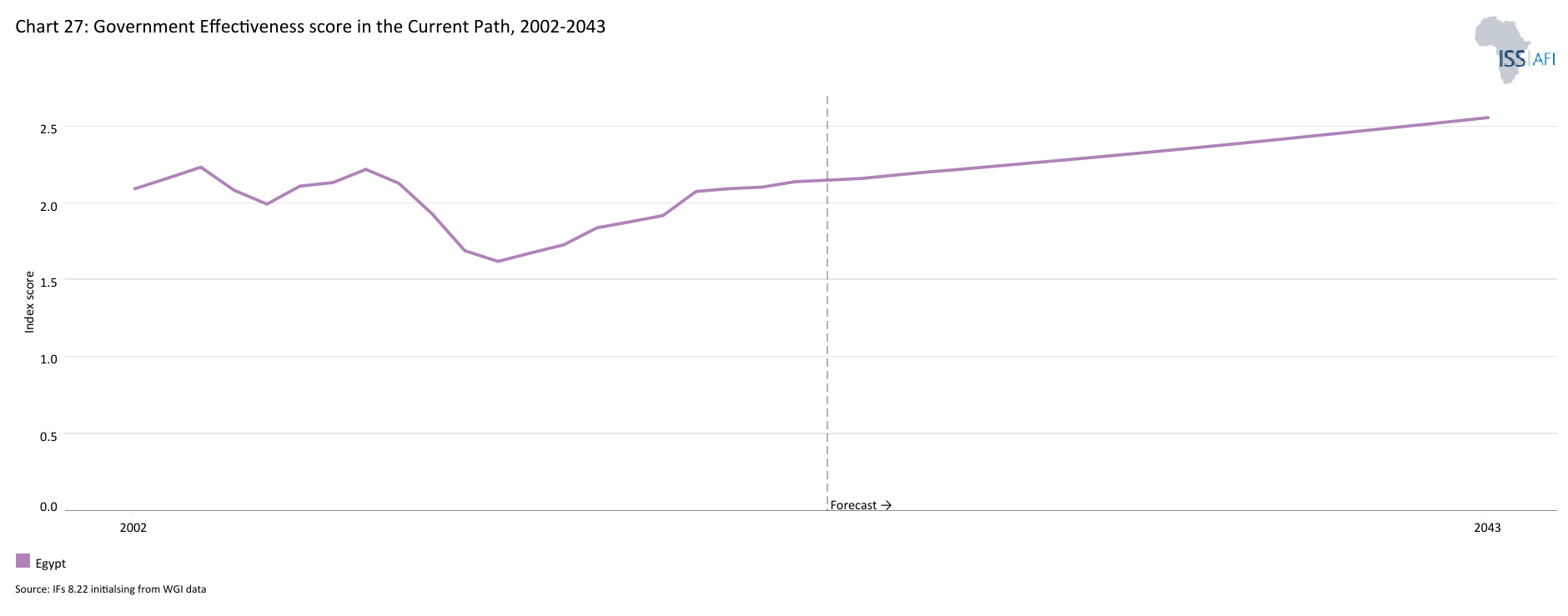

- Chart 27: Government effectiveness score in the Current Path, 2002-2043

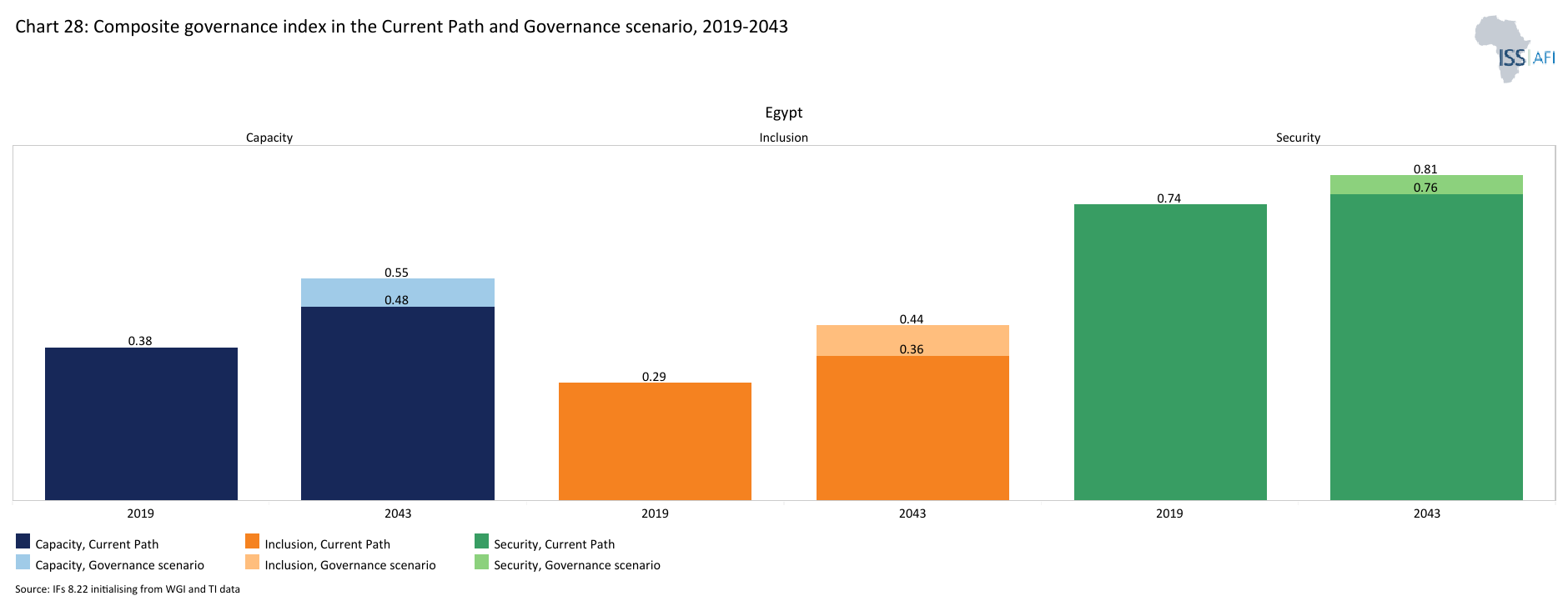

- Chart 28: Composite governance index in the Current Path and Governance scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 29: GDP per capita in the Current Path and scenarios, 2019–2043

- Chart 30: Poverty in the Current Path and scenarios, 2019–2043

- Chart 31: GDP (MER) in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 32: Value added by sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 33: Informal sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

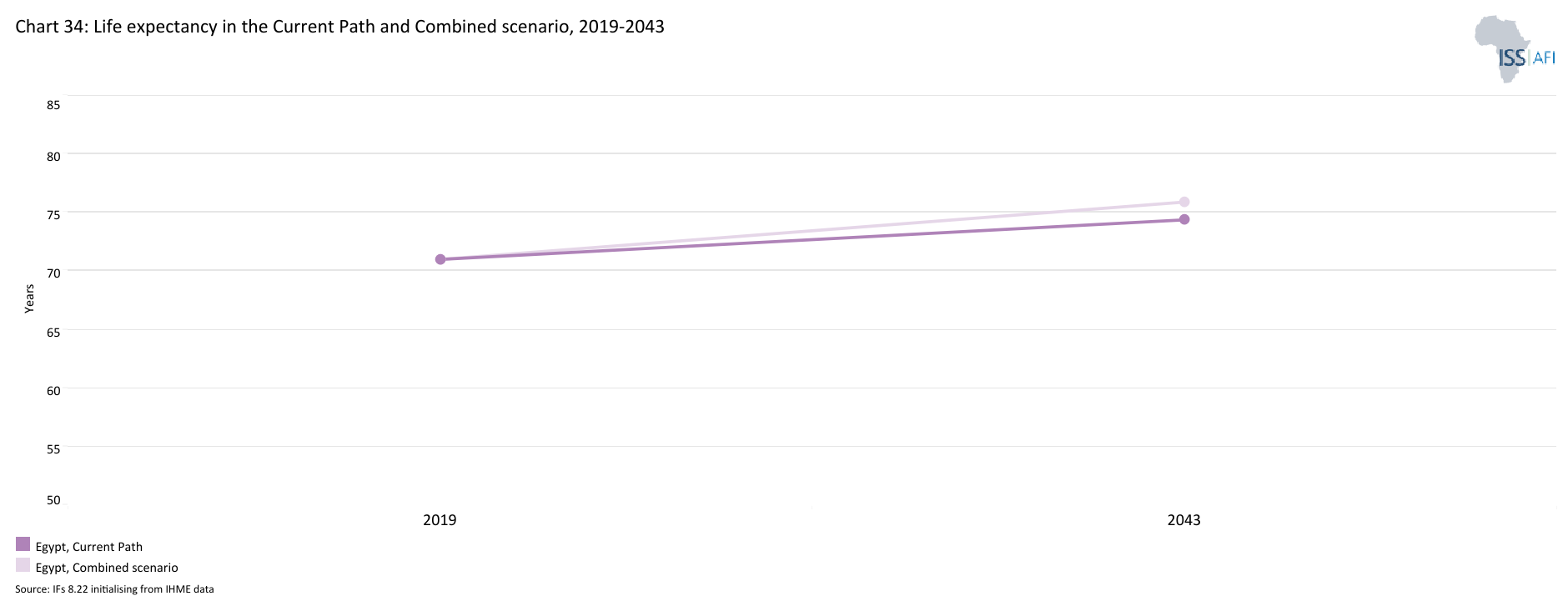

- Chart 34: Life expectancy in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 35: Domestic Gini in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 36: Carbon emissions in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 37: Energy demand and production by type in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019-2043

- Chart 38: Policy recommendations

Chart 1 is a political map of Egypt.

Egypt is one of the 24 lower-middle-income countries in Africa, it is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and the southwest corner of Asia. It is bordered by Israel, including the Gaza Strip after its occupation by Israel in 1967, Sudan and Libya, as well as the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. With a rich legacy, and often referred to as the “cradle of civilisation”, the nation thrives on tourism from all over the world, and has a population of over 113 million people as of 2023. Its official language is Arabic.

Egypt is considered a regional power in Africa and the Middle East. Geographically, it is the world’s 30th-largest country in terms of land mass, but 99% of the population makes use of only 5.5% of the land (along the Nile river), yielding one of the most densely-populated countries in Africa. Its landscape is mostly desert with some oases, with averagely very little rainfall, and a hot, sunny and dry climate. Its largest cities include Cairo, the capital, Alexandria and Giza, all popular tourist cities.

General Gamal Abdel Nasser assumed Egypt's presidency in 1954 following the 1952 revolution until he died in 1970, when he was succeeded by Anwar Sadat who was assassinated in 1981. The assassination of President Sadat paved the way for Hosni Mubarak to assume Egypt's Presidency, who ruled the country until his resignation in February 2011 following the Arab Spring that had started in Tunisia in 2010. In Egypt, the Arab Spring was characterised by massive street protests against President Mubarak for allegations of corruption, poor governance, poverty and political oppression, among others. After the resignation of President Mubarak, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces suspended the Constitution, dissolved the People’s Assembly and constituted a transitional body to supervise the country's democratisation process.

The transitional process continued until June 2012, when Mohamed Morsi was declared president. However, his regime came to an abrupt end in the wake of massive protests in June 2013 calling for his immediate resignation, by people disgruntled by the direction in which Egypt was heading. The subsequent military intervention following the popular uprising sought to rectify the course of Egypt's democratic transition after being hijacked by Islamist groups. In May 2014, another election was held in which President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi was declared the winner. His leadership has reduced the social turbulence that characterised the last decade. In 2018, President Al-sisi won a second term with 97% of the vote. A 2019 constitutional amendment extended the tenure of office of the president to six years though it maintained the term two-term limit. However, provisions were made to allow President Sisi to run for a third six-year term. The December 2023 election saw President Sisi win 89.6% of total votes to secure another six-year tenure.

Administratively, Egypt is divided into 27 governorates though power is still highly centralised. The President appoints governors and other executive officials. Thus, decentralisation is limited to administrative functions without devolution of substantive authority powers.

Approximately 90% of the population is Sunni Muslim and 10% is Christian. Shia Muslims comprise approximately 1% of the population.

Egypt has suffered from terrorism for decades, with attacks targeting government officials, security forces, tourists, religious minorities and civilians. The main perpetrators are Islamic extremist groups, prominently the Ansar Beit Magdis in Sinai, however recent developments suggest that Egypt has succeeded in defeating these terrorist groups. After the 1973 war with Israel, Egypt has not been at war with others, but has sought to protect itself from terrorism.

Chart 2 presents the Current Path of the population structure, from 2090 to 2043.

Egypt is the most populous country in North Africa, and the 3rd most populous country in Africa after Nigeria and Ethiopia. In 1990, Egypt’s population stood at 57.2 million people. By 2023, the population had nearly doubled to 113 million people. This growth can be attributed to the high fertility rate in many parts of the country, particularly in the rural areas where fertility rates are far above the national average. A study by the United Nations (UN) Population Fund in 2018 found that fertility rates reached 2.75 in urban governorates, compared to 3.52 to 3.93 for both Upper Egypt and border governorates, respectively. Also, there is also a high proportion of women within their childbearing age coupled with low usage of modern contraceptives mainly due to socio-economic factors. These include the perception that more than three children are ideal, lack of female empowerment with husbands still being the main decision makers and disapproving of family planning, and inadequate labour market opportunities for women. Rapid population growth as a result of high fertility rates and population momentum have costly repercussions for the economy and human development prospects. It inevitably contributes to the deterioration of quality of life in terms of health, nutrition, access to employment and other basic amenities.

However, population growth has slowed in recent years due to the slowing fertility rate. In 2023, Egypt’s population growth rate of 1.5% made it the 10th-lowest in Africa. This was below the average of 2.6% for Africa and a decline from the 2.2% it recorded in 1990. Likewise, in 2023, the total fertility rate among women in the childbearing age in Egypt of 2.8 births per woman was below Africa’s average of 4.3 births per woman and was the 11th-lowest in Africa and the 4th-lowest in North Africa after Tunisia, Morocco and Libya. In terms of population structure, 32.6% of Egyptians were below the age of 15 years while 62.3% were in the age group 15–64 years (working age) and 5% were 65 years and older. Comparing this with the structure in 1990 reveals that Egypt’s population structure has fundamentally changed over the past three decades.

The country’s youth bulge (the ratio of its population aged between 15 and 29 to the total adult population) stood at about 37% in 2023 — a fall from 45% in 1990. This was below the average of 45.4% for Africa but higher than the 33.9% average for North Africa. The median age for Egypt in 2023 was 25.3 years — an increase from 18.4 years recorded in 1990 and Africa’s median age of 20.4 years but below North Africa’s average of 27.4 years. The large youth bulge in the country raises concerns about youth unemployment and underemployment. The IMF projection in 2019 was that the country needs to create about 3.5 million jobs over the next 5 years to benefit from its demographic dividend.

In the forecast horizon, the structure of the Egyptian population will change as the share of the youth population declines. With the country’s population growth rate declining to 0.9% by 2043, the total population will rise modestly reaching 145.4 million in 2043 by which it will be the fourth-largest in Africa after Nigeria, Ethiopia and DRC. By then, the median age will increase to 30.0 years, and the youth bulge will slightly fall to 33.6%. The proportion of people under the age of 15 will decline to 25%, while the share of the working-age population and the population aged 65 and older will increase to 66.8% and 8.2%, respectively, by 2043. Such rapid decline in population growth will follow the rise in the use of modern contraceptives in the country reaching 74% of fertile women. This can facilitate Egypt’s development and improve average incomes much quicker as the demands on the fiscus to cater to its youthful population will reduce.

Chart 3 presents a population distribution map for 2023.

The total land area of Egypt is approximately 101 million km². In 2023, Egypt was the most densely populated country in North Africa and the 16th most densely populated country in Africa. The population density of Egypt is estimated to be about 1.14 people per hectare, which is higher than the average of 0.49 for Africa and 0.32 for Northern Africa. The majority of Egyptians reside in the rural areas along the fertile soils of the Nile valley and in the urban clusters of Cairo and Alexandria. The population density along the Nile is among the highest globally at more than 2 000 people per square kilometre. The most densely populated cities in Egypt include the national capital Cairo, Alexandria, Kalyouble, Gharbia, Suhag, Menoufia and Giza, among others. Other small communities are spread throughout the desert around the oases and historic trade routes.

Chart 4 presents the urban and rural population in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

In 1990, more than half (56.5%) of Egypt’s population resided in rural areas, below the average of 68.5% for Africa and 64.4% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. Contrary to the situation in most other developing countries, the proportion of people in rural areas over the past three decades has generally stagnated. By 2023, 57% of the Egyptians still resided in rural areas compared to 55.2% average for Africa and 48.8% for Africa’s lower-middle-income countries. This signals ruralisation or counter-urbanisation in Egypt while its income peers are urbanising rapidly. The higher rural population can be explained by the fact that the majority of the population is concentrated along the fertile soils of the Nile Valley. Only 13 of Egypt’s cities have a population of more than 300 000 with eleven of them having inhabitants of under 500 000.

Nonetheless, there has been rapid migration into Cairo such that in 2017, about 500 000 additional people moved to settle in the city of Cairo making it the fastest growing city in the world. By 2030, Cairo will have 25 million people. The rapid population and urban expansion will further strain the provision and access to basic services like water and sanitation, especially to the 10 million to 12 million Egyptians living in informal settlements in urban areas. Already, about two-thirds of residents in the Greater Cairo Region reside in informal settlements which are mostly slums, and lack basic social amenities such as water and electricity. As a result, Cairo is considered to be one of the cities under threat globally, especially because Egypt is forecast to experience a critical water shortage by 2025.

To ease the pressure on Cairo, the government has been building a new city to serve as the New Administrative Capital since 2016. Located 30 miles east of Cairo and covering a 270-square-mile area, the new city, when completed, can accommodate almost 6.5 million people. With phase one almost completed, more than 1 500 families have already moved into the new city. Also, many government ministries have moved there with 48 000 government employees working there.

The trend of ruralisation will continue into the future as the proportion of the population that will reside in rural areas will only slightly decline to 53.5%, above the 41.2% average for its income peers meaning that the country will experience a slower rate of urbanisation compared to its income peers.

Chart 5 presents GDP in market exchange rates (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

In 2023, Egypt was the third-largest economy in Africa after Nigeria and South Africa. Its economy depends mainly on agriculture, telecommunication, petroleum exports, natural gas and tourism; it is also home to the Suez Canal, an artificial sea-level waterway which is considered the most important centre of maritime transport in the Middle East. Egypt’s GDP measured in market exchange rates (MER) almost quadrupled from US$79.9 billion in 1990 to US$327.9 billion in 2023. The average GDP growth rate within this period stood at 4.4% per annum, above the average of 3.8% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. Although Egypt’s Vision 2030 targets a GDP growth rate of 10%, this goal was not met as the average growth rate between 2015 to 2020 stood at 4.5%.

The country’s economic liberation began in the 1970s and intensified in the 1980s. Some of the policies implemented included the substitution of expenditure on defence for infrastructural projects, as well as the shoring up of the natural gas industry, and the liberalisation of foreign trade. By the late 1990s, these investments gradually paid off, leading to an improvement in GDP. Since then, the oil and gas industry has been a major contributor to economic growth in the country. The discoveries and dynamic legislation of large oil fields in areas such as the Gulf of Suez, Western Desert, Eastern Desert and Sinai, have strengthened the robust oil and gas industry and been a huge contributor to more rapid economic growth. In fact, by the 1990s, the country was a strategic oil producer based on fields in four areas — the Gulf of Suez, Western Desert, Eastern Desert and Sinai. By 2011, the sector was growing at unprecedented levels attracting nearly 70% of Egypt’s foreign direct investment. In recent years, the government under President Sisi, with the assistance of the IMF, has embarked on an economic reform agenda to restructure the economy. Through this, tax reforms have been introduced, while government expenditure has been cut down and several infrastructural projects such as the construction of a new capital city, a large nuclear energy project and a second canal parallel to Suez are intended to boost the economy.

Although the macroeconomic indicators improved, the country still suffers from the impact of fiscal and monetary instability. The economy is challenged in all spheres, including weakening domestic currency, high inflation rate, capital flight and rising public debt. Also, Egypt’s high growth rates have not translated into the needed jobs to reduce unemployment. The country’s long-standing challenges were further compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to slowed economic activity, the pandemic worsened the high unemployment rate (from 7.7% in 2019 to 9.6% in 2020) especially in the formal sector, creating a wider budget deficit. This also led to a drop in foreign reserves, tourism, Suez Canal revenues and merchandise exports.

Post COVID-19, the country is currently experiencing an economic downturn which perhaps is the most severe since 2011 with debt-to-GDP ratio significantly increasing to 92.7% in 2023. Similarly, annual urban inflation was rising to 33.8% by the end of 2023 mainly driving higher food prices, rising cost of production and expansionary monetary policies particularly in extending credit to the public sector.

While the country’s economic growth prospect is higher than its income peers, it will still lag behind its Vision 2030 targets if nothing is done to accelerate its development potential and harness its economic opportunities. Even by 2030 which is the end of the implementation of the vision, Egypt will not meet its growth target of 12% on the Current Path. Indeed, by 2043, the average growth rate will be about 4.7% far below the desired target in Vision 2030.

Despite the negative economic repercussions, Egypt’s economic outlook remains positive with expected strong growth based on the IMF projections. Nonetheless, the country needs to deal with the many structural difficulties and economic vulnerabilities, particularly on issues related to stabilising the economy, underperforming non-oil sector, job creation mechanisms, the business development environment and rising government debt. On the Current Path, Egypt’s GDP is estimated to more than double to US$826 billion by 2043. The increase in GDP reflects the higher rate of economic growth expected to occur within the next 20 years.

Chart 6 presents the size of the informal economy as per cent of GDP and per cent of total labour (non-agriculture), from 2019 to 2043. The data in our modelling are largely estimates and therefore may differ from other sources.

Compared to most oil-rich Gulf countries, Egypt has a large informal sector. It accounts for about 68-70% of all new jobs and grows by 1% every year. The country is inundated with several small businesses that are unable to offer formal employment to the teeming labour force. Estimates show that 53% of establishments in Egypt are considered informal businesses.

The size of the informal sector in Egypt was equivalent to 20.5% of GDP, representing US$67.2 billion, in 2023, which was below the average of 29.2% for lower-middle-income African countries. Among Africa’s 24 lower-middle-income countries, only Algeria has a smaller informal sector. This suggests that compared to its income peer group, Egypt has performed relatively better in formalising its economy. However, other estimates show that informality in Egypt may be higher than this. Indeed, it is estimated that the informal sector contribution to GDP ranges between 29.3% to 50% of GDP depending on the data sources used. Such a large informality denies the government the needed tax revenue for development. The size of the informal sector will slightly decline to 18.2% of GDP by 2043 equivalent to US$150.4 billion and below the average of 26.3% for its income peers in Africa.

The informal sector contributes significantly to employment creation in Egypt. In 2023, 50.4% of the total labour force in Egypt were employed in the informal sector making it the tenth-largest among Africa’s lower-middle-income countries. Although this was below the 55.5% average for lower-middle-income countries in Africa, it's very high particularly compared with the contribution of the sector to GDP. This may be due to the high levels of informal employment within the formal sector. Many larger firms do not offer formal employment, as only about half of employees in such firms have contracts and social insurance. Another reason could be that our modelling underestimates the informal sector’s contribution especially as other sources estimate a much larger value, as explained above.

An important feature of informal employment in Egypt is that it is more prevalent among vulnerable age groups: youth (between 15 and 24 years) and aged (65 years and above). Almost 93% of all working-aged and 90% of young people working are employed in the informal sector.

A World Bank analysis shows that Egyptian workers in the informal sector crave stability and job security, as most jobs lack written contracts or social insurance. Also, most workers in the sector indicate that they are willing to work for even 20% lower wages in the formal private sector due to the job security that comes with it. In fact, Egypt ranks among the 10 worst countries (out of 149 countries) for working people in the International Trade Union Confederation’s (ITUC) Global Rights Index report of 2024. Together with its large youth bulge, the survivalist employment in the informal economy could be a key driver for socio-economic unrest.

On the Current Path, informal labour will decline to 45.5% by 2043 which will still be below the average for its income peers in Africa. By 2043, the size of the informal sector in Egypt will be about 6.6 percentage points lower than the average for lower-middle-income African countries.

Chart 7 presents GDP per capita in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

Despite its limitations, GDP per capita is generally used to measure the standard of living and is the most widely used and accepted indicator to compare welfare among countries. Egypt has the highest GDP per capita among the 24 lower–middle-income countries in Africa. Using the purchasing power parity (PPP) measure for this analysis, it’s GDP per capita of US$12 070 in 2023 was almost twice the group average of US$6 127. This figure represents a tremendous improvement (almost 100%) from the US$6 297 it recorded in 1990. This GDP per capita is due to its relatively high economic growth and slower population growth which ensures that gains from growth are higher than compared to the average of its income peers. On the Current Path, Egypt will still have the largest GDP per capita among its peers at US$17 190 by 2043. At this rate, the country’s GDP per capita will be more than twice the average of US$7 942 for its income-group peers in Africa.

Chart 8 presents the rate and numbers of extremely poor people in the Current Path from 2019 to 2043.

In 2015, the World Bank adopted US$1.90 per person per day (in 2011 prices using GNI), also used to measure progress towards achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 1 of eradicating extreme poverty. In 2022, the World Bank updated the poverty lines to 2017 constant dollar values as follows:

- The previous US$1.90 extreme poverty line is now set at US$2.15, also for use with low-income countries.

- US$3.20 for lower-middle-income countries, now US$3.65 in 2017 values.

- US$5.50 for upper-middle-income countries, now US$6.85 in 2017 values.

- US$22.70 for high-income countries. The Bank has not yet announced the new poverty line in 2017 US$ prices for high-income countries.

Monetary poverty only tells part of the story, however. In addition, the global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) measures acute multidimensional poverty by measuring each person’s overlapping deprivations across 10 indicators in three equally weighted dimensions: health, education and standard of living. The MPI complements the international $2.15 a day poverty rate by identifying who is multidimensionally poor and also shows the composition of multidimensional poverty. The headcount or incidence of multidimensional poverty is often several percentage points higher than that of monetary poverty. This implies that individuals living above the monetary poverty line may still suffer deprivations in health, education and/or standard of living.

Egypt has seen significant progress in many human development indicators but still experiences a number of challenges. As a lower-middle-income country, Egypt uses the US$3.65 benchmark for extreme poverty. According to the World Bank macro poverty data, 17.8% of Egyptians lived below the poverty line of US$3.65% in 2010. In 2023, 18.8 million Egyptians, representing 16.7% of the population, lived below the poverty line of US$3.65, far below the average of 46.4% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. It means that over the past decades, the country’s effort at poverty eradication has yielded some results as the poverty rate declined below the average for its income peers in Africa. This is partly due to the government's implementation of its Haya Karima (Decent Life) initiative that has accelerated poverty reduction, particularly in rural areas.

Aside from income poverty, Egypt also experiences multidimensional poverty. According to the 2023 Human Development Report, Egypt was ranked 106th out of 204 states. Although this was an improvement over previous scores, it still has gaps in nutrition, school attendance, years of schooling, housing and even sanitation with 5.2% of the Egyptian population considered to be multidimensionally poor. Roughly 6.1% of the population is categorised as vulnerable and 0.6% are in severe poverty, with these figures disproportionately affecting those in rural areas. Regional inequalities and disparities also persist. Most of the poor and vulnerable population lives in the governorate of rural Upper Egypt especially in places such as Assyout, Sohag, Luxor and Minya. Based on the 2018 Household Income and Expenditure Survey, about 52% of people within this area cannot afford basic needs including food. The government reported that between the 2017/18 and 2019/20 financial year, household income in urban areas grew by 16% compared to 13% in rural areas. However, poverty rates in rural areas dropped faster than in urban areas, pointing to income polarisation and the difference in how people in rural and urban areas experience poverty.

On the Current Path, Egypt’s progress in reducing poverty rates will be more rapid compared to the average of its income-group peers in Africa such that by 2043, the poverty rate of 8.7% (equivalent to 12.6 million Egyptians) will be about 24 percentage points lower than the average for lower-middle-income countries in Africa.

Chart 9 depicts the National Development Plan.

The Sustainable Development Strategy: Egypt Vision 2030 is the broad framework for attaining Egyptians' dreams and aspirations of an advanced and prosperous nation inspired by the ancient Egyptian civilization’s achievements. Its overall vision is that “By 2030, Egypt will be a country with a competitive, balanced, and diversified economy, depending on knowledge and creativity, and based on justice, social integration, and participation, with a balanced and varied ecosystem, a country that uses the genius of the place and the citizens in order to achieve sustainable development and improve the quality of the life for all. Moreover, the government looks forward to lifting Egypt, through this strategy, to a position among the top 30 countries in the world, in terms of economic development indicators, fighting corruption, human development, market competitiveness, and the quality of life.”

The plan, developed on the principles of the sustainable development concept, intends to improve the quality of life of the present generation without compromising the right to a better life for future generations. Also, to ensure complementarity between the targets of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and Egypt’s Vision 2030, efforts were made to incorporate the SDGs targets into the Egyptian national planning system. This was the first nationally formulated strategy prepared in accordance with long-term strategic participatory planning. It incorporated broad stakeholder participation with strategic inputs from civil society, the private sector, ministries, and government agencies, women, youth and the disabled. In addition, the plan was formulated with the support and participation of international development partners.

The plan is broken into three dimensions, namely economic, social and environmental and further broken down into ten pillars. The economic dimension consists of the pillars of economic development; energy; knowledge, innovation and scientific research; and the transparency and efficiency of government institutions. The social dimension also comprises pillars of social justice; education and training; health; and culture. The final dimension of the environment involves the pillars of environment and urban development. There are also two additional pillars of domestic policy as well as foreign policy and national security, which serve as the comprehensive framework for the strategy and determination of the other pillars.

Each pillar consists of strategic targets, sub-targets, performance indicators, planned quantitative targets, expected challenges, and the appropriate programme and project sequence for execution based on priority. The strategic visions build on previous visions such as Egypt’s Strategy 2017, The Strategic Framework of Income Multiplying 2022 and the Urban Plan, 2052. In all, there are over 330 performance indicators and 50 associated strategic targets that are to be achieved through implementing about 200 programmes and projects.

The eight sectoral scenarios as well as their relationship to the Current Path and the Combined scenario are explained in the About Page. Chart 10 summarises the approach.

Chart 11 presents the mortality distribution in the Current Path from 2019 to 2043.

The Demographics and Health scenario envisions ambitious improvements in child and maternal mortality rates, enhanced access to modern contraception, and decreased mortality from communicable diseases (e.g., AIDS, diarrhoea, malaria, respiratory infections) and non-communicable diseases (e.g., diabetes), alongside advancements in safe water access and sanitation. This scenario assumes a swift demographic transition supported by heightened investments in health and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WaSH) infrastructure.

Visit the themes on Demographics and Health/WaSH for more detail on the scenario structure and interventions.

Although it is a developing country, Egypt’s current health profile largely mirrors that of developed countries. The success of Egypt’s long-running reforms has manifested in reduced incidents of communicable diseases, and longer life expectancy, among others. Some of the key accomplishments include a drastic decrease in rates of maternal and child deaths and chronic malnutrition. They also include the elimination of diseases like polio in 2006 and the establishment of a community health worker programme as a primary foundation towards equity in the provision of healthcare services. About 95% of its population lives within a 5 km radius of a health facility. It has also implemented the Social Health Insurance law towards achieving universal health coverage for its population.

However, alongside the successes, a range of other health issues plague Egypt’s ambition of an efficient health system beyond primary care services. The Egyptian Medical Syndicate estimates that between 2016 and 2019, out of the 220 000 registered doctors, 110 000 left the country. This means that Egypt has only 10 doctors per 10 000 people, trailing the global average of 32 per 10 000 people. Also, services in the public health sector are generally of low quality due to underfunding, lack of medical equipment and qualified personnel, poor sanitation and safety measures especially in rural areas. In 2016, it was estimated that Egypt had only 1.5 beds per 1 000 people relative to the global average of 2.7 per 1 000 people. The COVID-19 pandemic has further strained and exposed a struggling health system. All these challenges are impeding efficient healthcare delivery in the country.

Our modelling uses the International Classification of Disease (ICD) to differentiate between three broad categories of diseases: communicable, non-communicable and injuries, as well as 15 subcategories of mortality and morbidity. Unlike many African countries where communicable diseases are prevalent and leading cause of deaths, the reverse is the case in Egypt. Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) have been on the rise in Egypt, particularly since 1990, and will remain the leading causes of deaths in the country well beyond 2050.

In 1990, non-communicable diseases caused about 264 000 deaths — representing about 58% of total deaths in that year. This was followed by communicable diseases that caused 151 000 deaths (33.3% of total deaths) and injuries that caused 40 000 deaths (8.8% of total deaths). It signals that the country has undergone an epidemiological transition where deaths from non-communicable diseases outweigh deaths from communicable diseases. By 2023, 85.5% of all deaths in Egypt were from non-communicable diseases, translating into 571 000 deaths. This confirms World Health Organization estimates that more than 85% of total deaths in Egypt are caused by NCDs. Rising NCDs in the country is exacerbated by the prevalence of other behavioural and biological risk factors like smoking, unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, obesity and hypertension.

Also, deaths from injuries slightly increased to 50 000 equivalent to 7.5% of all death. However, deaths from communicable diseases had steadily declined to 47 000, (equivalent to 7% of all deaths) making it the lowest caused of deaths in the country. Among non-communicable diseases, death from cardiovascular diseases is the highest causing 47.3% of deaths in the country. This is followed by deaths from digestive and malignant neoplasm diseases which account for 12.5% and 10% of total deaths in the country respectively. There is also a high prevalence of strokes, cancer, diabetes, respiratory infections and other lifestyle diseases that are inherently more expensive to treat. Smoking for example is widespread, with roughly 20% of the population using tobacco products daily. In 2015, it was reported that the prevalence of diabetes was 16.7% in people between the ages of 20 and 79, representing 7.8 million cases at the time. Obesity among adults was over 33% higher than in some developed countries and one of the highest in the MENA region. The rate of hypertension among adults stood at nearly 25%, one of the highest in the world. This trend of declining communicable diseases but rising non-communicable diseases and injuries is set to continue on the Current Path.

By 2043, non-communicable diseases will still be the highest cause of death in Egypt causing 895 000 deaths in the country (about 88.8% of all deaths). By then, deaths from communicable diseases will rapidly decline to 36 000, constituting 3.6% of all deaths, while deaths from injuries will constitute the remaining 7.7%. This rising deaths from non-communicable diseases as the main cause of mortality in the country will inevitably increase health sector costs as they are more expensive to treat and put pressure on health budget which is already limited.

Investment in water and sanitation is critical for sustained human development in Egypt. In 2023, all Egyptians had access to improved water with almost 98.8% of the population having access to piped water supply in the country. Access to improved, safe, treated water, such as piped water, is an important means of preventing the spread of communicable diseases. It is therefore not surprising that the country records very minimal communicable diseases. This trend will continue although by 2043 the proportion of Egyptians with access to piped water will slightly decline to 94% while the remaining population will have access to other improved water sources.

Despite this universal access, the country will experience a critical water shortage by 2025. The Nile Basin is Egypt’s largest water source, with an allocated annual flow of 55.5 billion cubic metres. Ground and surface water sources account for about 0.5 billion cubic metres. The Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System in the Western Desert is also another important water source, but this is fossil groundwater which comes with the risk of contamination. However, Egypt requires about 90 billion cubic metres of water annually to meet its national needs and currently the water supply records a deficit of about 34 billion cubic metres. In 2018, the annual per capita share of water declined to 570 m3 which is below the set international standard of 1 000 m3. Also, the recent completion of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), could put a significant strain on Egypt's already scarce water resources, accentuating the possibility of conflict between the two nations. In addition, Egypt faces issues of water quality and its impact on the environment and human health. It also experiences water pollution from a range of sources including chemicals like pesticides and herbicides. Water pollution has led to diseases like bilharzia, especially in rural areas.

Meeting the population’s water demand, bridging the rural–urban divide and improving water quality will require major investment. The government has signed numerous agreements seeking more funding to build desalination plants and improve long-term sustainability of water access in Egypt. However, these must be accompanied by a drive for better water management and more efficient use of this scarce resource, especially in the agriculture sector. Without closing the water supply and demand gap, Egypt is facing an inevitable crisis.

Regarding sanitation, over 98% of all Egyptians had access to improved sanitation in 2023. Only 1.5% of Egyptians lived in conditions with access to shared sanitation. On the Current Path, this trend will remain by 2043. This signals that Egypt has already attained SDGs goals 6.1 and 6.2 on universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water and sanitation for all.

The National Rural Sanitation Program established by the Ministry of Housing, Utilities and Urban Communities has set a target to expand and improve nationwide access to sanitation services from. This would be through an integrated system of sewerage networks, sludge treatment and wastewater treatment plants. One of the initiatives under this programme, the Integrated Rural Sanitation in Upper Egypt-Luxor project, approved in 2019 and signed in 2021 received a US$129.8 million (€109 million) loan from the African Development Bank. This was to improve sanitation infrastructure and services to rural communities in Luxor Governorate in Egypt’s Upper Nile region.

Chart 12 presents the infant mortality rate in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2019 to 2043.

The infant mortality rate is the probability of a child born in a specific year dying before reaching the age of one. It measures the child-born survival rate and reflects the social, economic and environmental conditions in which children live, including their health care. It is measured as the number of infant deaths per 1 000 live births and is an important marker of the overall quality of the health system in a country.

The infant mortality rate is an important marker of the overall quality of a country’s health system. In 2023, the infant mortality rate in Egypt was 11.6 deaths per 1 000 live births—a significant drop by 448% from the rate in 1990. This was also just about a quarter of the average of 42.5 deaths for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. It means that Egypt has already met SDG goal 3.2.1 of reducing infant mortality to 12 deaths per 1 000 live births. On the Current Path, the infant mortality rate will decline further, reaching 7.7 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2043, which will still be far lower than the average of 29.4 per 1 000 live births for its lower-middle-income countries in Africa. Due to the high reduction rate that is forecast to occur in the Current Path, the Demographics and Health scenario will modestly reduce Egypt’s infant mortality rate to 6.3 deaths per 1 000 births by 2043. This is 1.4 deaths fewer than in the Current Path and almost twenty three fewer deaths than the Current Path average of lower-middle-income countries in Africa.

Chart 13 presents the demographic dividend in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2019 to 2043.

Demographers typically differentiate between a first, second and even third demographic dividend. Given Egypt’s youthful population structure, and the strides made in the past two decades, the study focuses on the first dividend. There are different ways to conceptualise the first demographic dividend. For example, studies have shown that a promising demographic window occurs when less than 30% of the population falls within the ages 0–14 years (children) while those above the age of 65 years and above (elderly) make up less than 15%. Alternatively, a demographic dividend opens when a country attains an average median age of between 26 and 41 years. We generally use the ratio of working-age persons to dependants, i.e. the size of the labour force (between 15 and 64 years of age) relative to dependants (children and elderly people).

The demographic dividend is the economic growth generated by change in the population structure. It generally materialises when the ratio of the working-age population to dependants is at least 1.7-to-1, meaning that for every dependant, there are 1.7 workers. When there are fewer dependants to take care of, it frees up resources for investment in both physical and human capital formation. Studies have shown that about one-third of economic growth during the East Asia economic ‘miracle’ can be attributed to the large worker bulge and a relatively small number of dependants. However, the growth in the working-age population relative to dependants does not automatically translate into rapid economic growth unless the labour force acquires the needed skills and is absorbed by the labour market. Without sufficient education and employment generation to successfully harness their productive power, the growing labour force (especially those in urban areas) could increasingly become frustrated with the lack of job opportunities leading to social tension and even the emergence of civil instability.

In 2023, the ratio of the working-age population to dependants in Egypt was 1.65-to-1, which means that on average, for every dependant in Egypt, there were 1.65 people of working age (15–64 years of age). This is significantly above the 1.36-to-1 average for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. The low dependency rate in Egypt can be attributed to the relatively low fertility rate. On the Current Path, Egypt will achieve the minimum ratio of 1.7 working age persons for each dependant required for the materialisation of the demographic dividend, or demographic gift, by 2026. By 2043, the ratio of the working-age population to dependants will be 2.0-to-1, far above the average for its income peers of 1.56-to-1. The Demographics and Health scenario will push the ratio further such that by 2043, the ratio of the working-age population to dependants will be 2.4-to-1 in the scenario with positive effects on productivity and economic growth.

Chart 14 presents crop production and demand in the Current Path from 1990 to 2043.

The Agriculture scenario envisions an agricultural revolution that ensures food security through ambitious yet feasible increases in yields per hectare, thanks to improved management, seed, fertiliser technology, and expanded irrigation and equipped land. Efforts to reduce food loss and waste are emphasised, with increased calorie consumption as an indicator of self-sufficiency and prioritising it over food exports. Additionally, enhanced forest protection signifies a commitment to sustainable land use practices.

Visit the theme on Agriculture for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

The agricultural sector provides employment to about 28% of the population, 45% of women and 55% of people in Upper Egypt. The Nile’s predictability and Egypt’s fertile soil have allowed the country to build significant agricultural wealth over the years. Egypt’s agricultural land is estimated to be about 360 km2, representing only about 3.9% of the country’s total land area. The area of cultivated land per person is only about 0.05 hectare, one of the lowest globally. Most of that is located in a narrow strip along the Nile Delta and ‘new lands’ reclaimed from the desert after the construction of the Aswan Dam.

The major challenges facing the future of agriculture in Egypt include scanty rainfall, loss of agricultural land to urbanisation and the impact of Egypt’s dispute with Ethiopia on the Nile water upon which it relies for irrigation. There are also climatic factors, such as flood arising from the Nile River Delta, which constrain agricultural production. High production and consumption losses is further straining the sector. A 2015 study reported that out of the respondents surveyed, only about 14% indicated that they did not throw away food and that food waste increased during the fasting month of Ramadan.

In 1990, Egypt’s average crop yield of 17.4 metric tons per hectare was fourth highest in Africa and the highest among its income-group peers in Africa. By 2023, the average crop yield per hectare of 27.4 metric tons in Egypt was third highest in Africa after Mauritius and Eswatini and the highest among the lower-middle-income countries in Africa. This means that compared to its income-group peers, Egypt has been able to adopt improved technology and mechanised agriculture that significantly increased its yield per hectare. The country has leveraged on the Nile river to develop an irrigation system for large-scale mechanised agriculture. On the Current Path, yield per hectare will rise to 31.3 metric tons per hectare by 2043, which will be more than six times the average of lower-middle-income African countries. Sustaining Egypt’s agricultural yields will prove challenging in the face of increased population growth, controversy about the Nile water and limited and declining agricultural land.

Total agriculture production in 1990 stood at about 45 million metric tons. Of this, 41.9 million metric tons, representing 92.1%, were crops, with the remainder constituting meat production. By 2023, total agricultural production in Egypt had grown to 111.2 million metric tons. Of this, crop production constituted 89.7%, equivalent to 99.7 million metric tons, meat production 8.3%, and fish production constituted the remainder of the total production.

Egypt faces huge crop loss and waste estimated at 19.3% of total production. This is largely due to post-harvest losses for crops, estimated at 7.5% of production, and transmission losses for crops, at 8.5.%. Such losses can be a result of pest and disease infections, spoilage and the lack of adequate and effective storage facilities. Fish and meat also witnessed loss and waste accounting for 29.7% and 20% of total production respectively.

There are efforts to improve agriculture production in the country. The Government is on a drive to reclaim more land for agriculture with a target of an additional 150 000 acres (60 000 hectares) per year. The government is also taking initiatives to boost domestic production and promote sustainable and green farming. Despite these efforts, much more needs to be done to make the agricultural system more efficient and better geared towards policies that incentivise farmers to focus on food products for which Egypt has a comparative advantage.

In terms of demand, the total demand for agricultural products in Egypt has always been more than the total production. Total demand stood at about 55.3 million metric tons in 1990, of which 50.7 million metric tons, equivalent to 92% of total demand, were for crops. The remaining demand was for meat (4.1 million tons) and for fish (510 000 tons). Since then, domestic demand has rapidly outgrown production, and by 2023, agricultural demand exceeded domestic production by 23.5 million metric tons, despite the increase in production. Of the total demand of 134.7 million tons, 90.1% is for crops (122 million tons). The remaining demand is for meat (9.8 million tons) and for fish (2.9 million tons). Despite the increase in domestic production, reaching 136.5 million metric tons in 2043, it will not be enough to meet domestic demand that will rapidly grow to 189.2 million metric tons. As a result, excess demand for agricultural products will reach 52.7 million by 2043. This indicates that Egypt faces the risk of food shortages in the future if drastic measures are not taken to revamp the agriculture sector to increase domestic production.

With total agricultural demand outgrowing domestic production, Egypt will have to rely on imports to meet its domestic demand. In 2023, Egypt’s net import of crops stood at 19% of total crop demand, which was more than the average of 13.4% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. Also, net import of fish stood at 39% of total fish demand, while net import of meat was estimated at just 1% of total meat demand. Commodities such as wheat, lentils, red meat, sugar and oils are mostly imported as domestic demand outstrips local production capacity. For instance, in 2019, Egypt imported US$4.67 billion in wheat, becoming the 1st-largest importer of wheat globally. However, Egypt is food-sufficient when it comes to commodities like rice, fruits, vegetables, poultry and dairy products.

In light of its huge population, shrinking agricultural land, water scarcity and other effects of climate change, Egypt remains food insecure and vulnerable to international price shocks and disruptions in supply chains. In the Current Path, net crop imports will grow in Egypt to 30.1% of total crop demand by 2043. This suggests a growing level of national food insecurity; however, it can also be as a result of changes in dietary preferences. Greater import dependence makes Egypt more vulnerable to international price shocks and accompanying risks of disruptions in the global supply chains as seen during COVID-19. Thus, while Egypt has increased agricultural production, the sector needs major reform to focus and incentivise production of goods like vegetables and fruits in which Egypt has a comparative advantage.

Chart 15 presents the import dependence in the Current Path and the Agriculture scenario, from 2019 to 2043.

In the Agriculture scenario, yield per hectare will increase to 33 metric tons by 2043 — a 5.4% improvement compared to the Current Path and over five times the average of lower-middle-income countries in Africa. The improvement in yields will lead to an improvement in total agricultural production. By 2043, in the Agriculture scenario, total production will increase to 143.8 million tons, almost 7.2 million metric tons, or 5.3%, more than the Current Path by 2043. Annual crop production in Egypt will rise by 6.4% over the Current Path to 115.1 million tons in the Agriculture scenario by 2043. The increases in crop production in the Agriculture scenario reduces the import dependency of crops in the country compared to the Current Path. By 2043, net import of crops will reach 24.4% in the Agriculture scenario — 6 percentage points less than Current Path and the average of its income-group peers in Africa.

Chart 16 depicts the progress through the educational system in the Current Path for 2019 to 2043.

The Education scenario represents reasonable but ambitious improved intake, transition and graduation rates from primary to tertiary levels and better quality of education at primary and secondary levels. It also models substantive progress towards gender parity at all levels, additional vocational training at the secondary school level and increases in the share of science and engineering graduates.

Visit the theme on Education for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

The public education system in Egypt consists of four stages of learning. The basic and compulsory education stage for children between four and 14 years comprises kindergarten for two years followed by primary school for six years and preparatory school (ISCED Level 2) for three years. Then, the secondary school (ISCED Level 3) stage is for three years, for ages 14/15 to 17, followed by the tertiary level. After independence Egypt introduced many educational initiatives and reforms, and the education system has made significant strides with improved educational outcomes in recent decades. The literacy rate stood at approximately 74% in 2020, while the number of elementary-age out-of-school children has dropped after rapid increases following the 2011 revolution.

Despite many initiatives, including compulsory education, the sector still faces numerous challenges. Key among these is Egypt’s rapid population growth, whose ramifications have been borne in the education sector through sharp increases and demand for enrolment both at primary and secondary level. This means greater funding requirements, capacity shortages and overcrowded learning facilities, particularly in denser regions like Cairo, Alexandria and Giza. Although the teacher-student ratio has risen in the past few years, teacher salaries have fallen. In 2017, the average teacher salary was about £86 000 (US$4 800). This is just 1.3 times the average GDP per capita of Egypt and way below the World Bank recommended average teacher salary of 3 to 3.5 times the GDP per capita for a productive education system. Due to the inadequacy of the education system, many skilled teachers have turned to private tutoring, which pays better than the public education system. An estimated 42% of household income is spent on after-school tutoring, but some learners drop out of school because they cannot afford to sustainably access supplementary tutoring.

In 2023, Egypt spent US$12.5 billion on its education system — this amount is equivalent to 3.8% of the country’s GDP. At this rate, Egypt’s spending on education was below the average of 4.5% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. On the Current Path, Egypt’s total expenditure on education will reach US$31.1 billion, constituting 3.8% of GDP, by 2043. About 35.3 of spending on education in Egypt is on the tertiary level making it the largest educational expenditure in the country. This departs from the trend observed in most African countries where much of the spending is done at the primary or lower secondary level. The high spending at the tertiary levels is partly explained by the high cost of training students at the tertiary especially in the sciences and engineering compared to other levels. On average, it costs US$1 365 to educate a student at tertiary level. This is almost 3 times what was spent on upper secondary students, 4.6 times the cost of educating a child at the lower secondary level and 5.2 times more than what it costs to educate a primary level student. Nonetheless, spending at the primary level constitutes 33.2% while spending on lower and upper secondary levels constitute 16.1% and 15.9% respectively.

The education system can be viewed as a long funnel where children enter at the primary level and exit after completing tertiary-level education. Many children that enter the system at the wide mouth of the funnel, but few complete the entire journey — from primary to secondary school and then university — to eventually graduate with a tertiary or equivalent education at the other end. However, the education funnel in Egypt largely mirrors that of a developed country with less leakages and cracks along the way. In 2023, the gross enrolment rate for primary school students in Egypt was 104.2%, an increase from 91.0% in 1990 higher than the average of 101% of lower-middle-income countries in Africa. Comparing this to the net enrolment rate of almost 99.6% in the same period leads to two important conclusions. Firstly, almost all children in Egypt who are of school-going age are in school. Secondly, many classrooms in Egypt are likely to be filled by children of the appropriate age group compared to most other African countries where classrooms are crowded by older students. On the Current Path, Egypt's gross and net enrolment rates will be the same, reaching 100% by 2043.

The gross primary completion rate stood at almost 100% in 2023, indicating that almost all children who enrolled in primary school completed the last grade in Egypt which departed from the trend in most low- and lower-middle-income countries in Africa that usually have high dropout rates. On the Current Path, Egypts progress in ensuring more children complete primary school will be maintained throughout the forecast period such that by 2043, almost every primary school student will complete the last grade. This progress in Egypt mirrors that of a developed country and advanced educational system where access at the basic level is universal and an older population that is highly educated. Of those who complete primary level education, some will transition immediately to the lower secondary level, some will enrol in the lower secondary level after some years out of school and some will never enter the lower secondary level, and so on through the upper secondary and tertiary levels.

In Egypt, more students transition from primary level to lower-secondary level than they do from lower secondary level to upper-secondary level. In both cases, the rates are higher than Egypt's income-group peers in Africa: gross enrolment for lower- and upper-secondary levels in the country stood at 93.1% and 72.4%, respectively, in 2023. These rates are far above the averages of 71% and 45.9% for its income peers. The high enrolment rates at the primary and secondary levels is due to Egypt’s free and compulsory education for children between ages 6 to 15 years. However, this put pressure on teaching and learning materials particularly in densely populated areas such as Cairo, Alexandria and Giza. As a result, about 30% of school children particularly in the rural areas lack learning materials.

By 2043, gross enrolment for the lower-secondary level will rise to 95.6%, while that of the upper-secondary level will rise to 82.3%. In 2023, completion rates stood at 81.9% in the lower-secondary level while that of upper-secondary level was 69.2%. Although these rates are far above the average for its income peers in Africa (53.2% for lower-secondary and 35.8% for upper-secondary), it is an indication of a contraction in the educational funnel in Egypt. By 2043, 90.9% of students will complete their lower-secondary education compared to 77.7% in upper-secondary level.

At tertiary level, the situation is less rosy. In its effort to expand capacity in the tertiary sector, Egypt has successfully sought to establish itself as a major higher learning destination. It has attracted many foreign learners from the MENA region and sub-Saharan Africa mainly due to its low tuition and living expenses, scholarships, free admission of non-citizens and international partnerships. The country also hosts many reputable international universities like the American University in Cairo, the German University in Cairo, the British University in Egypt, and the Université Française d’Egypte. Furthermore, in 2018, Egypt enacted legislation to attract more international universities to establish their foreign branches in the country with more streamlined licensing procedures, affordable real estate, tax breaks and requirements to teach the same programmes as in their home countries. These policies are meant to enhance the global competitiveness of Egypt’s education system, increase capacity and intake, enhance performance of domestic universities by increasing competition, foster research collaboration and inbound student mobility, and ultimately improve the stock of human capital in the country.

Despite these efforts, enrolments in the tertiary level remain low. In 2023, only 34.4% of people within the age group were enrolled in tertiary institutions in Egypt, and this will only improve to about 41.4% by 2043 on the Current Path. Although this is low, it is almost twice the average rate for lower-middle-income countries in Africa of 18%. About 31% of the relevant age group in Egypt graduated from a tertiary institution with at least a first degree in 2023 and will slightly rise to 35.4% by 2043. This is nearly three times the average rate in lower-middle-income countries although the gap between Egypt and its income peers will close over the forecast period.

Egypt has done well to eliminate the gender gap in access to education Unlike its income peers, there is no gender inequality in access at the primary level as the ratio of females to males enrolment and completion are 100% in Egypt and forecast to continue on the Current Path even by 2043. At secondary level, there were 98 females enrolled in lower-secondary schools for every 100 males in Egypt, as opposed to the average of 95 females for every 100 males in lower-middle-income Africa. At the upper-secondary level, there were 96 females for every 100 males in Egypt, almost at par with the average of lower-middle-income African countries in 2023. However, the ratio is lower when it comes to completion. In 2023, there were 89 and 98 females who completed in lower- and upper-secondary schools respectively for every 100 males in Egypt. At tertiary level, the gap is closed as it reaches parity with the ratio of females to male students almost similar to the average of its income group in Africa.

Vocational training has always been a large part of Egypt’s education system. Under Mubarak, one of the best-known schemes — originally called the Mubarak-Kohl Initiative, now known as the dual system — was launched in 1994 by the Ministry of Education and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit to promote technical training. Since 2015, other technical and vocational education and training (TVET) schemes such as the ‘Integrated TVET scheme’ and ‘Life-long learning’ (Oumal System) have been rolled out by the government, with a strong emphasis on apprenticeship. Although these efforts have scaled up TVET programmes, increased training opportunities are still needed in Egypt. The government envisions a 50% increase in the dual education system in all schools by 2025. This would be a huge increase in the number of trainees undergoing TVET training.

Enrolments in vocational training and science and engineering education, which are considered crucial to the future of work, are quite encouraging. In 2023, about 46.8% of upper-secondary school students were enrolled in vocational training programmes in Egypt. This is more than three times the average for lower-middle-income countries in Africa and the second highest in the group, only below the rates in Angola. On the Current Path, this trend will continue even by 2043. However, the engineering and science education at the tertiary level is relatively low in Egypt. In 2023, 11% of tertiary graduates in Egypt enrolled in science and engineering programmes. This was below the average of 16.6% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. However, on the Current Path, Egypt will close this gap so that by 2043, its rate of 19.2% will almost be at par with the 19.5% average for its income peers in Africa.

Beyond the limited access to education in the country, there are also problems with the quality of education. Educational outcomes are generally good, but bottlenecks have emerged at secondary and higher education levels. The country has a 0.49 score (the index ranges between 0 and 1) in the Human Capital Index of 2020 — a score slightly lower than the Middle East and North Africa’s average at 0.51 and slightly higher than that of sub-Saharan Africa (0.40).

In 2023, the average test score for primary and secondary students in Egypt stood at 38 and 43.5 out of 100, respectively. Both the primary and secondary test score for Egypt was above the average of 33.3 and 41.8 for its income-group peers in Africa respectively. Although Egypt performs relatively well at primary and upper-secondary levels, tertiary outcomes are quite poor relative to the comparison countries and groups. As a result, the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report for 2017/18 ranked Egypt’s quality of primary education at position 133 out of 137 countries — only two positions ahead of war-ravaged Yemen. The number and availability of qualified teachers and desire for teacher training and deployment into public schools is dropping and will continue to do so if the issue of teacher remuneration is not addressed.

Chart 17 presents the mean years of education in the Current Path and in the Education scenario, from 2019 to 2043, for the 15 to 24 age group.

The average years of education in the adult population (aged 15 years and older) is a good first indicator of the stock of knowledge in society.

In 2023, the mean years of education attained by adults between 15 and 24 years in Egypt stood at 8.8 years — below the average of 7.8 years for lower-middle-income countries on the continent. In the Current Path, the average Egyptian between the ages of 15 and 24 years will have received 8.5 years of education by 2043. On average, females received 0.4 years more schooling than males and forecast to remain till 2043. In the Education scenario, the mean years of adult education in Egypt will increase to 9.5 by 2043, 0.5 years more than the Current Path and higher than the average for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. The interventions in the Education scenario also close the gender gap in educational attainment in Egypt.