Securing momentum for Africa’s democracy

Concrete and coordinated actions must follow the election euphoria of 2024 to turn democratic gains into lasting progress.

Dubbed the Year of Elections, 2024 opened and closed with a great deal of optimism for Africa’s democratic project. Voters in several countries on the continent chose change and achieved it peacefully, for example, Senegalese voters massively backed the opposition Patriots du Sénégal party after a constitutional crisis triggered by then-President Macky Sall’s attempt to postpone the election. In Botswana, the opposition Umbrella for Democratic Change made history by defeating the Botswana Democratic Party, which had held power since the country’s independence in 1966. Opposition parties also won elections in Mauritius and Ghana, while the ruling African National Congress in South Africa was forced into a coalition government as it failed to retain its 30-year parliamentary majority.

The winds of change in 2024, driven by citizens’ aspirations for democratic and accountable governance, provide room for optimism about the future of democracy on the continent. Governments and democracy stakeholders, especially the African Union (AU) Commission, the regional economic communities (RECs), civil society groups and the international community, must act to sustain and build on this momentum. Improving the quality and efficacy of elections and the integrity of electoral institutions and processes should top the list of concrete actions they can take.

The winds of change in 2024 provide room for optimism about the future of democracy on the continent

Citizen views on elections: what we have learned so far

1. Robust and resilient demand

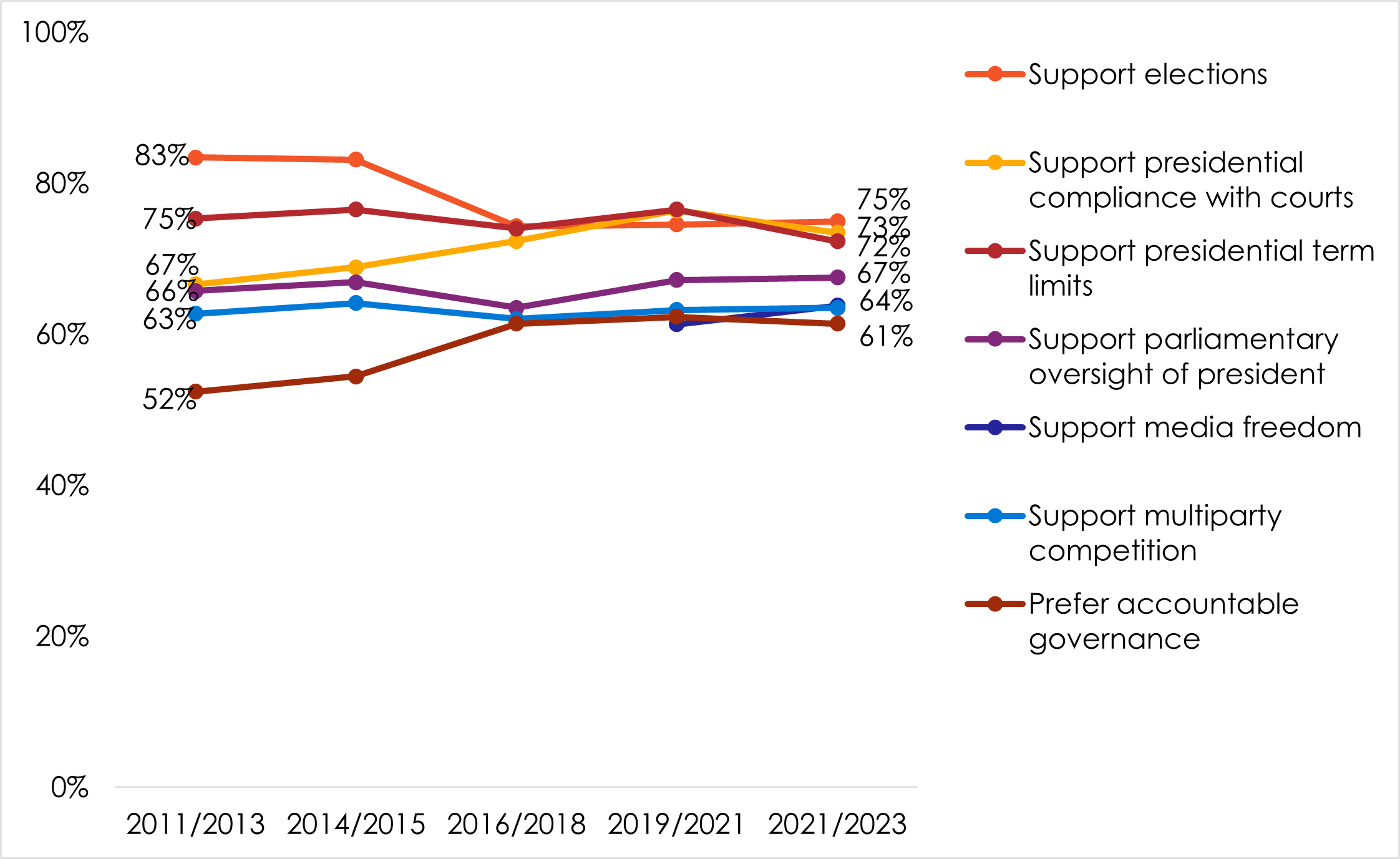

Over the past decade, Africans have consistently voiced support for the norms and institutions of democratic governance, including strong and enduring support for elections as well as for multiparty competition (see Figure 2 for over-time analysis). Results from Afrobarometer’s most recent surveys, conducted between late 2021 and mid-2023 in 39 countries with nationally representative samples of the adult population in each country, highlighted these trends in comparison to those from the 2011 surveys. For the 2021/2023 surveys, respondents were asked to confirm which of the two following statements was closest to their view. Statement 1 was: ‘We should choose our leaders in this country through regular, open, and honest elections.’ Statement 2 was: ‘Since elections sometimes produce bad results, we should adopt other methods for choosing this country’s leaders.’

The results show that an average of 75% of Africans endorse elections as the best method for choosing leaders (Figure 1). This includes overwhelming majorities in Liberia (92%), Sierra Leone (89%), Benin (86%) and Tanzania (86%). Lesotho is the only country where fewer than half (44%) endorse elections. Figure 1 depicts the percentage of respondents who “agree” or “strongly agree” with Statement 1.

Figure 1: Support for elections | 39 African countries | 2021/2023.

Perhaps reflecting some dissatisfaction with the experience of low-quality, disputed or violent elections, overall support for elections has weakened somewhat since 2011/2013, declining from 83% to 75% in 2023 across 30 countries surveyed consistently. Even so, the right to choose their leaders at the ballot box has remained one of the most popular features of democracy among citizens (Figure 2).

More than six in ten Africans also consistently say that ‘many political parties are needed to make sure that [citizens] have real choices in who governs them.’

Similarly, the data show steady majority support for the rule of law, presidential term limits, parliamentary oversight of the executive, and media freedom. These sentiments, coupled with a growing emphasis on government accountability are reasons for optimism about Africa’s democratic project.

Figure 2: Trends in support for democratic norms | 30 African countries* | 2011-2023. *Results for three questions do not include countries in which these questions were not asked in all survey rounds: on elections (Morocco), presidential compliance with courts (Sudan, Guinea, and Eswatini), and parliamentary oversight of president (Sudan, Guinea, and Burkina Faso).

2. Weak and declining supply of national electoral bodies

While majorities of Africans remain committed to democracy and its institutions, they are increasingly disappointed with the delivery of democratic goods by their elected leaders. Respondents were asked how much they trust (or whether they have not heard enough about them to say) their [national electoral commission].

The results show that fewer than four in 10 Africans (39%) say they trust their electoral management body (EMB) “a lot” or even “somewhat” (Figure 3). However, there is a large cross-country variation in popular trust in EMBs, ranging from 79% in Tanzania to only 16% in Gabon.

Across 27 countries for which we have data over time, trust in EMBs has been trending downward, declining by 9 percentage points between 2014 and 2023.

Figure 3: Trust in election management bodies | 38 African countries* | 2021/2023. *Question was not asked in Guinea.

Popular ratings of the freeness and fairness of national elections have also declined over the past decade. In 2014/2015, almost two-thirds of Africans across 31 countries rated their country’s elections as largely free and fair. Yet, by 2021/2023, only 58% held this view. When asked whether they think elections are effective in ensuring that members of Parliament reflect voters’ views and in enabling voters to remove non-performing leaders, fewer than half of Africans responded in the affirmative. And only 45% rate their country as “a full democracy” or “a democracy with minor problems.”

Afrobarometer analysis has shown that poor-quality elections are a key factor that undermines popular support for and satisfaction with democracy. In line with this finding, the proportion of Africans who are satisfied with the way democracy works in their country declined by 12 percentage points across 30 countries where we have over-time data.

The countries that led this decline in popular satisfaction with democracy are Botswana and Mauritius (both with 40-percentage-point drops), South Africa (-35 points), Eswatini (-25 points), Lesotho (-24 points), Ghana (-23 points) and Senegal (-20 points). Five of these seven countries conducted elections in 2024, and ruling parties lost power in four of them – Botswana, Ghana, Mauritius and Senegal – while the ruling ANC in South Africa also failed to hold on to its parliamentary majority.

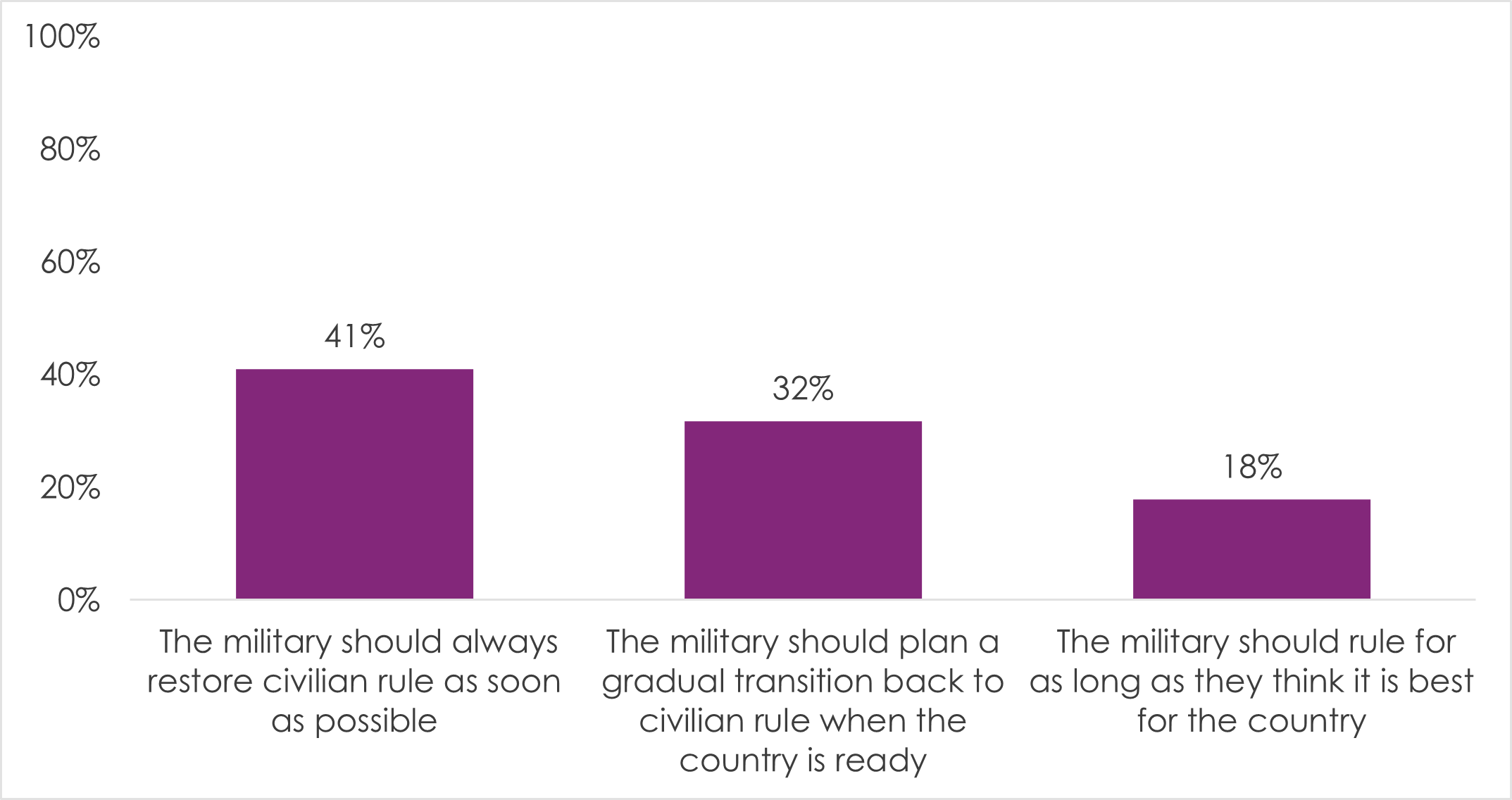

In hindsight, these outcomes were predictable from Afrobarometer data, suggesting that if elections work well to empower citizens, voters will communicate their dissatisfaction at the ballot box. Democracy stakeholders would do well to help ensure that Africa’s electoral institutions and processes work as intended. In particular, the transition elections in Gabon, tentatively scheduled for August 2025, present an excellent opportunity to leverage popular sentiment on the continent about the military in politics and to initiate conversations about transition arrangements in other military-ruled countries.

Respondents were asked: ‘If the military were ever to intervene in government, which of the following three statements is closest to your opinion?’ (Figure 4). While a slim majority of Africans are willing to accept military intervention if their elected leaders abuse power, two-thirds reject military rule. In cases where the military intervenes, citizens also disapprove of the military staying indefinitely: Across 17 countries surveyed in 2024, 41% of respondents say the military should always restore civilian rule as soon as possible, while 32% say it should plan a gradual transition to civilian rule.

Figure 4: Limits to military intervention in politics | 17 African countries | 2024.

Looking ahead: strengthening African electoral institutions and processes

Democracy stakeholders looking to fortify electoral institutions and processes in African countries face a long list of challenges, from uneven political playing fields and electoral infrastructure gaps to constrained media environments. One area where concrete steps could bring wide-ranging benefits is the coordinated use of technology.

The use of technology in election management, already widespread across the continent, carries significant risks and costs when individual countries make their own arrangements for election management technology and related resources. Effective coordination at the continental and possibly the sub-regional levels, facilitated by the AU Commission and the RECs with the active participation of civil society groups, election experts, and technology companies and experts, would help to minimise the risks and costs and maximise the benefits.

Here are two practical proposals on this front:

1. Strengthen the Association of African Election Authorities

This association was formed to foster dialogue, standards setting, and the exchange of lessons and best practices in election management. With robust support from civil society, private technology companies and experts, the AU and the RECs, a technically competent association would:

- Facilitate standardisation of legal and regulatory frameworks for integrating technology across electoral processes. Enforcement of technology-related policies governing electoral processes would be more effective as powerful private technology companies would have to contend with a continental network of stakeholders.

- Promote and protect the independence of the EMBs. Strong coordination at the continental level would bolster the independence of EMBs as officials would be assured of support and solidarity from their counterparts from other parts of the continent as well as from the AUC and RECs. The psychological safety and security offered by a large network would be a strong incentive for electoral officials to act independently and effectively resist external and/or political interference.

- Reduce costs and technical risks. Coordinated management and sharing of technology-related resources could help individual countries reduce costs and minimise or eliminate technical risks associated with software and other expert resources provided by foreign companies.

2. Designate an AU Special Rapporteur for electoral integrity

To ensure effective coordination among EMBs and other stakeholders and streamline the integration of technology in election management, it would be necessary for the AU to appoint a special rapporteur for electoral integrity on the continent. In addition to stakeholder coordination and streamlining the use of technology in elections and electoral processes, the special rapporteur could serve as the technical unit for the AU election observation missions.

With concrete steps like these, the 2024 momentum can be carried forward

With concrete steps like these, the 2024 momentum can be carried forward. The incoming chair of the AU Commission and the RECs would signal an important commitment to improving democratic and accountable governance on the continent and align well with the enduring aspirations of the majority of African citizens.

Image: U.S. Embassy, Idika Onyukwu/ Flickr