Powering Africa: the future of nuclear energy

Africa’s large base-load energy demand will require a substantial investment in nuclear.

In March 2024, we released our modelling results on Africa’s energy future, examining the long-term potential transition in a world that must rapidly move away from fossil fuels to limit global warming. This transition is crucial for expanding access to sustainable energy sources and ensuring equitable growth and development.

Two factors will determine Africa’s future energy landscape: demand and population growth. First, substantial increases in energy demand will accompany Africa’s development. Rapid development requires the availability of 8.62 barrels of oil equivalent per person. The average in Africa currently is 3.2 barrels, the lowest of any region globally. Second, Africa is experiencing rapid population growth. In 2022, Africa’s population reached 1.432 billion people, surpassing both that of India (still growing) and China (which has peaked). By 2063, Africa’s population (then at 3.1 billion people) will be almost double that of India, while China's will continue its steady decline.

Rapid increases in the energy needs of its growing population mean that Africa’s energy demand will, by around 2080, exceed that of China. That is if African economies continue to bumble at an average growth rate of around 4.5% annually, largely driven by its growing population. Faster growth as a result of productivity and other improvements will lead to even more significant increases in energy demand and associated carbon emissions.

Our modelling explored the extent to which Africa could transition away from fossil fuels, including coal, oil and gas. Oil currently accounts for 49% of Africa’s energy production, gas for 31% and coal for around 17%. Our Current Path forecast indicates that by 2050, oil will still account for 27% of Africa’s energy production, gas for 46% and coal for 5%. With considerable effort, reducing these numbers might be possible, particularly for oil and coal. Still, Africa is unlikely to be able to wean itself off gas, implying a slower transition away from fossil fuels than required to keep even a two-degree Celcius goal alive. The implication is that other regions would have to reduce emissions rapidly to provide space for those from Africa.

By 2080, Africa's energy demand will exceed China's if growth continues at 4.5% annually. Transitioning from fossil fuels, especially gas remains a challenge

Although much of its fossil fuels are exported, Africa is more fossil fuel dependent than any other region globally. This means that a small portion of its energy production comes from nuclear, hydro or renewables.

On the one hand, Africa’s limited fossil fuel infrastructure (such as refining capacity, pipelines, etc.) positions it well for a more rapid transition away from fossil fuels. However, given the growing domestic energy demand, Africans will likely use more of their fossil fuel energy production to meet domestic requirements, reducing exports.

Whereas other regions with higher energy production and slower-growing populations can transition away from fossil fuels, essentially replacing energy from coal, oil and gas with other sources, our modelling indicates that this will be more difficult in Africa. Energy production in Africa from ‘other renewables’, basically wind and solar, accounts for only 1.7% of total production. It will take a very long time to scale this up to take over some of the energy currently provided by fossil fuels. Wind and solar have a large potential to provide household electricity through off- and mini-grid applications in rural areas but will not resolve Africa’s base-load requirement. Without a breakthrough in energy storage, the intermittent nature of renewables presents a significant obstacle for countries looking to exploit their commodities and industrialise.

In surveying options, it appears that the only available technologies that could moderate Africa’s fossil-fuel-dependent energy pathway are nuclear and hydro. Both are expensive, take several years to build, and come with environmental challenges, not to mention that Africa currently has very few of either.

Hydro is also being threatened by climate change. For example, Zambia recently suffered from the impact of lower-than-average rainfall on its hydro which powers 86% of the grid. Hydro accounts for less than 3% of Africa’s energy production. Although several dams are being built, only the Grand Inga scheme in DR Congo would be large enough to make a significant difference in the contribution that hydro can make to energy production on the continent. The estimated capacity of Grand Inga is more than 40 GW but it faces numerous obstacles, including a US$80 billion price tag and its distance to larger consumer markets.

Nuclear and hydro are Africa’s alternatives to moderate its fossil-fuel dependence but both are costly, slow to build and face significant challenges

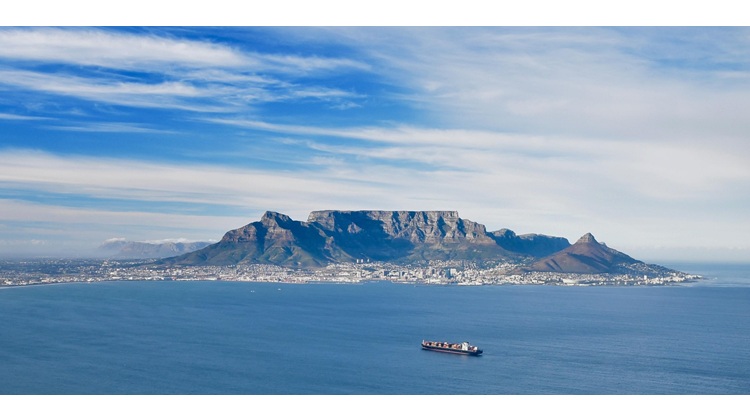

This leaves us with nuclear energy. The only operational nuclear plant in Africa is in South Africa. In 2022, Russia began constructing four large nuclear power plants with significant desalination capacity at El Dabaa in Egypt. These plants should come online as of 2026, eventually costing around US$30 billion. Even then, nuclear will account for less than 1% of Africa’s energy production.

According to the World Nuclear Association, nuclear power generates 10% of electricity, with about 60 reactors under construction and around double that number in the planning phase. Most of these are traditional, large-scale plants. However, micro, small, and modular nuclear reactors (SMRs) could play a much more important role in alleviating Africa’s energy challenge but probably remain a decade away from widespread commercial application. Russia and China have three SMRs in operation, and significant investments are being made in new designs.

The technology and safety concerns with SMRs all seem solvable. The main problem is that someone must place a large enough order to allow the construction of the first fleet of this new type of reactor. These would primarily be built in a production line process and have many advantages, but the first construction of such a new design is always very expensive. Essentially, an SMR could be deployed close to a fertiliser plant or industrial node to provide baseload energy capacity; it need not be part of a national grid. Or for desalination purposes, or next to a mine to ensure that it has dependable power. In South Africa, nuclear could replace the current fleet of coal fire stations by integrating SMRs into the grid in the province of Mpumalanga as coal plants are retired. For these reasons a number of African countries have expressed interest in nuclear including Kenya, Rwanda and others.

Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima mean that nuclear energy has a poor reputation but the emphasis on reducing carbon emissions has given the industry new momentum. New designs and features make it a viable future option for many African countries, where current technology does not appear to offer a base-load alternative. New partnerships and bold leadership will, however, be required to promote investment in peaceful uses that will ensure their safe, secure and responsible application as part of the solution and to encourage policy choices that balance urgent climate and development needs with public interest.

Image: Bjoern Schwarz/Flickr