World destabilising shocks and aid to Sub-Saharan Africa

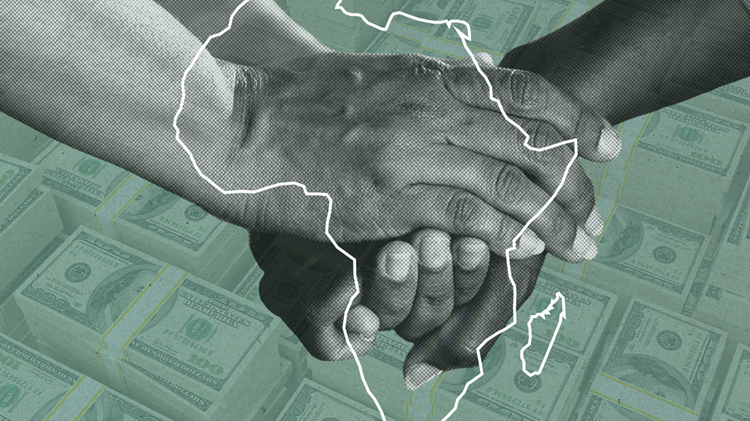

The geopolitical tensions between Russia and its allies, China and the West could affect aid flows to Africa.

Africa, particularly Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), has been dependent on aid for decades. With its 23 low-income countries, the continent is more vulnerable when there’s a decline in official development assistance (ODA) flows. Since most North African countries have now migrated to middle-income status, it’s predominantly the SSA countries that are more susceptible to potential shifts in aid flows.

The global economy continues to experience several destabilising shocks, and Africa won’t escape these episodes and their spill-over effects. The impact of COVID-19 highlighted the weaknesses of SSA countries in their ability to manage pandemics and to secure vaccines, and reaffirmed their dependencies on ODA.

Just when the world was slowly returning to normal in the wake of the pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sent another economic shock wave across the globe. Apart from its geopolitical polarising effect, it contributed to a shortage of gas, wheat, and fertilisers; rising energy and food prices; increased food insecurity; rising inflation; increase in government debt; and several other distortions.

From an economic point of view, the contraction of world economic growth at a time when it was recovering after the pandemic, as well as aspects such as food insecurity, will have a devastating effect on especially low-income and poorer nations in Africa. With a decline in world growth, aid flows could stagnate, decline, or even shift, with potentially devastating effects on government revenues and debt in aid-dependent countries.

The current global uncertainty and instability will impact the ODA and aid flow to SSA in the next few years

Although the mentioned world external shocks are unique in nature, it is always useful to look at what happened during the previous external shock period – the global financial crisis of 2008/9 – and its impact on aid flows to SSA. While world gross domestic product (GDP) growth slowed to 3.1% in 2008, it contracted to -0.1% in 2009, before recovering to 5.4% in 2010.

Growth in advanced economies, comprising most Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) donors, performed even worse. There was a stagnating average growth rate of 0.3% in 2008, a contraction in growth of -3.3% in 2009 and recovery to 3.1% in 2010. SSA, as a group, was less affected, with growth declining from 5.7% in 2008 to 3.7% in 2009 and rapidly bouncing back to 6.9% in 2010, according to the World Bank.

One would expect that a decline in world economic growth, especially economic growth in advanced economies, would be associated with a decline in net ODA and aid flows. That was indeed the case during this period. Whereas net total ODA and aid flows (from all bilateral and multilateral donors) to SSA increased from US$40 billion in 2008 to US$44 billion in 2009, it remained at this level in 2010.

As expected during the onset of COVID-19 in 2020, the world GDP growth rate contracted by -2.9%, with the growth rate in advanced economies contracting by a staggering -4.4%. SSA followed suit with a contraction of -1.6%. Despite the strong recovery in all three regions in 2021 (world GDP growth: 6%; advanced economies: 5.1%; SSA: 4.7%), slower GDP world growth of 3.2%, 2.4% for advanced economies and 3.6% for SSA was projected for 2022 due to the global destabilising effect of the Ukraine war.

African countries will need to be careful not to be the puppet between the three major powers

The 2020 total net ODA and aid flows, as well as the flows from OECD DAC member states, both showed increasing trends in 2020, mostly because the 2020 commitments were made before the external shock of the pandemic affected donor countries and multilateral organisations.

However, preliminary 2021 OECD data shows that the OECD DAC countries spent about 10.5% of their net ODA on COVID-19 controls such as prevention, treatment and care initiatives and vaccine donations. If the COVID-19 expenditure is considered, the preliminary US$33 billion flows from the OECD DAC member countries to SSA in 2021 imply that the non-COVID-related ODA flows to SSA remain stagnant on the 2020 level of US$29 billion. A similar stagnating trend could be expected in the 2021 total non-COVID bilateral and multilateral net ODA and aid flows to SSA from the 2020 level of around US$67 billion.

What could be expected of the future ODA and aid flows to SSA? Several major shifts and trends are going to determine the future of these flows over the next few years.

Bilateral donor flows to SSA may decline due to persisting lower-than-expected economic growth forecasts among OECD members. The past few World Economic Outlook forecasts of the International Monetary Fund each time further downgraded the economic growth projections of the world and those for advanced economies.

Concerning SSA, general humanitarian aid contributed to approximately 43% of the 2019 aid funding

Most of these donors are also experiencing monetary tightening associated with rapid rises in their inflation rates, and increases in government debt due to COVID-19 expenditure and stimulatory packages. Their own defence budgets (especially those of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation member states), military support for Ukraine, the energy crisis in especially Europe, and humanitarian support to neighbouring countries hosting Ukraine refugees have also affected their pockets.

While it was clear that the Millennium Development Goals redirected aid, a similar trend has been observed since the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were accepted in 2015. According to the OECD, net ODA has increased by 20% since the inception of the SDGs in 2015, partly due to the fact that the SDGs provide a clearer direction to the areas where aid is needed. Furthermore, the OECD DAC member countries formally committed themselves to contribute to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

However, indications are that the urgency and seriousness of the global climate challenges have contributed to a notable budget reallocation towards climate funding. This impact remains to be seen over the next few years.

Multilateral institutions have their unique challenges. They will need to focus on funding for the potential injection of estimates of over US$100 billion to restore infrastructure damaged by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as well as managing climate change issues and the world food crisis. But these institutions will also be under pressure to provide additional ODA and aid support to low-income countries.

Indications are that the urgency and seriousness of the global climate challenges have contributed to a notable budget reallocation towards climate funding

Concerning SSA, general humanitarian aid contributed to approximately 43% of the 2019 aid funding. Only 13% of aid went to debt relief, and indications are that this direction of funding is declining. Some other notable shifts are already evident. Early indications suggest that the fight against HIV/Aids, malaria and tuberculosis is significantly underfunded.

In line with the shift towards funding to alleviate the impact of climate change, some Just Energy Transition projects focusing on low-carbon emissions are funded in South Africa and Nigeria. In the context of other priorities, a decline in funding for debt relief may hamper available government revenue and ultimately poverty alleviation.

The current global uncertainty and instability will impact the ODA and aid flow to SSA in the next few years. Africa may not be a priority for bilateral donors only in the European Union and United Kingdom, but also in the United States, while they focus on more urgent global dilemmas playing out in other parts of the world.

At the recent United States (US)-Africa Summit in Washington DC, President Joe Biden mentioned that the US would prefer to increase foreign direct investment flows to African countries rather than aid. However, in support of the expected increase in debt of highly indebted countries, the United Nations pledged its members to increase their contributions in support of these countries.

The geopolitical tensions between Russia and its allies, China and the West may also affect aid flows to Africa, with especially the Russian government’s recent initiatives to obtain the support from African governments.

African countries will need to be careful not to be the puppet between these three major powers. Although the multilateral donor institutions will also be under pressure, the vulnerable countries in Africa will most probably be more dependent than before on their ODA and aid funds.

Elsabe Loots is a Professor in Economics at the University of Pretoria and specialises in development economics.

Image: © Jenny Matthews / Alamy Stock Photo