Exchange rate pressures take a toll on sub-Saharan Africa

International financial institutions could help ease exchange rate pressures and the associated shortage of foreign currency in the region.

Sub-Saharan African countries have been facing significant exchange rate pressures for over a year. Most currencies in the region have weakened significantly against the US dollar – the key currency for trade invoicing and external debt – with average depreciation of 16% between 1 January 2022 and 20 June 2023.

The depreciation of the official exchange rate exceeded 20% in Burundi, Ghana, Malawi, Nigeria, South Sudan and Sierra Leone during this period. This while Burundi, Ethiopia and Nigeria saw large spreads between the official exchange rate and the exchange rate traded in parallel markets for much of 2022. The exchange rate pressures also manifested in the depletion of international reserves as central banks supplied foreign exchange from their reserve buffers to finance imports and repay foreign debt.

The exchange rate pressures are largely driven by external developments. Interest rate hikes in advanced economies and greater global risk aversion decreased net foreign exchange flows into the region, as investors found it more profitable and less risky to invest outside.

Frontier economies were effectively shut out of global financial markets due to prohibitively high borrowing costs. Higher oil and food prices, partly due to the war in Ukraine, pushed up the import bill for net importers in 2022. Weak external demand, related to monetary policy tightening and economic slowdown in major economies like the euro area and China, weighed down on foreign exchange earnings through exports.

Countries where the exchange rate is pegged will have to adjust interest rates in line with the country of the peg

On the domestic side, large budget deficits kept the demand for foreign exchange elevated and contributed to the exchange rate pressures. About half of the countries in the region had deficits exceeding 5% of gross domestic product in 2022.

Weaker currencies have contributed to higher prices. About two-thirds of imports are invoiced in US dollars for the median country in the region, and when local currencies depreciate against the US dollar, consumers have to pay a higher price for these imports. Inflation was in double digits for about half the countries in the region by the end of February 2023.

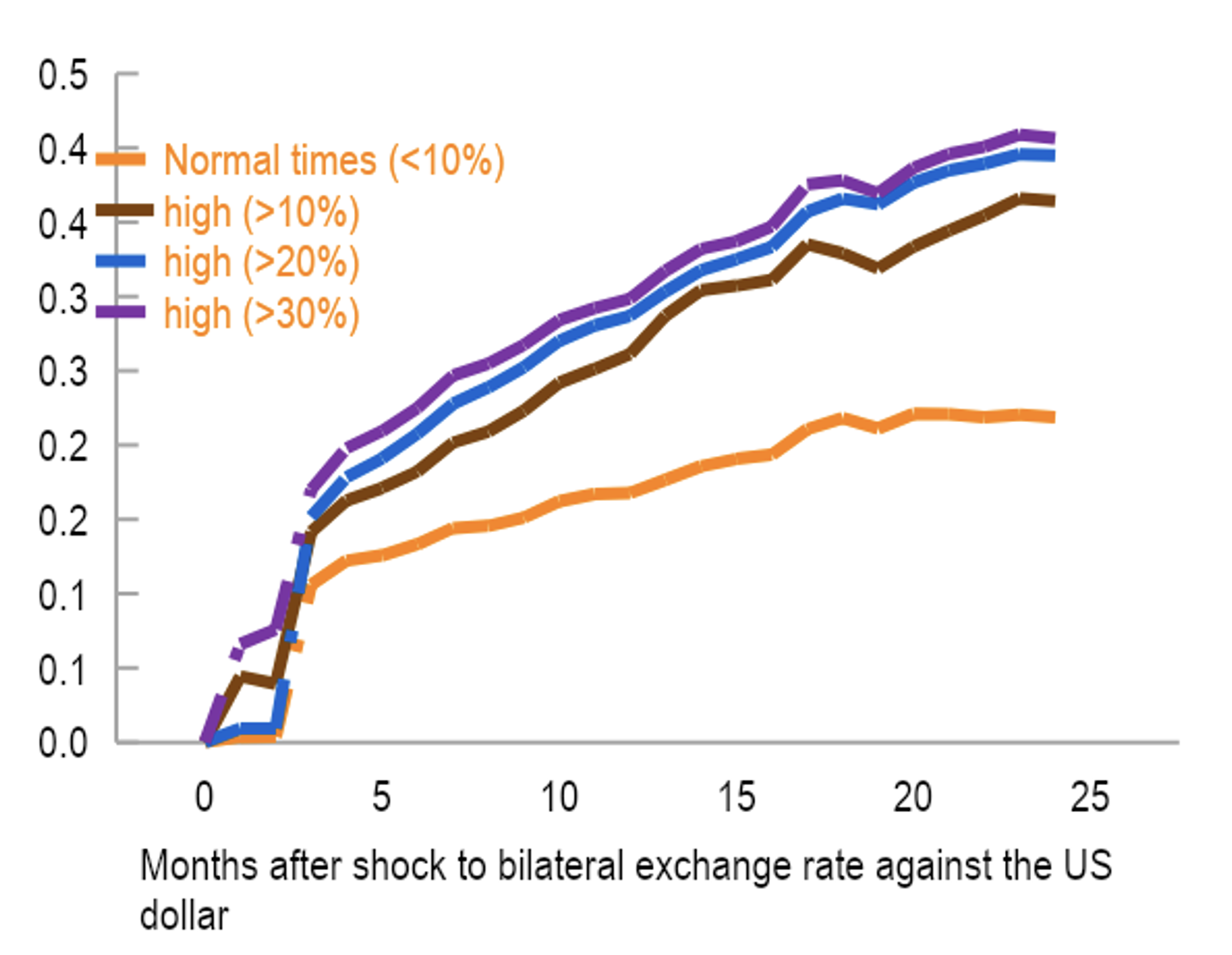

Our analysis shows that sub-Saharan African economies display a high exchange rate pass-through to inflation. A one percentage point increase in the rate of depreciation against the US dollar leads, on average, to an increase in inflation of 0.22 percentage point in a year, compared to 0.15 percentage point in emerging Asia and 0.18 percentage point in Latin America. The size of the depreciation also matters, with larger depreciations associated with larger and more persistent pass-through (Chart 1).

The exchange rate pass-through to inflation is asymmetric in the region. During episodes of depreciation, the pass-through to consumer prices is estimated to be eight times stronger than during periods of appreciation. This means inflationary pressures may not come down quickly when the local currencies strengthen against the US dollar.

Chart 1. Sub-Saharan African Countries with Non-Pegged Regimes: Exchange Rate Pass-Through to Inflation (percent)

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Note: The lines show – for different levels of exchange rate depreciation – the cumulative responses of inflation at different horizons after a 1 percentage point increase in exchange rate depreciation against the US dollar. The impact is estimated using local projection methods on monthly data for 44 sub-Saharan countries covering the period January 1980 to July 2022 while controlling for global food and energy prices, shipping costs, fertiliser prices, and climate-related shocks.

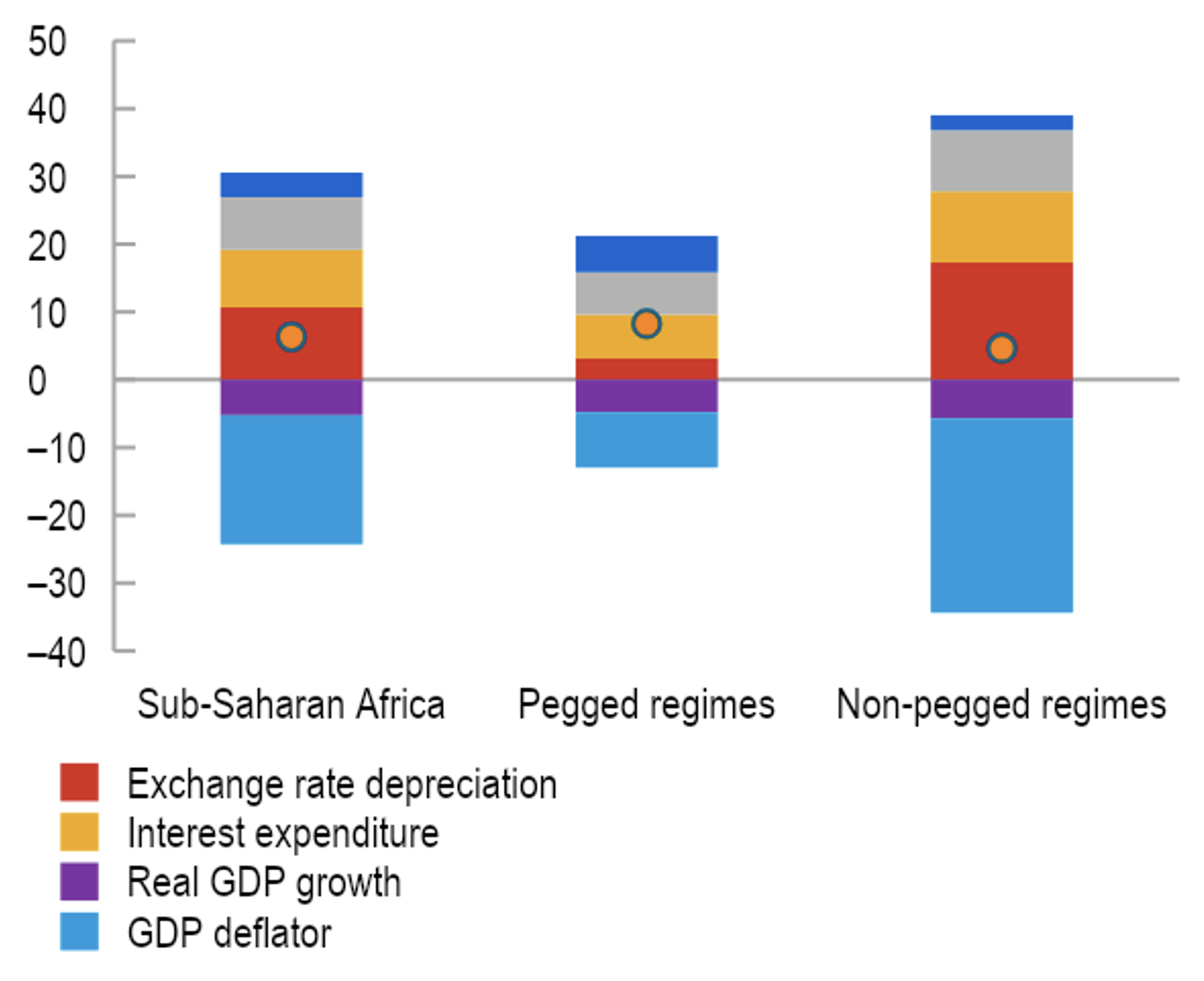

Weaker currencies also push up public debt. About 40% of public debt is external in sub-Saharan Africa and over 60% of that debt is in US dollars for most countries. Since the beginning of the pandemic, exchange rate depreciations have contributed to the region’s rise in public debt by about 10 percentage points of GDP on average by end-2022, holding all else equal (Chart 2). Growth and inflation helped to contain the public debt increase to about 6% of GDP during the same period.

Chart 2. Sub-Saharan Africa: Drivers of Changes in Public Debt Stock, 2019-22

(Cumulative change, percentage points of GDP)

Sources: IMF, World Economic Outlook database; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: For each debt driver, the bar represents its contribution to the change in debt between December 2019 and December 2022, had other drivers remained constant during this period.

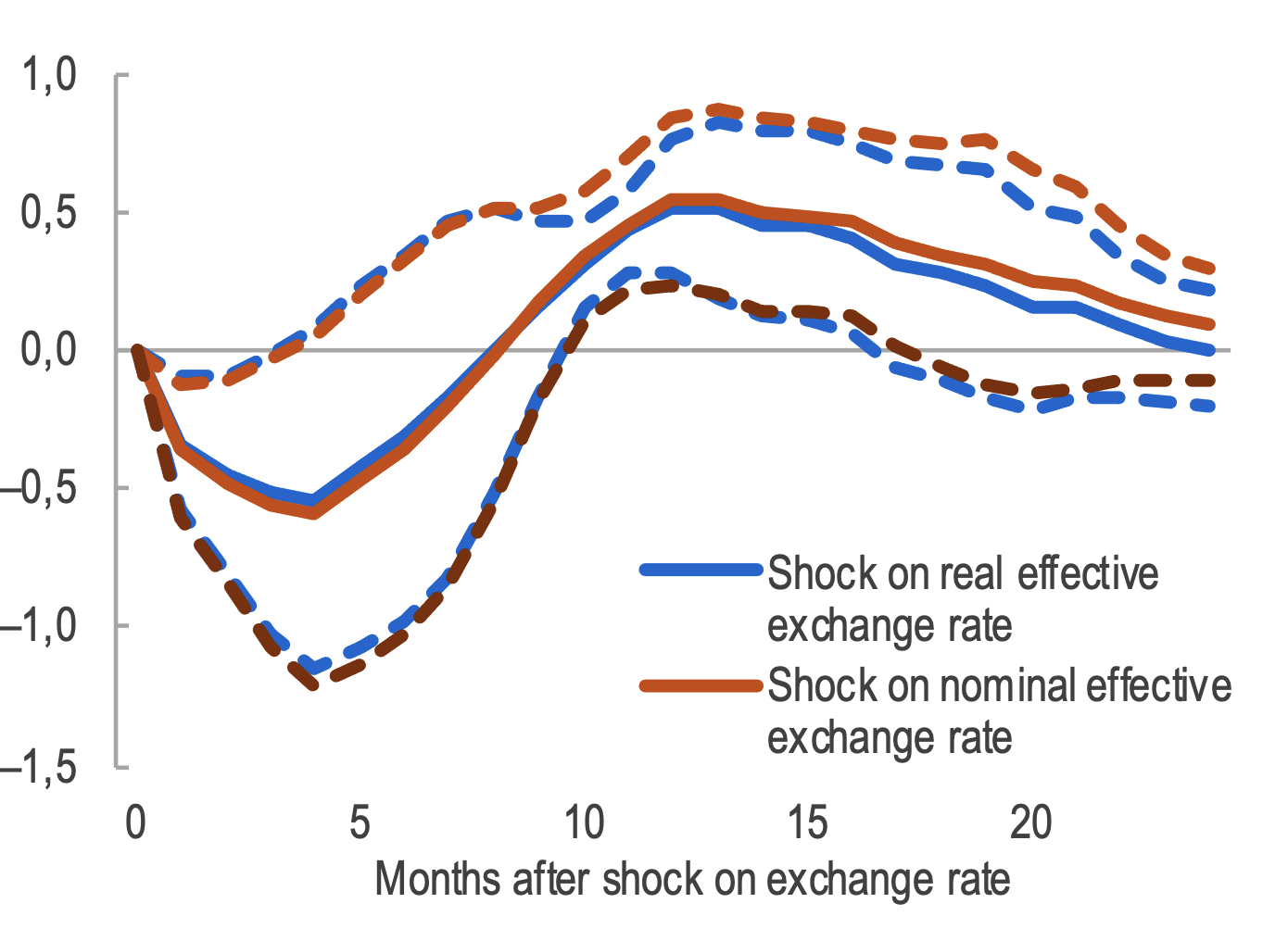

Exchange rate depreciation is associated with a deterioration of trade balance in the near term in the region (Chart 3). Trade is slow to respond to exchange rate depreciation as goods are invoiced mostly in US dollars and exporters require time to adjust their production despite higher profits while consumers face difficulties finding local substitutes for imports.

Financial conditions are expected to remain tight as central banks continue to fight stubbornly high inflation across the world

Over the medium term, the trade balance improves as countries adjust to new relative prices. However, this improvement is short-lived. This is likely due to structural impediments holding back export growth, together with the large share of commodities and agriculture products in the export basket, which tend to be less responsive to exchange rate changes.

Chart 3. Sub-Saharan Africa: J-Curve, Impact of Exchange Rate Depreciation on the Trade Balance

(Impact on difference between log of exports and log of imports)

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Note: The red (blue) bold line represents the cumulative impact of the nominal (real) effective exchange rate depreciation of 1% on the difference of the log of exports and log of imports, estimated using local projection methods controlling for commodity prices, shipment costs, and output (both domestic and of trade partners) proxied by the night light indicators. The NEER specification also controls for the change in relative consumer prices. The dotted lines show the 90% confidence interval. The sample spans January 2013 to June 2022 for 39 countries. Given that imports exceed exports for the median country, estimation results can be interpreted as showing the effect on the trade balance.

Most countries in the region tightened monetary policy to fight inflation. This helped to ease exchange rate pressures. However, many countries also resisted currency depreciation by intervening in the foreign exchange market.

Sub-Saharan African countries have been facing significant exchange rate pressures for over a year

Administrative measures such as multiple currency practices and other forms of foreign exchange rationing were also used to manage foreign exchange demand. These measures can be highly distortive and may lead to corruption. Moreover, they may not work very well in stemming inflation, as parallel markets for foreign exchange may emerge and local prices will typically adjust to the exchange rate in these markets.

Financial conditions are expected to remain tight as central banks continue to fight stubbornly high inflation across the world. Commodity prices may also remain elevated for long. Against this backdrop and with reserves running low, countries where the exchange rate is not pegged (fixed) to another currency have little choice but to let the exchange rate adjust. This, in turn, can nudge consumers towards more locally produced goods and investors towards exports, and help the economies adjust to the new external environment.

However, complementary policies are needed to offset the adverse effects of depreciation. Tighter monetary policy can help to anchor inflation expectations. Fiscal adjustments will help to keep debt sustainable and rein in external imbalances, particularly in countries where fiscal imbalances are the main drivers of exchange rate pressures. At the same time, targeted support to the poor who are adversely affected by rising prices may be needed.

About 40% of public debt is external in sub-Saharan Africa and over 60% of that debt is in US dollars for most countries

Countries where the exchange rate is pegged will have to adjust interest rates in line with the country of the peg. In the absence of exchange rate flexibility, they may have to rely more heavily on fiscal adjustments to stabilise their reserve positions.

In both sets of countries, the use of distortive administrative measures should be minimised. Support from international financial institutions (including the International Monetary Fund) could help ease exchange rate pressures and the associated shortage of foreign currency.

This blog is based on the analytical note: Managing Exchange Rate Pressures in Sub Saharan Africa – Adapting to New Realities.

Image: © Iryna Veklich / Alamy Stock Photo