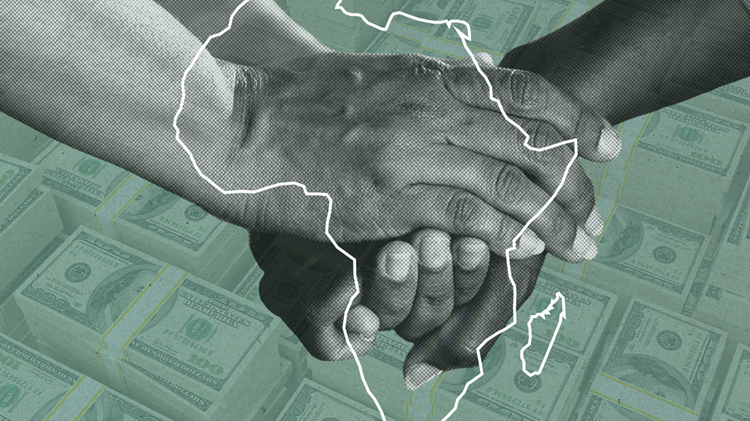

Despite the hiccups, African peace mission was a success

In spite of the apparent disdain with which Russian President Vladimir Putin treated the African delegation on the weekend, South Africa has managed to elevate its international and African stature, argues Jakkie Cilliers.

There are many ways to view the African peace mission to Ukraine and Russia. Was its timing appropriate? Is it likely to have any impact? Was it a fruitful trip, a waste of time, or an effort by South Africa to save face (especially in the light of push-back from the West on its position)? The logistic and practical issues aside, it was pretty successful and meaningful.

First, it is essential to situate the mission within the context of the upcoming July 2023 AU-Russia summit in St Petersburg. Without the peace process, that summit next month is in jeopardy, which is not in South Africa's interest, being the only African member of BRICS. Now South Africa and other Africans can attend and argue that the parallel peace effort demonstrates the importance of ongoing engagement with Russia, which is not, in this view, an international pariah.

Previously African concerns about the unintended consequences of Russia's invasion played a role in convincing Vladimir Putin to agree to the Black Sea initiative to allow grain exports from Ukraine, including to Africa. It cost Russia nothing, and Putin could appear sensitive to globally negative perceptions regarding the fallout of the war.

With a budding peace process, irrespective of the fact that there is no current prospect of a ceasefire or negotiated settlement, South Africa and others can argue that there is no reason to boycott a summit with Russia next month. Russia still has some friends in Africa and a proven ability to inflict considerable damage on the continent, evident in Mali and Sudan. Through Wagner and arms, Russia offers options to one of Africa's most enduring challenges that support from the United Nations, France, the UK, and others have been unable to resolve through traditional peacekeeping, namely instability.

At the Institute for Security Studies, we recently completed a set of global scenarios ranging from a Sustainable World to a World at War to examine Africa's place in a changing world and how best to ensure growth and development. The findings are clear: Russia has violated the UN Charter, regularly targets civilians as part of its military strategy and threatens the use of nuclear weapons, and should be condemned on that basis. But choosing unyielding sides in this war, or indeed on many matters such as privacy, and ICT service providers (such as Huawei), is not in Africa's interests.

Africa's overriding foreign policy purpose is an international context that facilitates its development. That requires global stability and the freedom to trade and engage with the US, Europe, China, India and the global south.

Great power competition is bad for Africa, aka we need the war to end, no matter on whose terms. Russian aggression and Western efforts to counter it divert attention, resources and trade. It depresses global growth, pushes up inflation and constrains foreign direct investment globally, which is all bad news for highly indebted countries hungry for capital.

Impact of war on Africa's development prospects

The war damages Africa's development prospects. It will undermine the space to focus on much more important matters for the continent, such as reform of the international financial architecture, membership of the G20, UN Security Council reform and the arrangements for the 2024 UN Summit of the Future, never mind its impact on efforts to deal with carbon emissions and climate change.

Not all of this relates to Russia-Ukraine, of course. But many in the West tend to collapse evil Russia and bad China into a single envelope while they should be dealt with separately. The tension between China and the US has spilt into Africa with hugely adverse effects, all accentuated by the war in Ukraine. Africans must ensure it does not serve as a proxy battlefield for others again.

The penny has dropped with the recent references to derisking (not decoupling) and the resumption of high-level visits (such as that by Secretary of State Blinken to China).

The second matter, closer to home, is Putin's attendance at the BRICS summit in South Africa later this year. BRICS is a big deal for South Africa. This year we host an apex meeting of a club representing a quarter of global GDP and almost 60% of the world's population, with both numbers set to increase.

South Africa is a small pebble in BRICS, but we play in the big league through it. The ANC is ideologically deeply committed to a post-Western international order and believes BRICS, not the G7 grouping, to be the future. Succumbing to Western pressure on BRICS contradicts the ANC's deep-seated anti-Westernism and its antipathy against the US. By playing footsy with Russia, South Africa confirms that it is not a fair-weather friend unwilling to bite the bullet when times are tough, but deeply committed to a post-Western global order.

The bottom line for South Africa is to demonstrate that it has stood by its BRICS allies and tried every avenue to allow Putin to visit. If the South African government cannot legally guarantee his safety, he will not come.

Deeply divided

Domestically, the debate around the summit has exposed the extent to which the country is still deeply divided on many issues. The business community looks westward, and the ANC to Russia, China and Cuba, which some see as also reflecting racial divisions, although the reality is more complex. It has exposed an awkward and unwieldy foreign policy that contradicts our current trade interests and, to many, affirms a government unable to communicate or able to avoid being instrumentalised by a much more nimble Russia, in particular.

At home, the kerfuffle around the lack of clearance for all the persons on the flights and the boxes of arms merely reaffirms the well-established incompetence of the government and the ongoing damage wrought by cadre deployment and affirmative action. Major General Wally Rhoode is not a career police officer, but parachuted into senior rank without attending SAPS school, and the lack of adherence to procedures and legal requirements is simply embarrassing, as it was with the Phala Phala farm robbery saga.

Poland did not try and politically frustrate the African peace mission. They simply did what Home Affairs does regularly - insist on administrative minutia to discourage requests for work permits, visas and other travel documentation until the hapless applicant just gives us and goes home. The South African standard response, crying racism, is hardly credible when a head of state visit is involved in something as important as Europe's largest war in more than half a century.

In considering Rhoode, I was reminded of an incident many years ago, when we enthused about the importance of black economic empowerment in the military. A recently retired African-American air force major general that we had brought over from the US to inform the debate looked at me quizically before dryly remarking that, in his experience, "it took about 20 years to get 20 years of experience".

The embarrassment around the lack of approval for arms imports and correct lists of passengers should remind all South Africans of the damage that cadre deployment does.

A ceasefire and eventually peace will come to Ukraine, but later. It becomes possible when the Ukrainian counter-offensive has run its course, Russia has counter-attacked, and the exhausted armies are genuinely bogged down with no prospect of advancement by either. That takes us to the European winter in several months and beyond. There may, of course, be a spectacular collapse of Russian or Ukrainian armed forces in the field that changes the calculations on either side. Who knows.

Wind is behind Ukraine

Currently, the wind is behind the sail of Ukraine, which is trained and equipped with sophisticated Western armaments. But time is on Russia's side, and the winds may shift.

Putin is banking on a positive turn in the US elections. Should Donald Trump return to the Oval Office, his unpredictability could see the US abruptly terminate or reduce arms support to Ukraine early in 2025. Europe will not be able to fill the gap, and Ukraine will be left exposed.

By implication, Putin will do everything in his power to ensure a favourable outcome of the 2024 US presidential elections and will first want to see where the results go, meaning it is unlikely that the start to an end to the war in Ukraine is in sight before the end of 2024.

Even then, Africa will have put down a marker that it, too, has an interest and affirmed the importance and relevance of its 54 members. Despite the apparent disdain with which Putin treated the African delegation, South Africa has also elevated its international and African stature. Not bad for someone who is generally perceived as a failure as president.

This was first published by News24

Image: Twitter/PresidencyZA