The West and China in Africa’s development future

To avoid a new era of bipolarity, this time on steroids, the two need to find a way to reset relations.

What is the impact of alternative global futures on Africa, the continent with the largest and most complex development challenges worldwide? In a new report launched on 18 October, the African Futures and Innovation team at the Institute for Security Studies unpacks four alternative pathways for Africa and their implications for development.

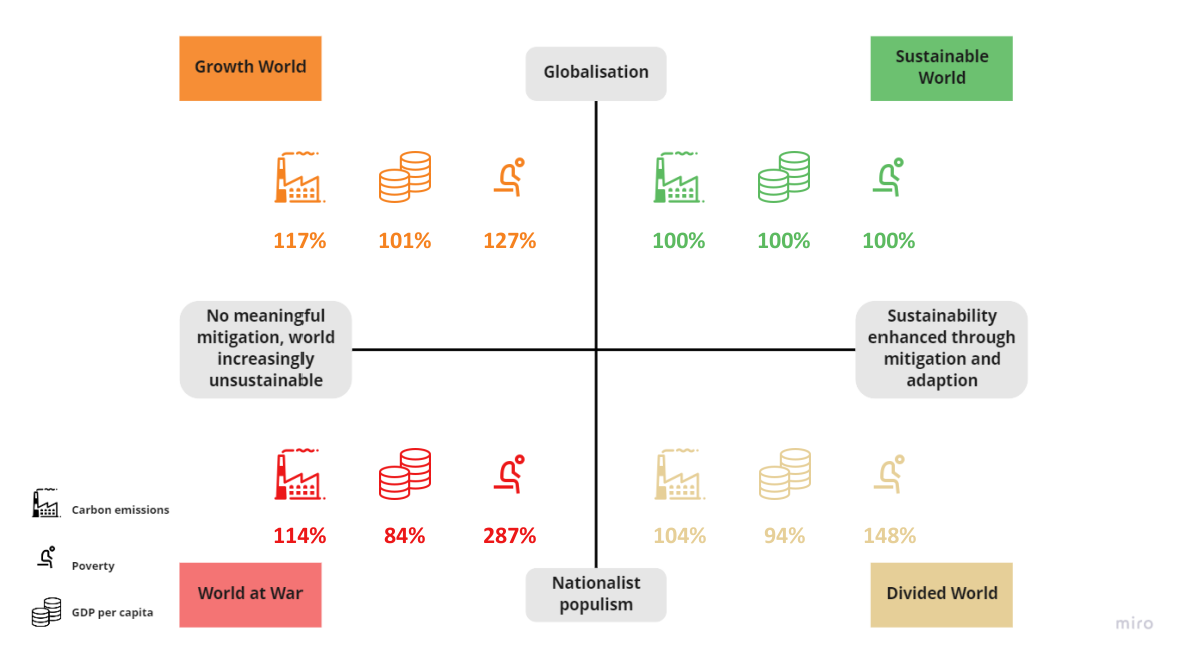

The report presents and models four futures – a Sustainable World, a Divided World, a World at War and a Growth World. It uses two dimensions to frame the analysis: the extent of globalisation or nationalist populism along one axis, and the extent of climate change mitigation and adaptation, or lack thereof, on the other.

Compared to the Sustainable World, the current trajectory towards a Divided World means Africa will release 4% more carbon, gross domestic product per capita will be 6% lower, and extreme poverty 48% higher by 2043. This is the time horizon we have adopted for our forecasts.

Chart 1: Comparing scenario impact on carbon emissions, GDP per capita and extreme poverty in Africa

The scenario analysis starts by reviewing the likely distribution of power globally, using various indices embedded in the International Futures forecasting platform hosted and developed by the Frederick S Pardee Centre for International Futures at the University of Denver.

Our analysis confirms that China will overtake the United States (US) as the most powerful country in the world by mid-century. The West, comprising the US and the European Union, cannot constrain China’s momentum towards great power status.

The current trajectory towards a Divided World means extreme poverty in Africa will be 48% higher by 2043

Still, the West will continue to dominate globally and maintain a technological and wealth advantage even over a possible Chinese-Russian axis. However, that depends on the relations between the two major Atlantic powers.

Nothing is pre-ordained, of course, and numerous unlikely but high-impact changes could disrupt this broad structural trend. The first is a great power implosion affecting the US, China or the European Union. However, in the case of the EU, the reverse could also occur, such as expansion to include Turkey and a democratic Russia.

Deeper regional integration in Asia could make it the largest and most influential global political and economic bloc, but would require an end to the divisions between India, China and Japan, among others.

Ironically, the greatest threat to China’s ongoing rise is potential democratisation as domestic incomes breach levels that elsewhere have unlocked a push towards individual actualisation and, eventually, democratisation. Such change would probably disrupt China’s current growth trajectory and negatively affect Africa, given China’s importance as a trading partner, investor and infrastructure builder.

The priority for Africa is to maximise its sustainable development prospects

Alternatively, and less likely, the ongoing divisions in the US could, if left unchecked, result in domestic violence and armed conflict. Either development would leave the other as globally dominant.

But the most likely disrupter is the accelerated impact of climate change that could force a reassessment of the current global trajectory towards a Divided World and provide an impetus towards a collective response.

The future relations between the US and EU are therefore important for the continued dominance of the West, while the orientation of India will also affect the future global balance of power and the nature of that order.

A united West will dominate globally but not if the US and EU bicker and go their separate ways. This is likely under the resumption of the disastrous foreign policies of Donald Trump should he be re-elected as US president in 2024. In addition, although the war in Ukraine has strengthened relations in the EU, and between the US and EU, rising energy prices coupled with a likely recession will strain EU unity.

Meanwhile the Ukrainian conflict and the fear of China’s rising influence are having significant collateral damage effects. We argue that the West needs to differentiate between China and Russia and resist simplistic narratives that pit a benevolent West against bad China associated with evil Russia in Africa. For Africa to develop and reduce poverty it needs China, the EU and the US. It cannot choose one above the other.

Not all African leaders are committed to the development of their countries

The Chinese Communist Party won’t abandon its collectivist views on politics and development just as democratic countries won’t abandon a belief in individual freedoms and political rights. What is needed is a determined effort to rebuild relations between the West and China to one of mutual respect and acknowledgement of the differences in approaches to development and governance. Such a rapprochement would be a crucial step towards the achievement of a Sustainable World that allows space for Africa’s development.

But it’s important to underline that not all African leaders are committed to the development of their countries. Some rule in the interests of a particular clique, family or ethnic group, and in others state capacity is so weak it renders governing impotent.

Efforts to include countries in the Sahel, some military governments in West Africa, countries such as Sudan, South Sudan, and family businesses like Eswatini and Equatorial Guinea, cannot currently be part of an African journey of renewal.

Practically, African leaders must be bold enough to embark on a two-speed approach where some countries commit earlier to higher governance standards and demonstrate the associated advantages. Others can join later.

The obstacles to such an approach are immense, given the priority the African Union (AU) places on continental unity and the emotional appeal of pan-Africanism. Every previous effort to such a two-speed approach has failed – for example, the Conference on Security, Stability, Development and Cooperation in Africa. Or it eventually includes all countries, such as the New Partnership for Africa’s Development and the African Peer Review Mechanism.

All of these started as initiatives that would require minimum entry requirements. The idea of ‘leaving no country behind’ is appealing but cannot serve as a practical basis to advance Africa’s development.

Continuing with current practices of lowest-common-denominator politics at the AU level, seeking to take all of Africa’s diverse countries along the development journey at the same speed, won’t disrupt Africa’s current low growth trajectory. It effectively penalises those more stable countries that have more predictable policies and better governance.

The priority for Africa is to maximise its sustainable development prospects through greater policy convergence among these first-tier countries and stronger, more effective institutions and the evolution of a next-generation rules-based global system. An authoritative approach, where key African countries set standards for foreign investment, insist on full transparency and resist political conditionality rather than trying to take the entire continent along, is crucial.

Finally, if the West is to retain influence and assist Africa, it must find ways to de-risk investment in the continent, while Africans need to work much harder to reduce policy volatility and improve domestic stability. Europe, the US and Africa need ongoing engagement, communication and greater visibility of Africa’s development prospects.

But most important if we are to avoid a new era of bipolarity, this time on steroids, the West and China need to find a way to reset relations.