Africa's rise in protests is about more than macroeconomics

Like the rest of the world, the continent has seen public discontent growing even as wealth has improved.

Public discontent, defined as the collective feeling of frustration and unmet expectations, has risen globally, despite improvements in overall wealth. The same is true for Africa.

Between 1990 and 2019, gross domestic product (GDP) and per capita income climbed steadily on the continent, and extreme poverty declined significantly across many countries. Numerous human development indicators improved, and overall living standards showed an upward trend.

Yet in this period, discontent expressed through protests and riots in Africa increased. According to a recent Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development study, this paradox can be explained by the disparate distribution of resources, widening inequality and systemic relative deprivation among various groups of people. COVID-19 has exacerbated these hardships and frustrations.

Economic factors are central to understanding the causes and consequences of discontent. But such growth alone doesn’t deliver overall citizen well-being or provide an antidote to unrest. Political uncertainties, poor service provision and the absence of basic freedoms can overrule economic indicators.

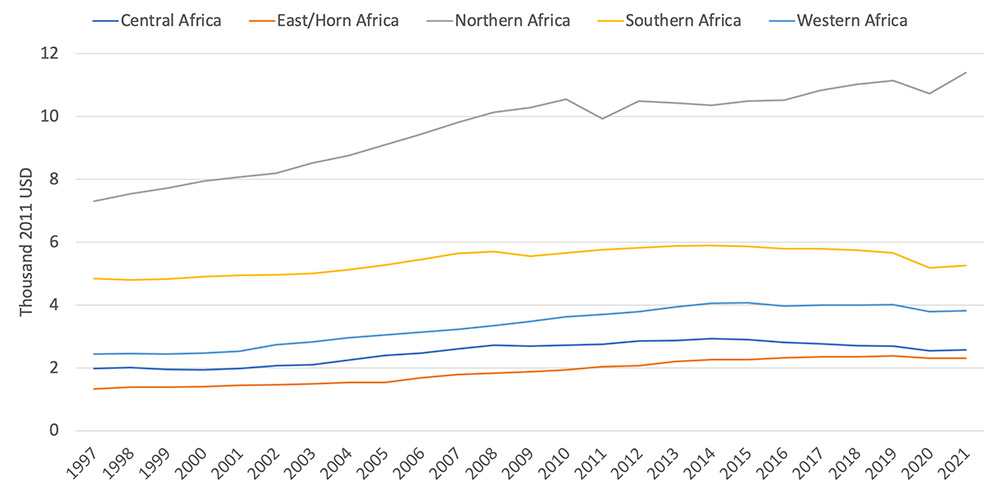

Despite the greatest increases in income-related well-being, North Africa had the most protests in Africa.

Discontent can also manifest in ways other than public unrest – for example low levels of civic participation such as voter turnout. Dissatisfaction of this kind builds gradually until an incident sparks generalised violence or a revolution, as seen in Tunisia and Burkina Faso.

On the continent, North Africa is the most developed region. It has an estimated average per capita income of US$11 390 in 2021, between US$6 000 and US$9 100 more than Central, East/Horn and West Africa, with the East/Horn region being the least developed.

Chart 1: GDP per capita in African regions

Source: IFs v7.63, historical data from WDI, IMF

But despite North Africa seeing the greatest improvements in wealth- and income-related well-being, the region had the most protests and riots on the continent in the past decade, according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project. In fact, in the years leading up to the 2010 Arab Spring, per capita income was on a steep upward trajectory (Chart 1).

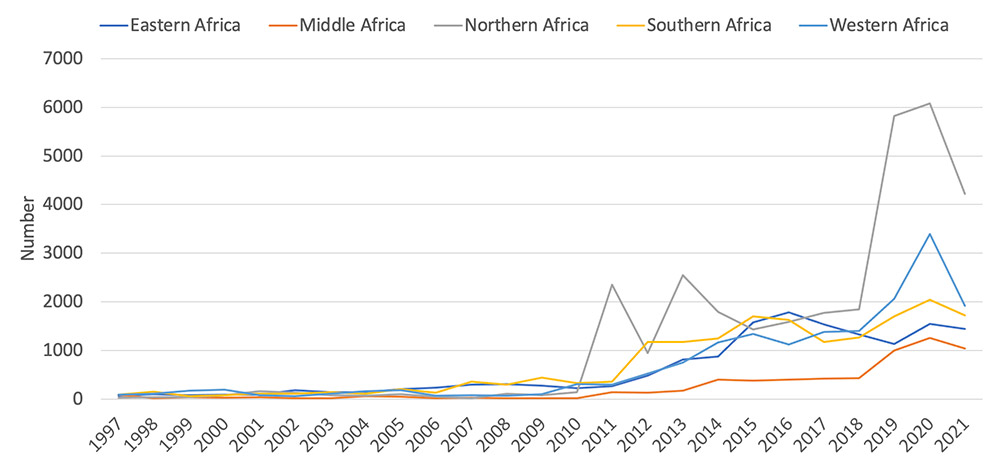

However, Africa’s other regions started experiencing an upsurge of protests and riots from 2007/8 during the global financial crunch. Chart 1 shows that GDP per capita, although improving, was quite modest. Southern Africa had the least progress in this regard and the most pronounced spike in protests and riots. The sharp rise in protests and riots in 2020 (see Chart 2) can be attributed to frustrations and vulnerabilities linked to COVID-19.

Chart 2: Protests and riots in African regions, 1997–2020

Source: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project

These trends expose the relative variation in the sources of discontent and the limitations of using GDP per capita as the cornerstone of measuring well-being.

In Southern Africa and South Africa specifically, structural challenges stemming from apartheid and the failure of successive governments to expand essential services are key factors in analysing discontent. This complexity is exemplified by the fact that South Africa is the most unequal country globally.

The sense of relative and absolute deprivation among people over long periods without tangible improvements has caused frustration to boil over. The riots and looting in July in South Africa can partly be understood through this lens.

In North Africa, the state-led model of development characterising governance in the region has produced impressive human development outcomes in education and healthcare over the past five decades. But despite relatively good basic service delivery, the authorities were at loggerheads with their people, whose needs had evolved. The public demanded greater political, civil and economic freedom, fuelling the Arab Spring.

An important question is whether protests have brought change that can lessen the discontent that fuelled them in the first place. The simple answer is yes – although the change isn’t always the desired kind, and the trajectory isn’t always linear.

Since the Arab Spring, Tunisia has been the only country that has transitioned to democracy. Even so, people’s expectations remain unmet because the new democracy is more electoral than substantive and real institutional reform is yet to happen. Algeria and Egypt experienced some reforms but have backslid, and Libya has fallen into civil strife.

Sustainable development isn't just about economics – it demands new ways to build more inclusive societies.

However, in many countries, protests have instigated the democratisation process, created space for civil society activism, and improved human rights. Evidence shows that protests seek to redress discrimination, exclusion, injustice and exploitation, which all arise from denials and violations of human rights.

In several Southern African countries, discontent has inspired protests and civic engagement that have delivered political change and helped fight corruption and hold governments accountable. These achievements do however need to be accompanied by measures to improve the distribution of economic gains.

Sustainable development isn’t just about sound macroeconomic indicators such as GDP and per capita income. It involves social, political and economic factors and demands innovative ways to build more inclusive societies. This is particularly true for Africa amid weakened public finances, rising inequality and poverty in the wake of COVID-19.

Building trust and strengthening civic institutions to create a sense of collective responsibility is crucial to nurturing a strong society. It provides channels for people to articulate their grievances and renew the bonds between governments and the people.

Economically, it’s important to restructure and create greater inclusion across societies. Decentralised approaches to development that meet local needs should be encouraged. A focus on supporting vulnerable households could increase people’s capacity to participate in beneficial economic activities.

To achieve this, development strategies should capitalise on a country’s comparative advantage. More public-private collaborations for increased financing and a sense of ownership must be harnessed.

Watch the video recording of the ISS–OECD seminar ‘Protest as a force for change: Africa’s role in global trends’, here.

This article was first published by ISS Today.