Unveiling Potential: Boosting Inclusive Growth and Development in Mozambique

Summary

Mozambique, situated in Southern Africa and bordered by six countries, is rich in mineral reserves, arable land, and a coastline. After achieving independence in 1975 and ending a 15-year civil war in 1992, Mozambique began to experience socio-economic progress. Between 1993 and 2015, it was one of Africa’s fastest-growing economies, with an average annual growth rate of about 8%. This growth was driven by factors such as political and macroeconomic stability, a rebound in post-war economic activity, increased Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in extractive industries, and post-war reconstruction efforts. This rapid economic growth improved life expectancy, reduced mortality rates, and expanded access to education, water, and electricity.

However, these high growth rates were not inclusive enough and not accompanied by a structural transformation of the economy. The country remains one of the poorest globally, with a GDP per capita of about US$450 in 2023 and high levels of poverty and inequality. Post-2015 growth slowed to an average of about 3% due to various challenges including the "hidden debt" scandal, insurgencies, natural disasters and the COVID-19 pandemic. The Government of Mozambique faces the urgent task of achieving sustainable and inclusive growth, with hopes pinned on gas megaprojects. However, past experiences in Africa indicate that natural resource extraction does not always lead to desired outcomes. Therefore, achieving meaningful growth requires strategic leadership and investment in sustainable development.

The Mozambique National Development Strategy 2023-2043 seeks to address these challenges through economic diversification and infrastructure improvement. The discovery of 150 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in 2010 holds the potential for an economic boost, yet revenue projections are uncertain due to volatile markets. Additionally, the country’s informal economy, with 96% of the workforce in 2021, hinders development and reduces government revenue. By 2022, 71% of the population lived in extreme poverty, affecting 23 million people.

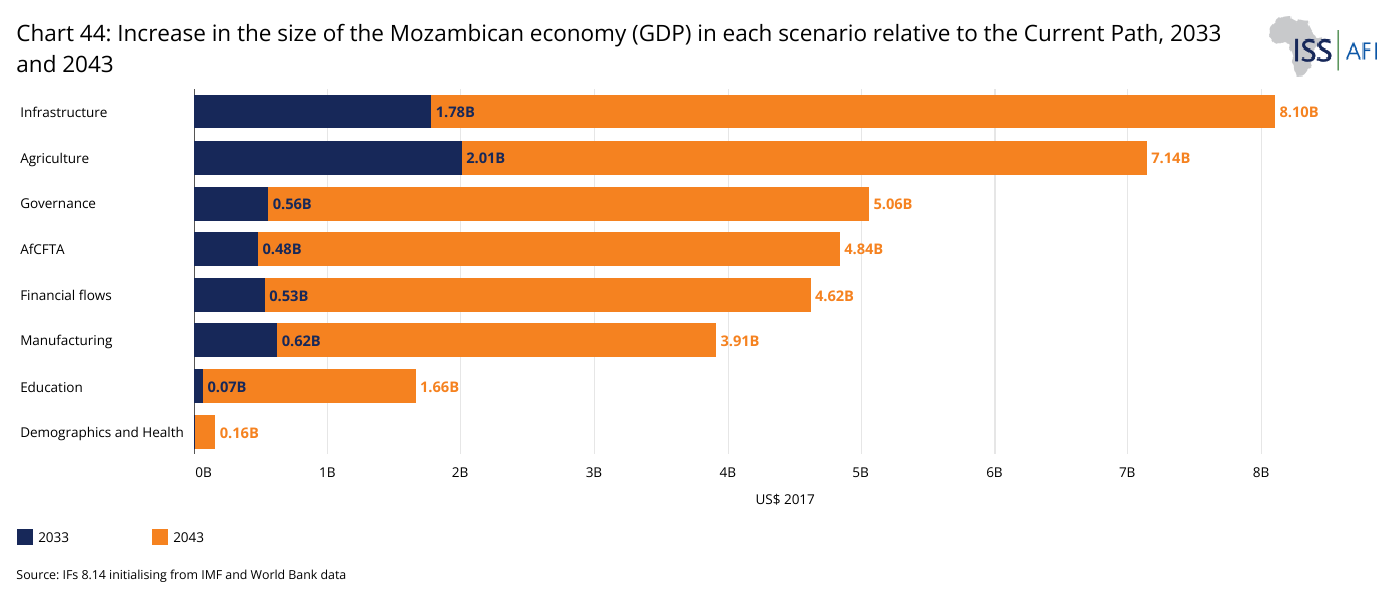

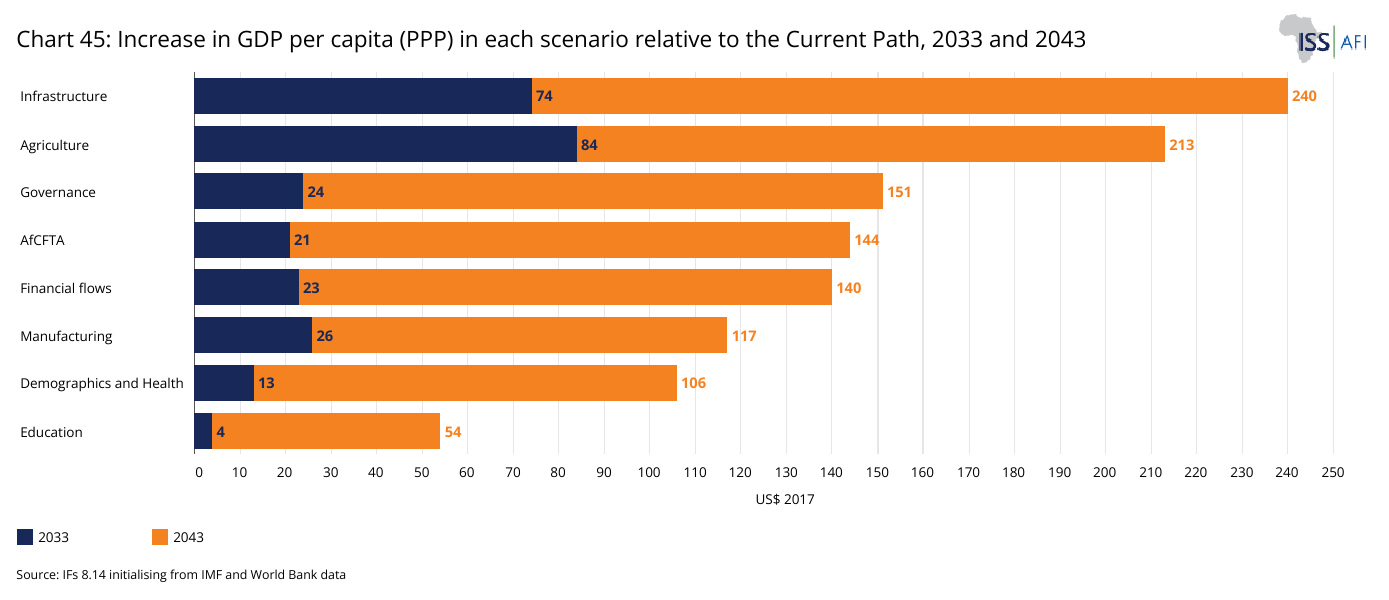

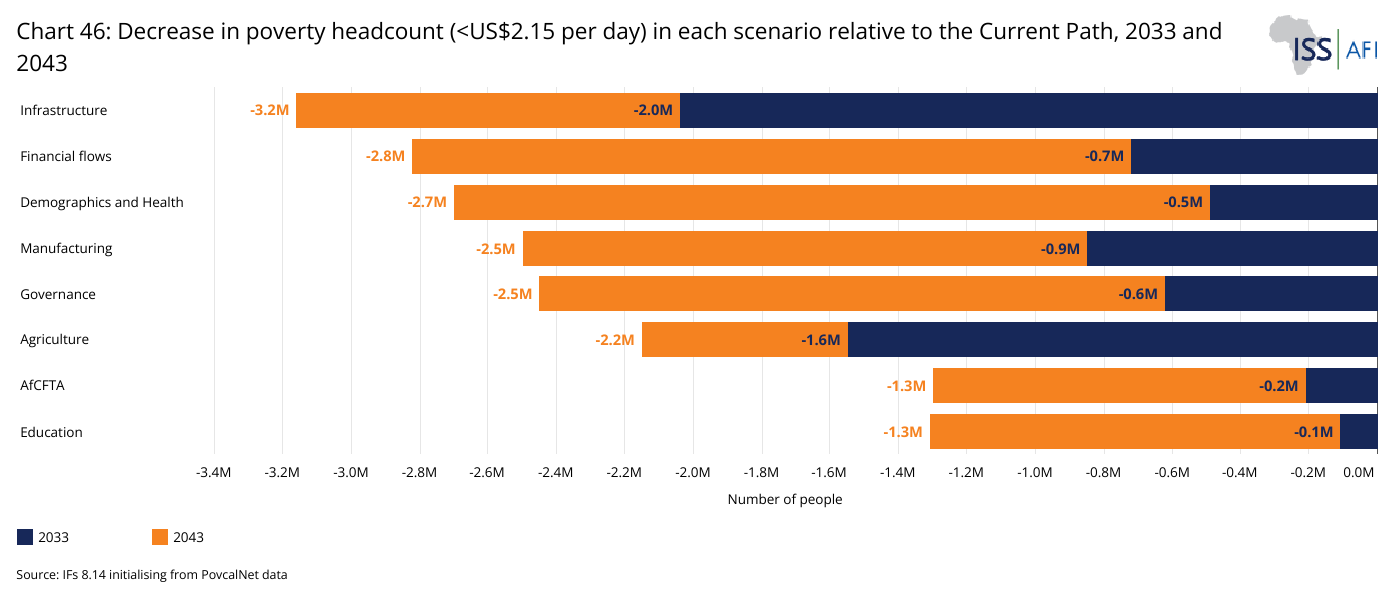

An analysis using the International Futures forecasting tool suggests that Mozambique is likely to miss most of its development targets by 2043 under current trajectories due to governance issues, infrastructure bottlenecks, low agricultural productivity and limited economic diversification. The sectoral scenario analysis, which models ambitious but realistic policy interventions across eight sectors (agriculture, education, governance, infrastructure, health and demographics, financial flows, manufacturing and trade), shows that the Infrastructure scenario will have the most significant impact on Mozambique’s GDP growth by 2043, followed by the Agriculture, Governance and Free Trade (AfCFTA) scenarios. In reducing extreme poverty, it will be the Infrastructure scenario followed by the Financial Flows, Manufacturing and Governance scenarios. In the short-to-medium term (i.e., up to 2035), Agriculture has the biggest impact on GDP. Infrastructure development and the Agriculture scenario will have the most significant impact on poverty reduction compared to other scenarios.

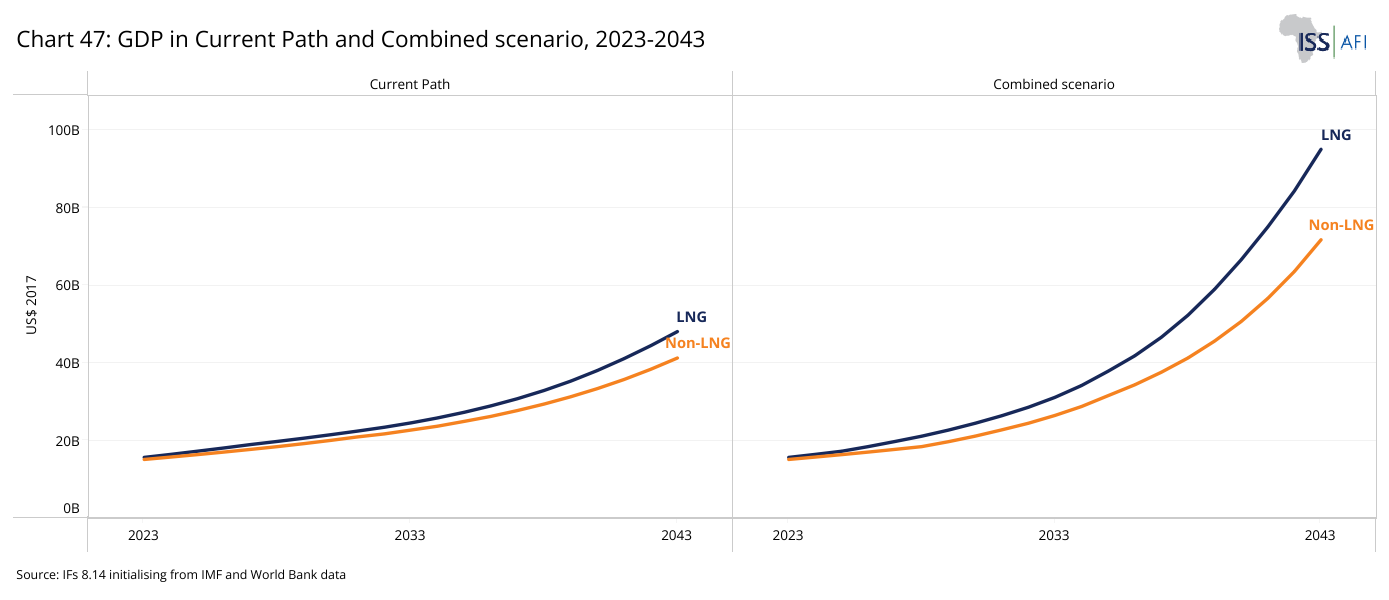

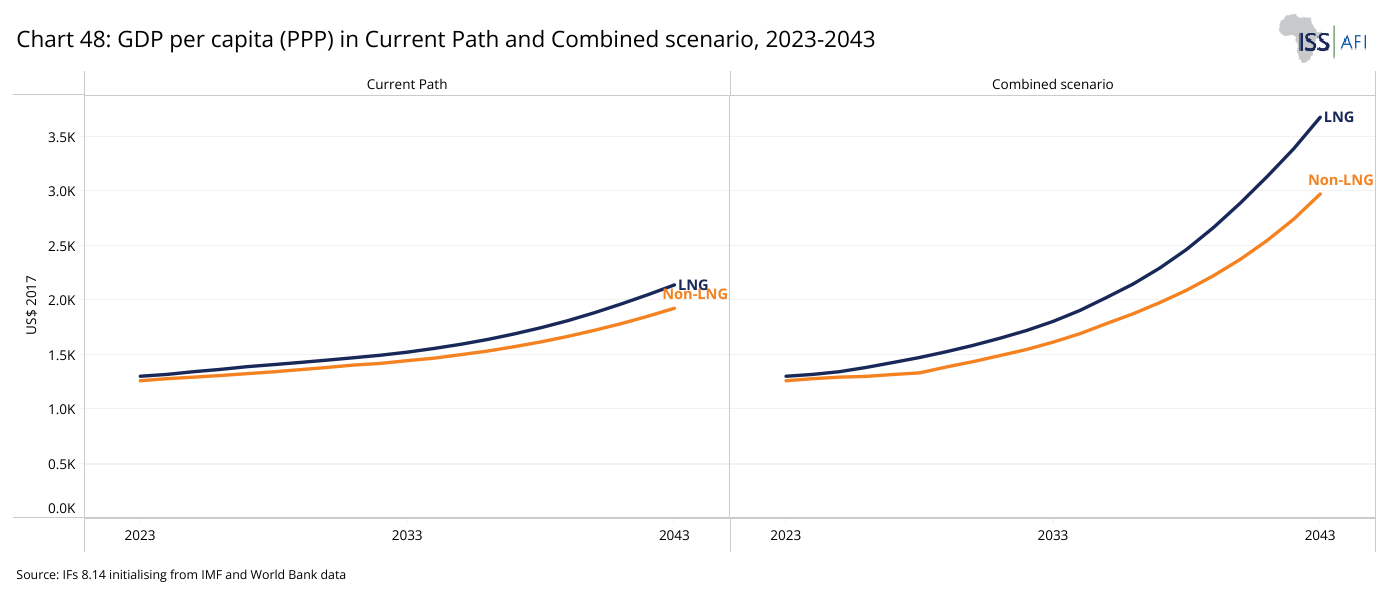

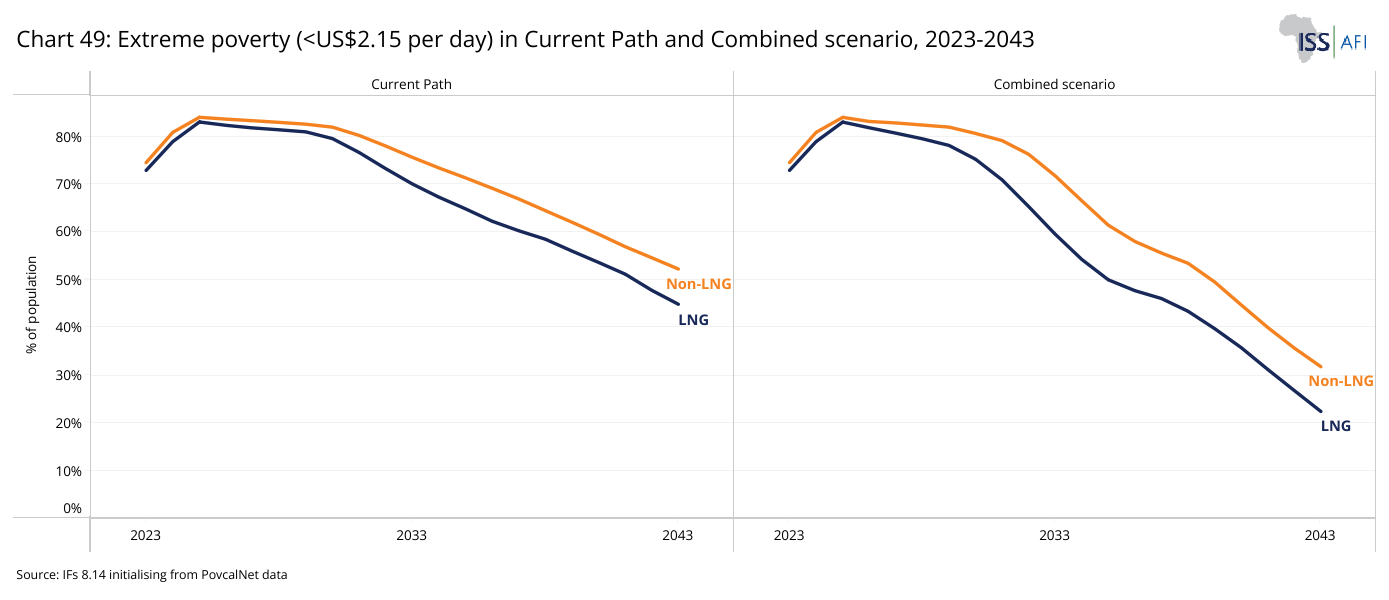

The findings underscore that no single scenario is a panacea for achieving meaningful inclusive growth by 2043. All scenarios boost GDP, with Infrastructure having the most significant impact. A comprehensive effort to improve outcomes across all these sectors will help set the country on a track toward inclusive growth and development. The integrated development push across all the above sectors (the Combined scenario) offers the most substantial improvements. It will result in an economy (GDP) that is US$47 billion larger than the Current Path forecast in 2043. GDP per capita (purchasing power parity) will be US$1 536 larger than what it would be on the Current Path in 2043. The poverty rate at US$2.15 is 22.4% in 2043 instead of 44.9% on the Current Path in the same year. This Combined scenario demands strong political commitment and wise investment of natural gas revenues for sustainable, inclusive growth.

The study recommends ambitious yet feasible policy interventions across all sectors and highlights the importance of mitigating natural disaster risks and climate change impacts. Overall, the study emphasises the need for comprehensive, strategic leadership and investment in sustainable development to achieve meaningful growth. By addressing governance issues, enhancing infrastructure, improving agricultural productivity and diversifying the economy, Mozambique can set a path towards inclusive and sustainable development.

All charts for Unveiling Potential: Boosting Inclusive Growth and Development in Mozambique

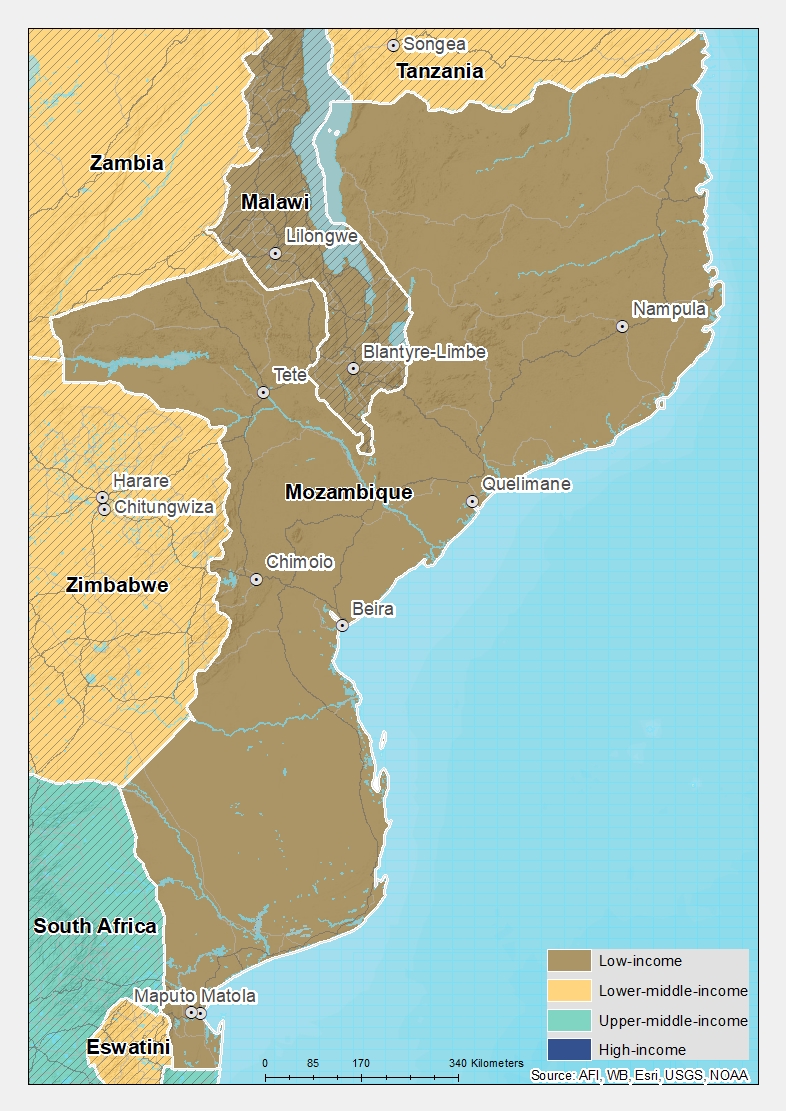

- Chart 1: Mozambique, political map

- Chart 2: Visual representation of International Futures (IFs) modelling platform

- Chart 3: Mozambique liquefied natural gas map

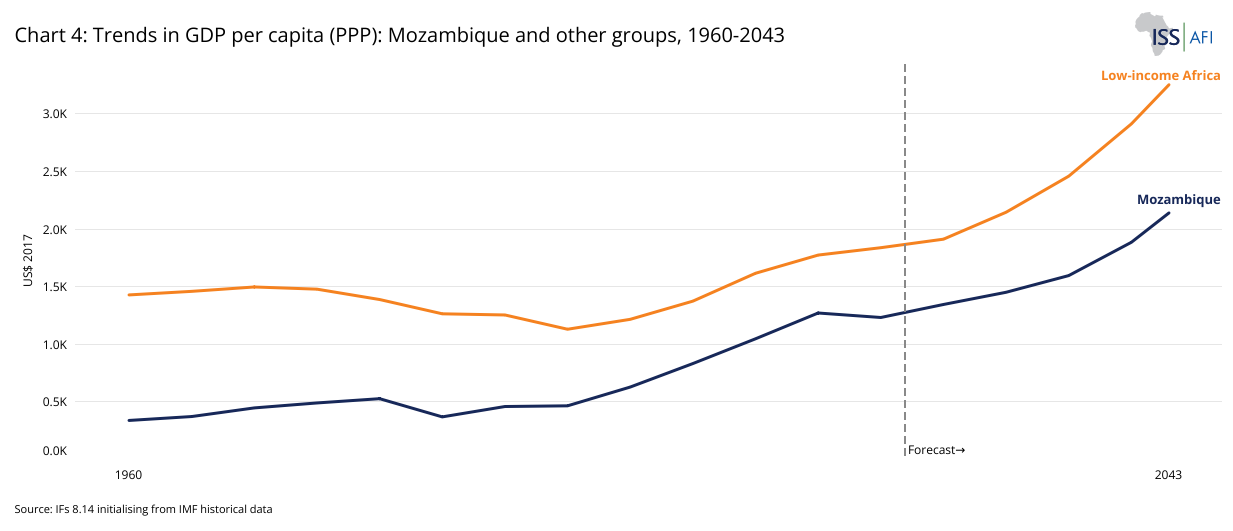

- Chart 4: Trends in GDP per capita (PPP): Mozambique and other groups, 1960-2043

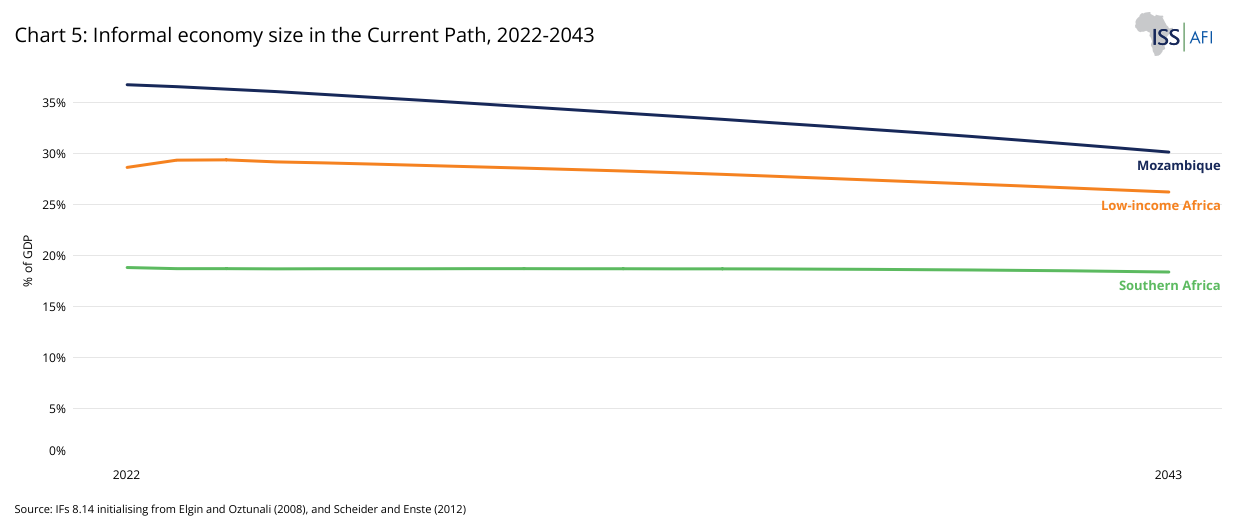

- Chart 5: Informal Economy size in the Current Path, 2022–2043

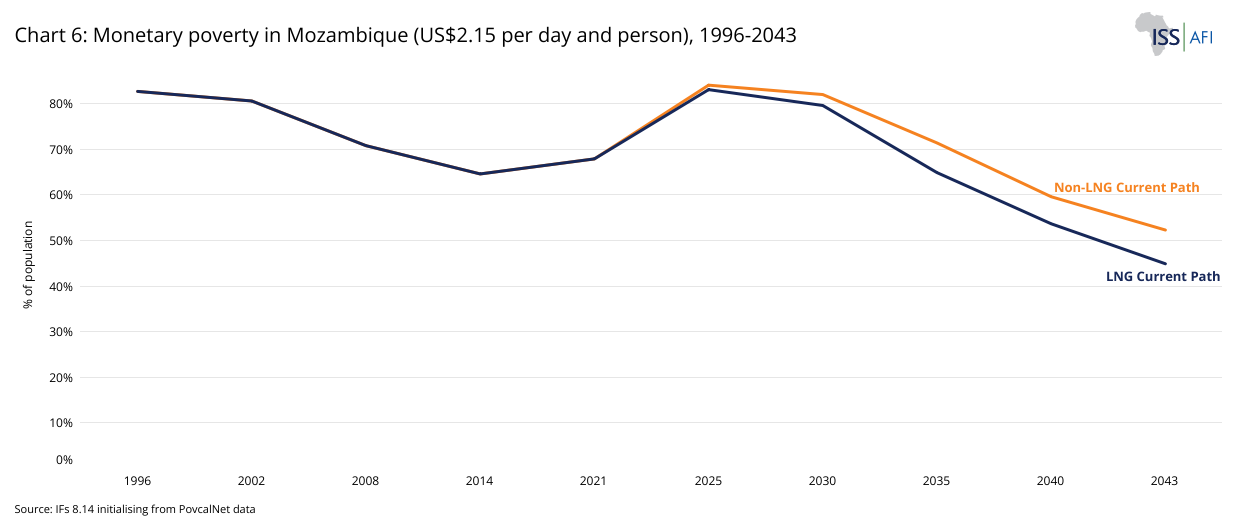

- Chart 6: Monetary poverty in Mozambique (<US$2.15 per day and person), 1996–2043

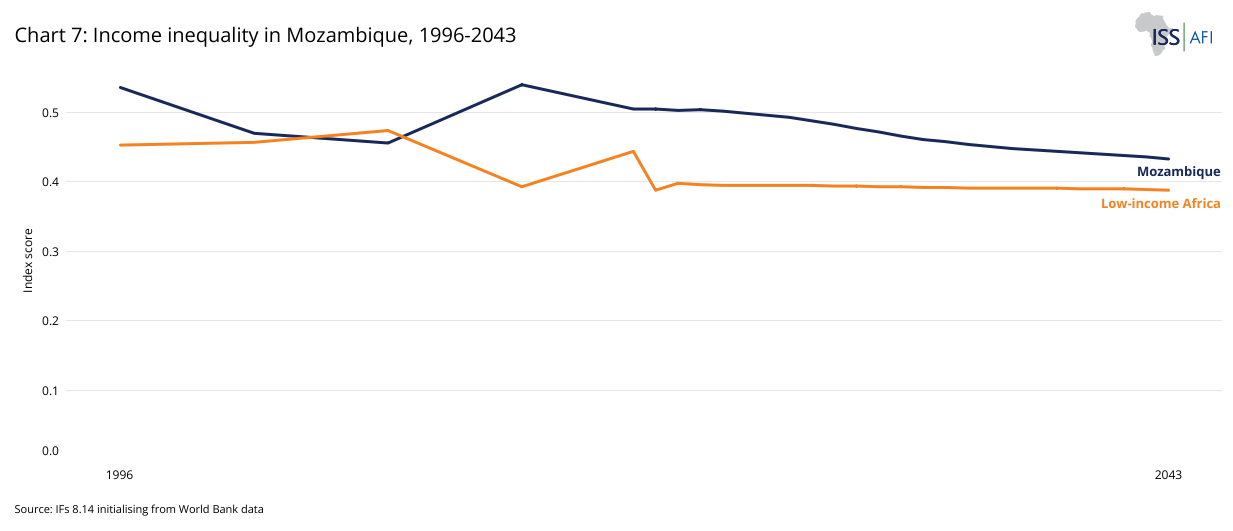

- Chart 7: Income inequality in Mozambique, 1996-2043

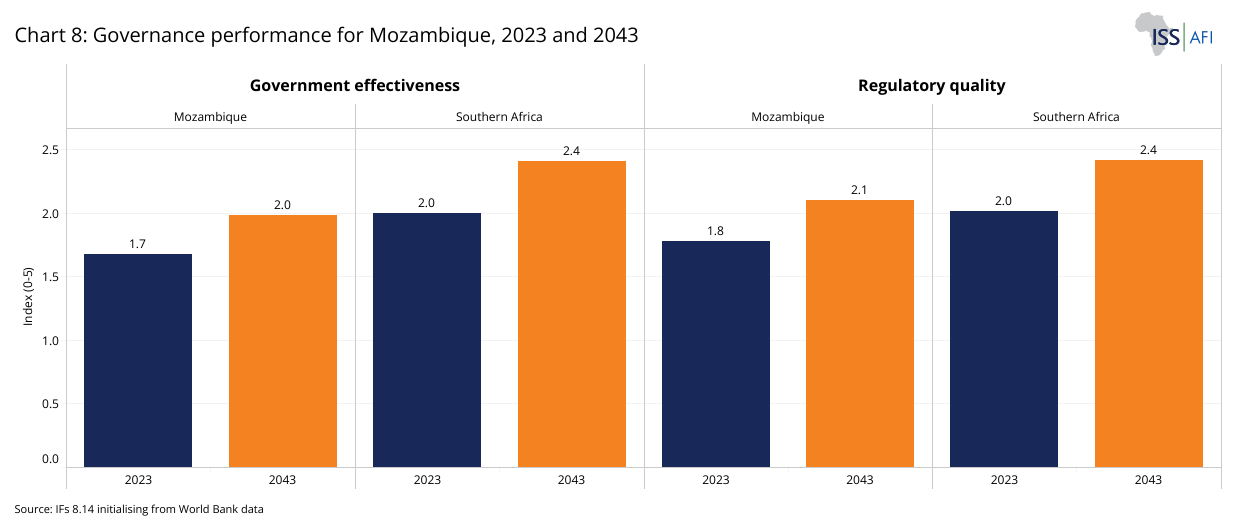

- Chart 8: Governance performance for Mozambique, 2023 and 2043

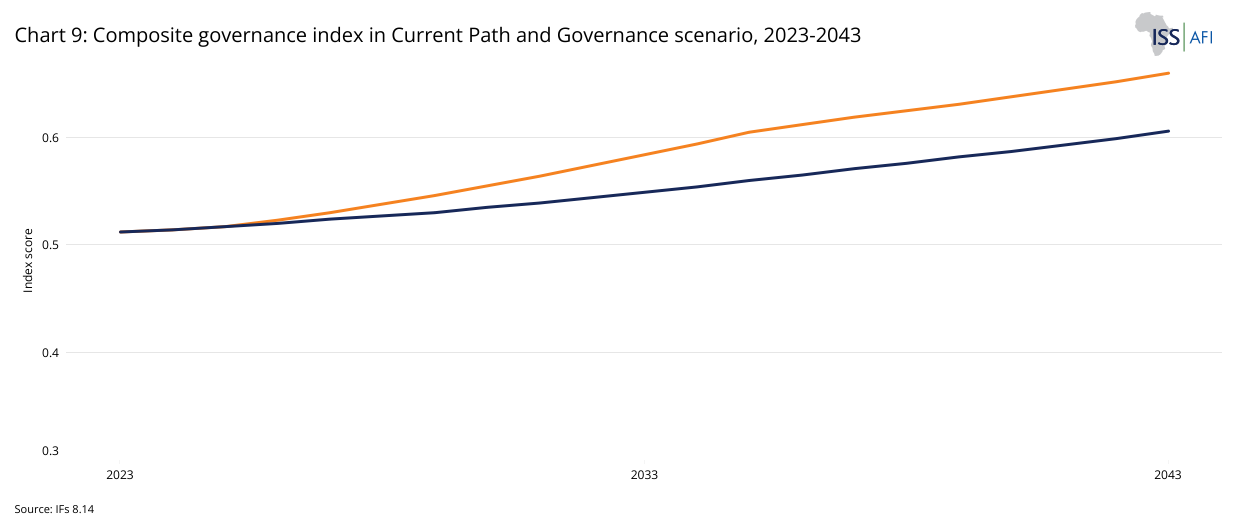

- Chart 9: Composite governance index in Current Path and Governance scenario, 2023-2043

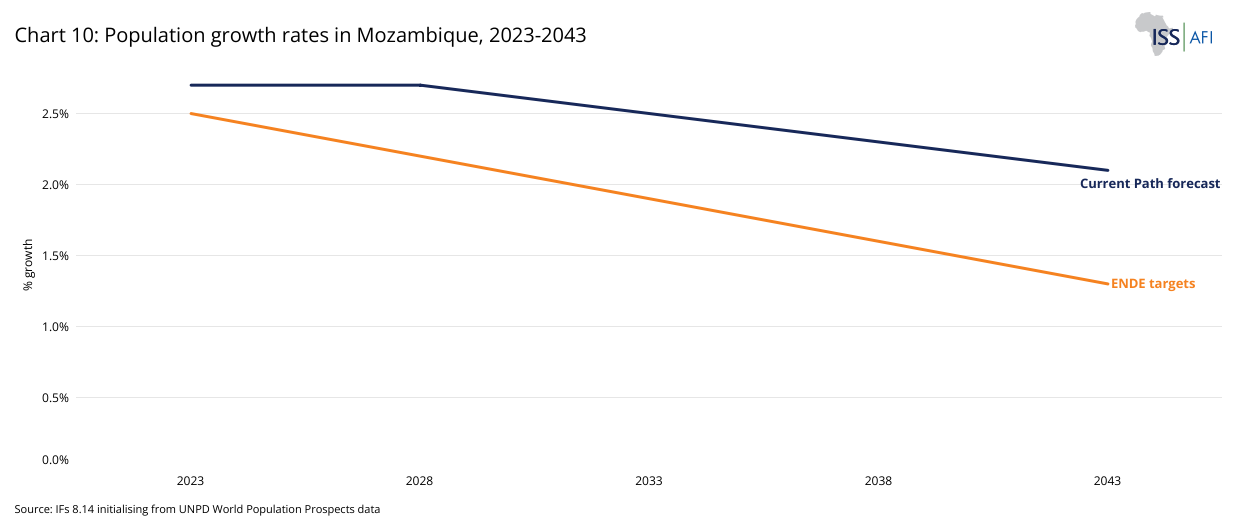

- Chart 10: Population growth rates in Mozambique, 2023-2043

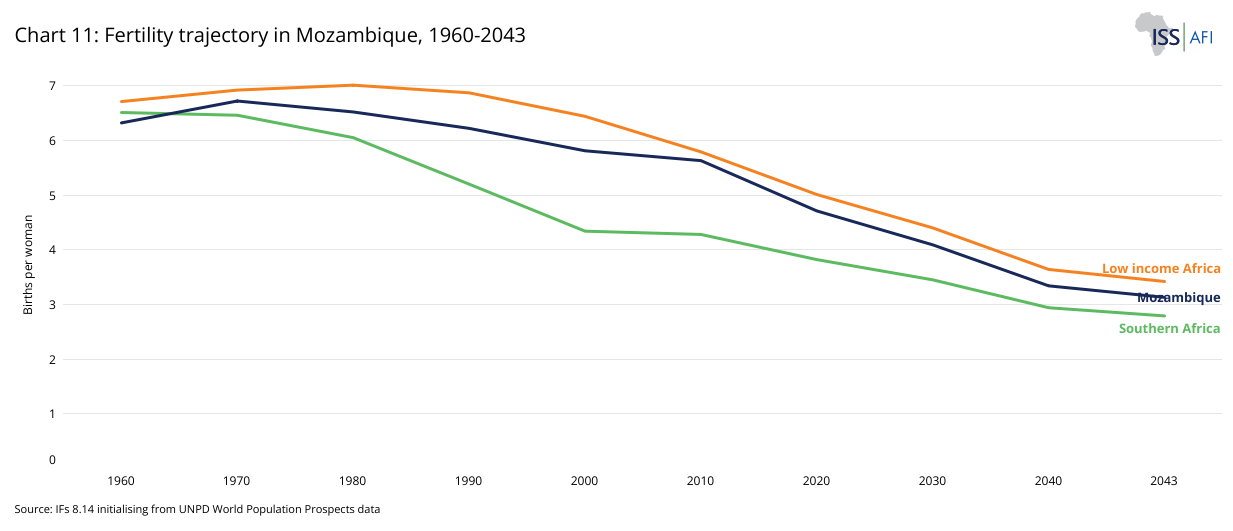

- Chart 11: Fertility trajectory in Mozambique, 1960-2043

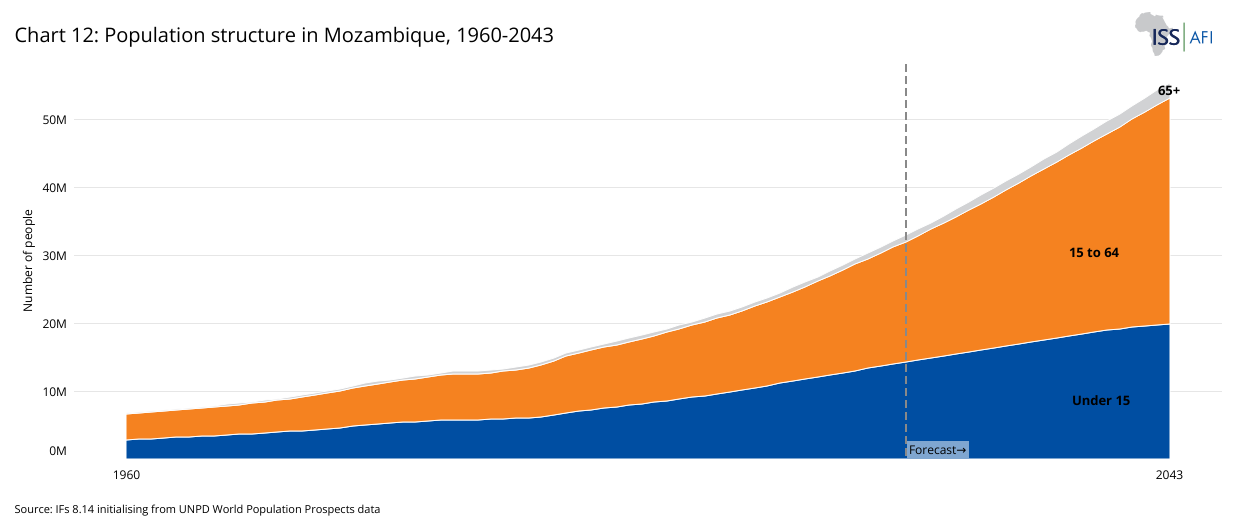

- Chart 12: Population structure in Mozambique, 1960-2043

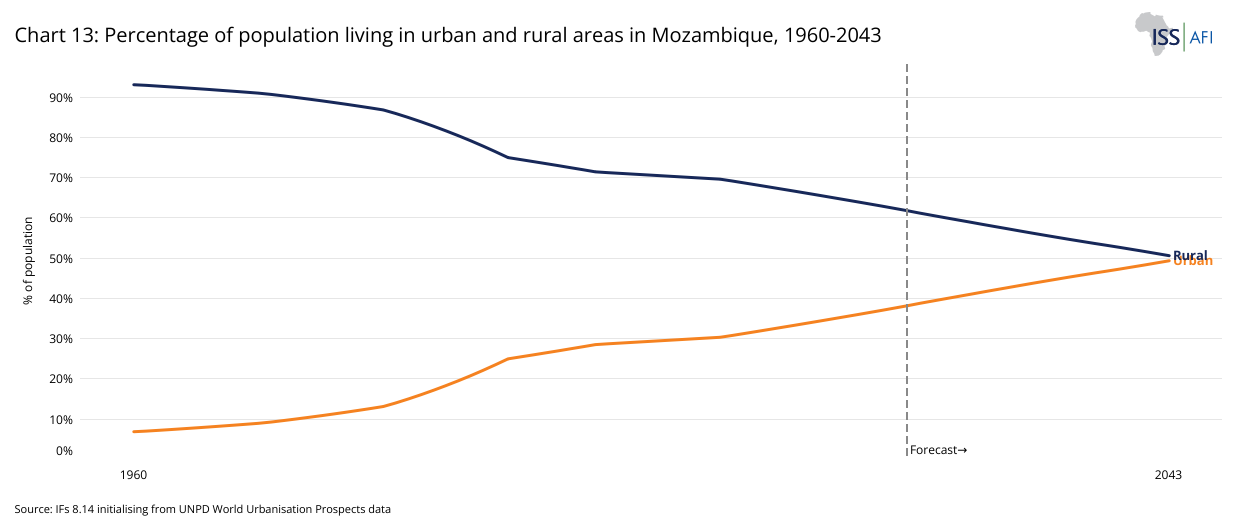

- Chart 13: Percentage of population living in urban and rural areas in Mozambique, 1960-2043

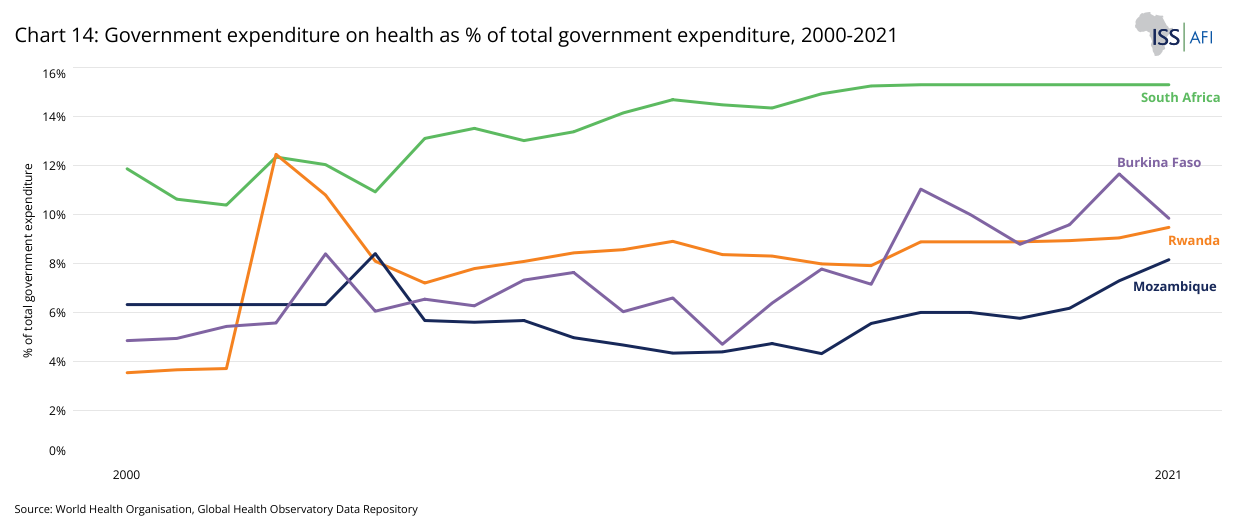

- Chart 14: Government expenditure on health as % of total government expenditure, 2000-2021

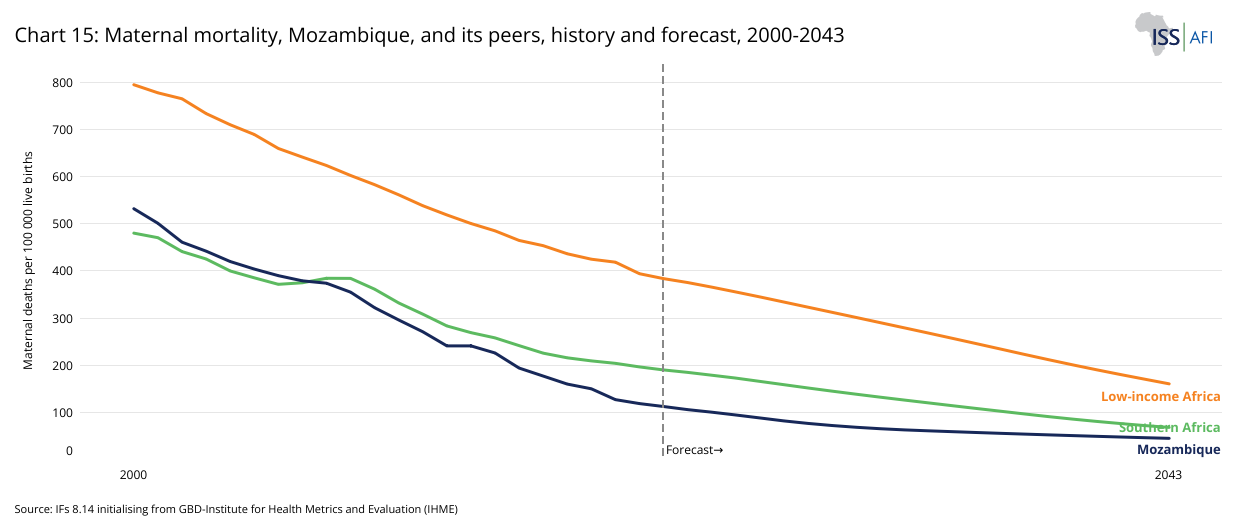

- Chart 15: Maternal mortality, Mozambique, and its peers, history and forecast, 2000-2043

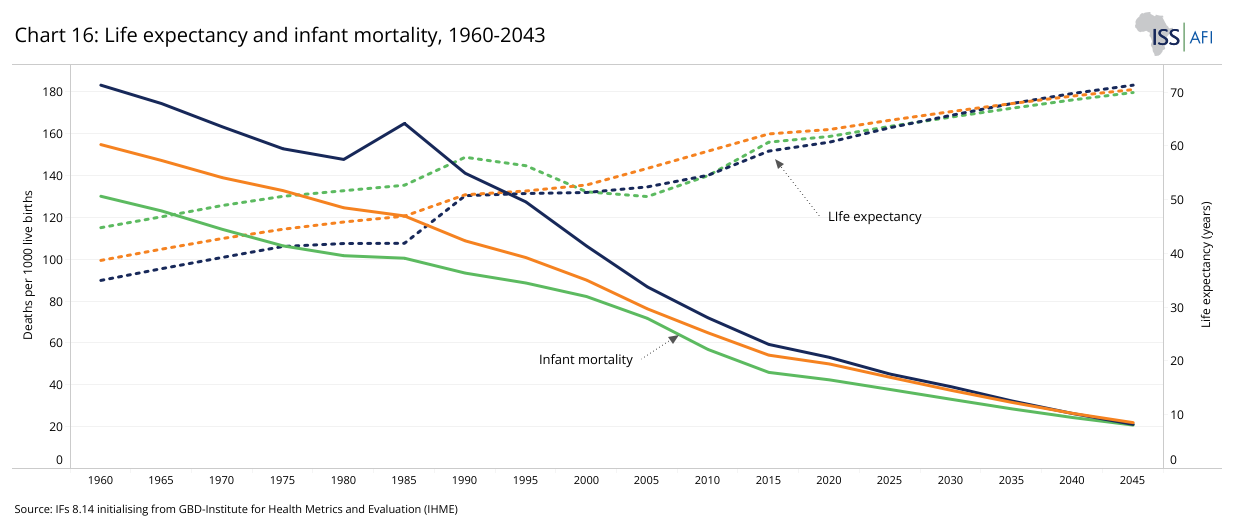

- Chart 16: Life expectancy and infant mortality, 1960-2043

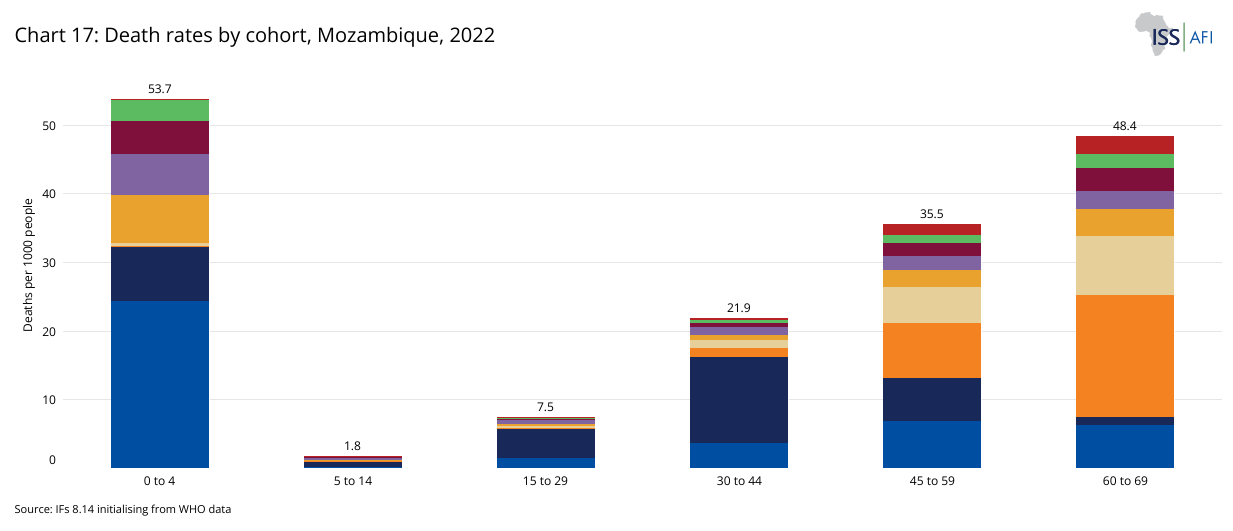

- Chart 17: Death rates by cohort, Mozambique, 2022

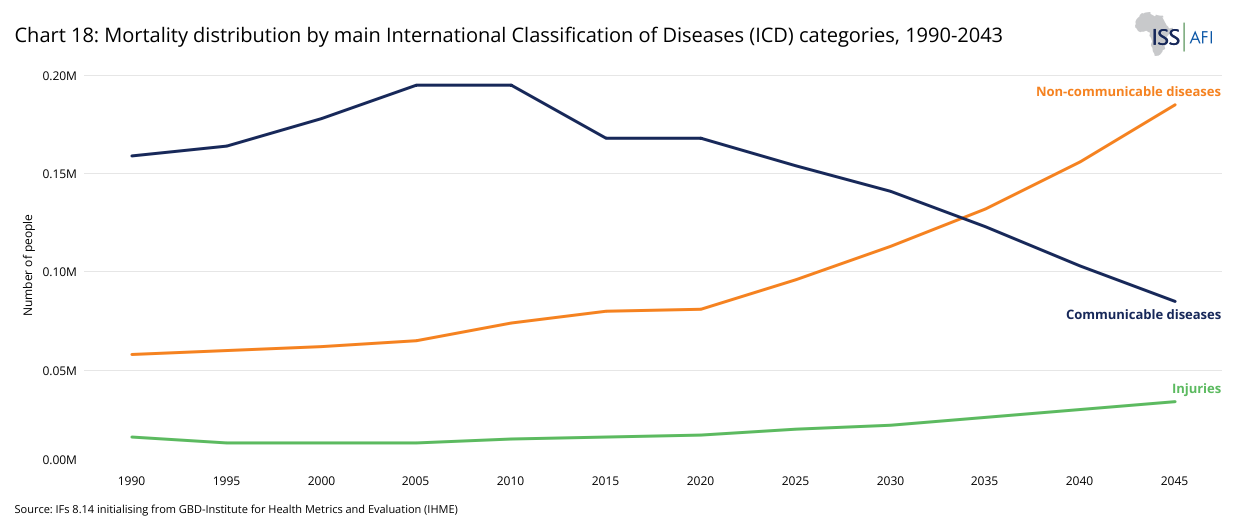

- Chart 18: Mortality distribution by main International Classification of Diseases (ICD) categories, 1990-2043

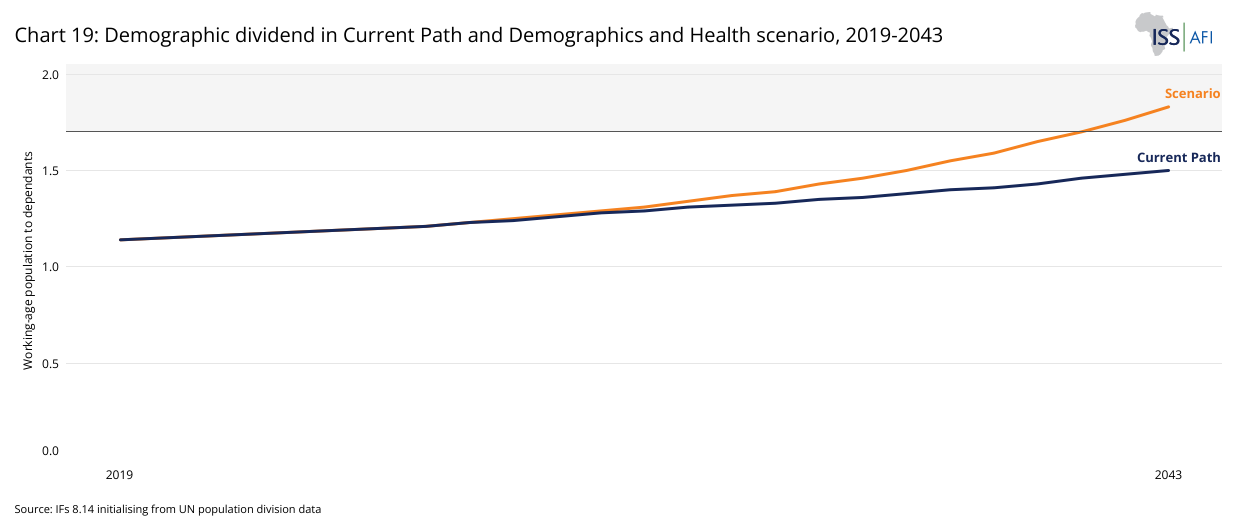

- Chart 19: Demographic dividend in Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 2019–2043

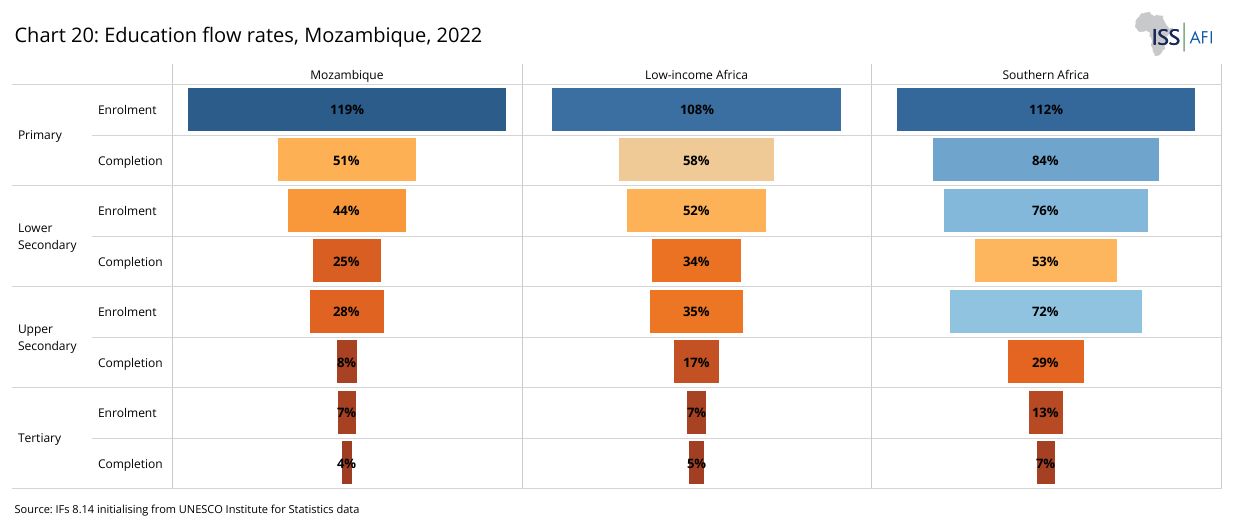

- Chart 20: Education flow rates, Mozambique, 2022

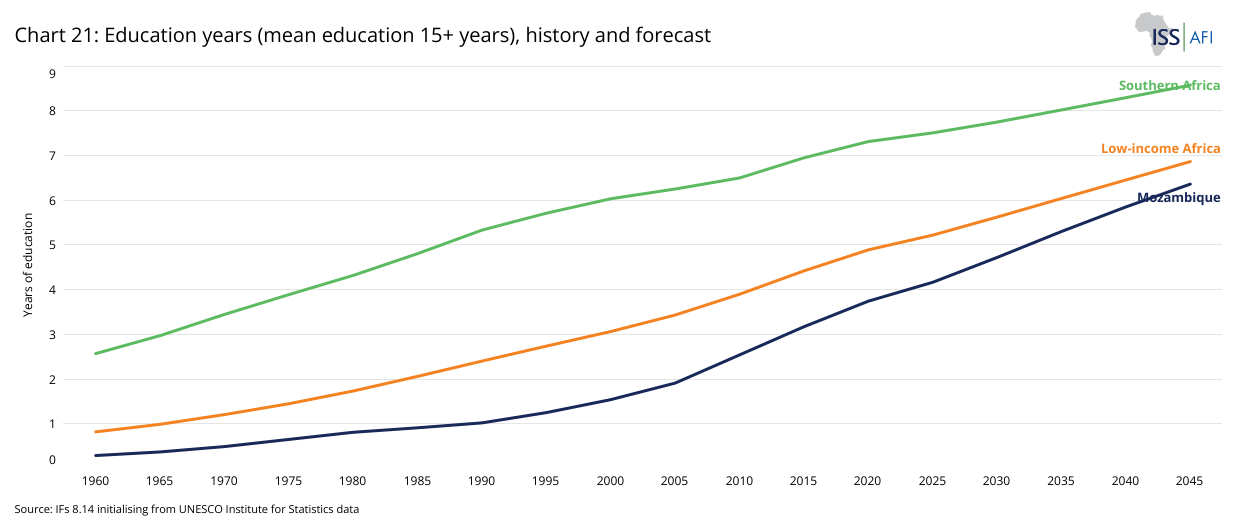

- Chart 21: Education years (mean education 15+ years), history and forecast

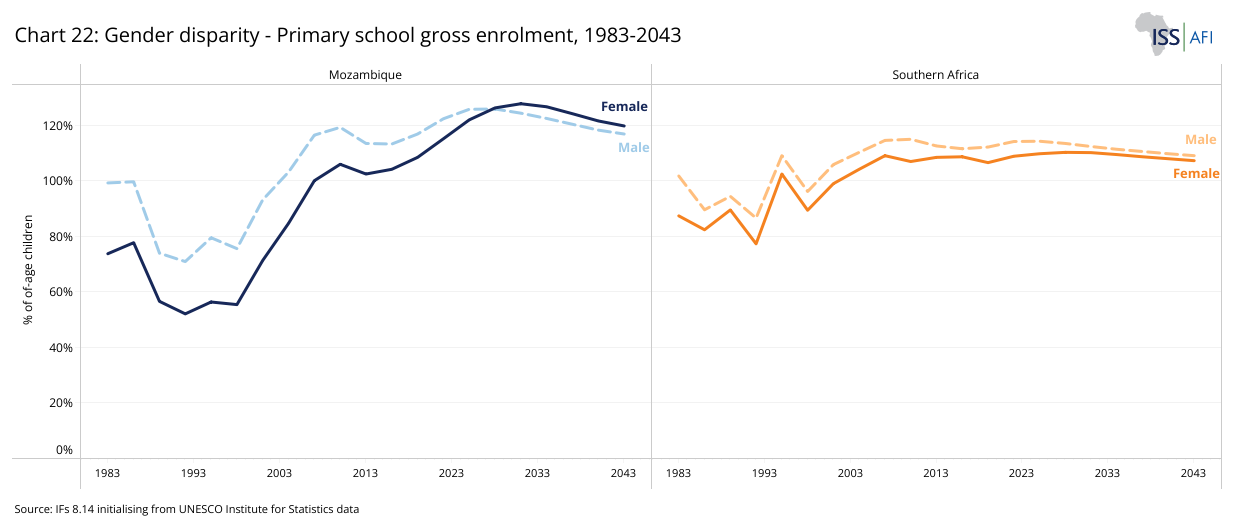

- Chart 22: Gender disparity - Primary school gross enrolment, 1983-2043

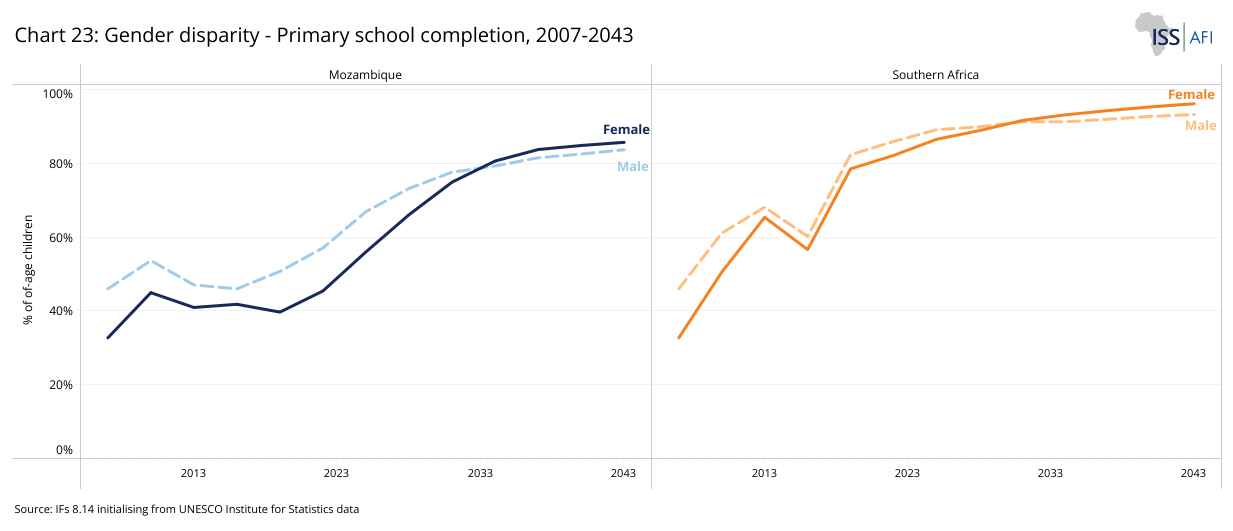

- Chart 23: Gender disparity - Primary school completion, 2007-2043

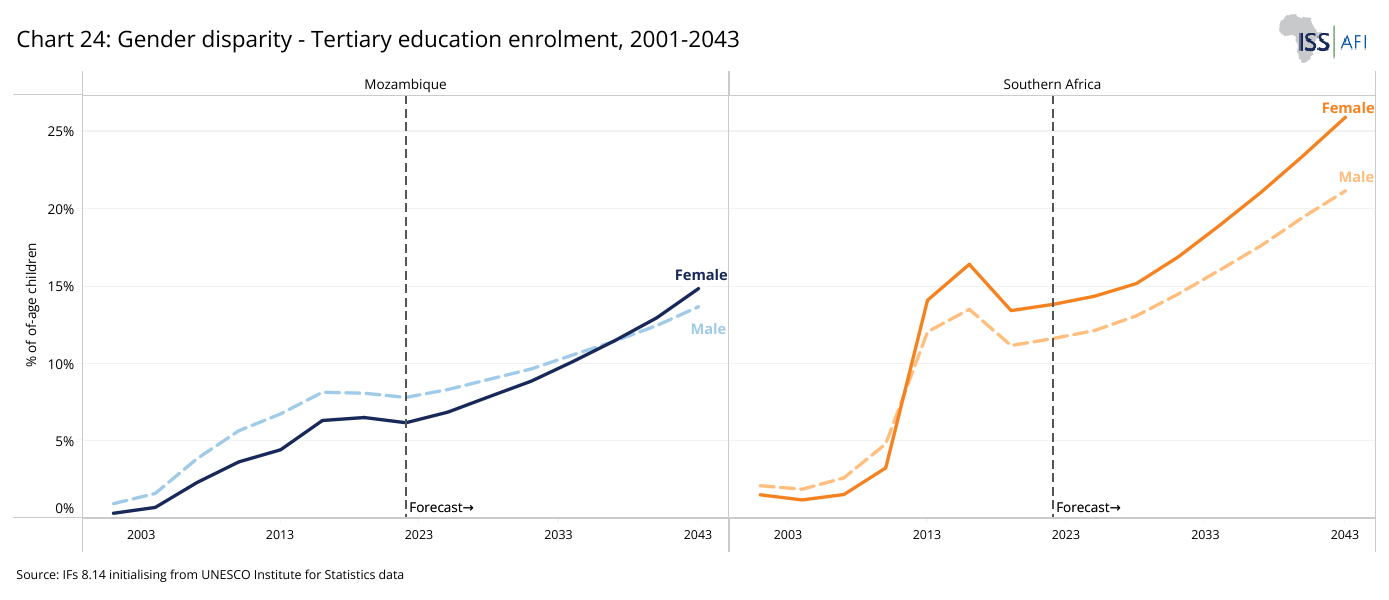

- Chart 24: Gender disparity - Tertiary education enrolment, 2001-2043

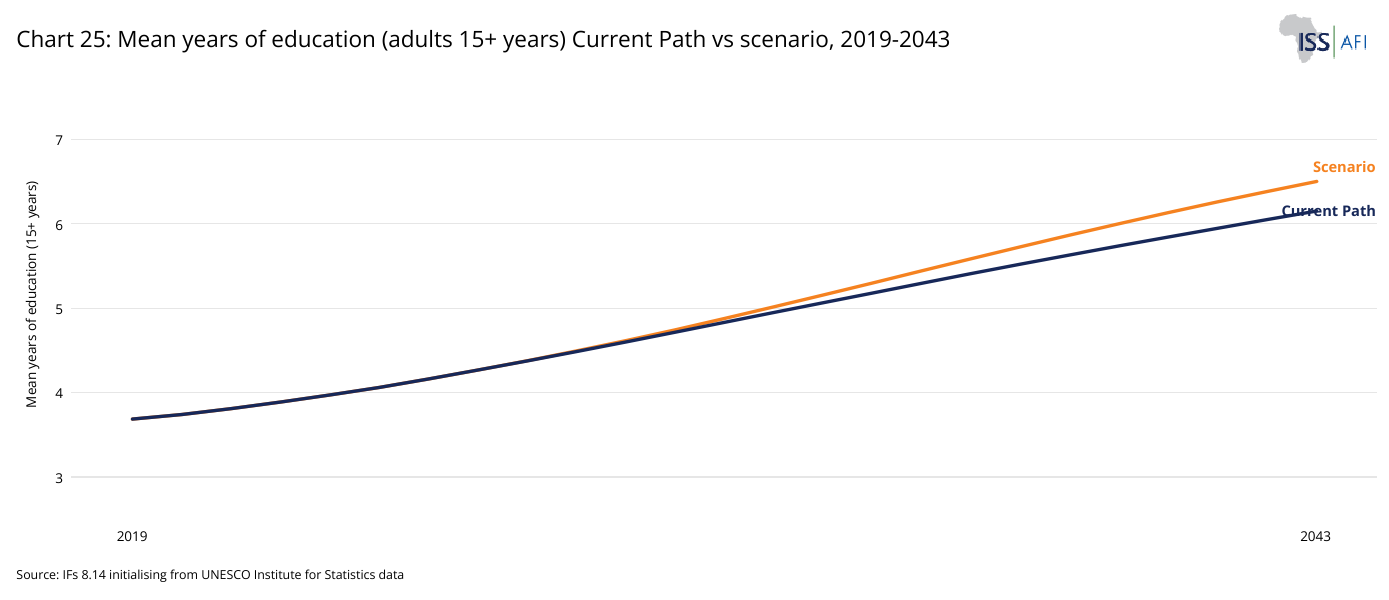

- Chart 25: Mean years of education (adults 15+ years) Current Path vs scenario, 2019-2043

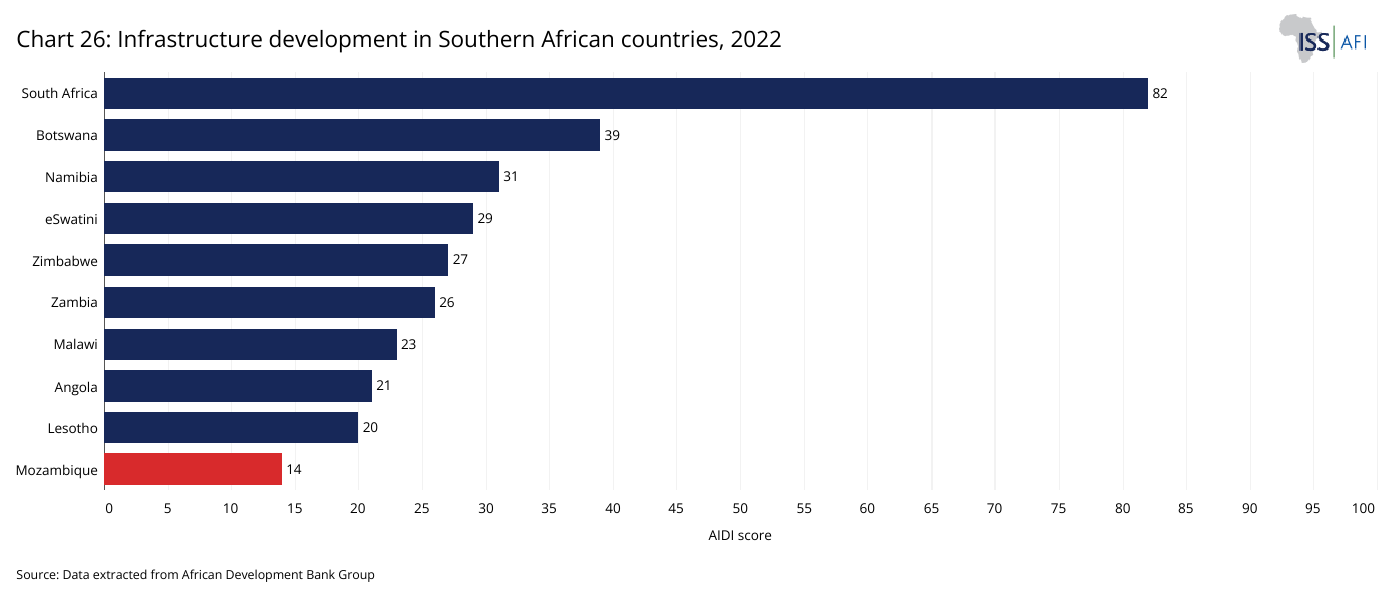

- Chart 26: Infrastructure development in Southern African countries, 2022

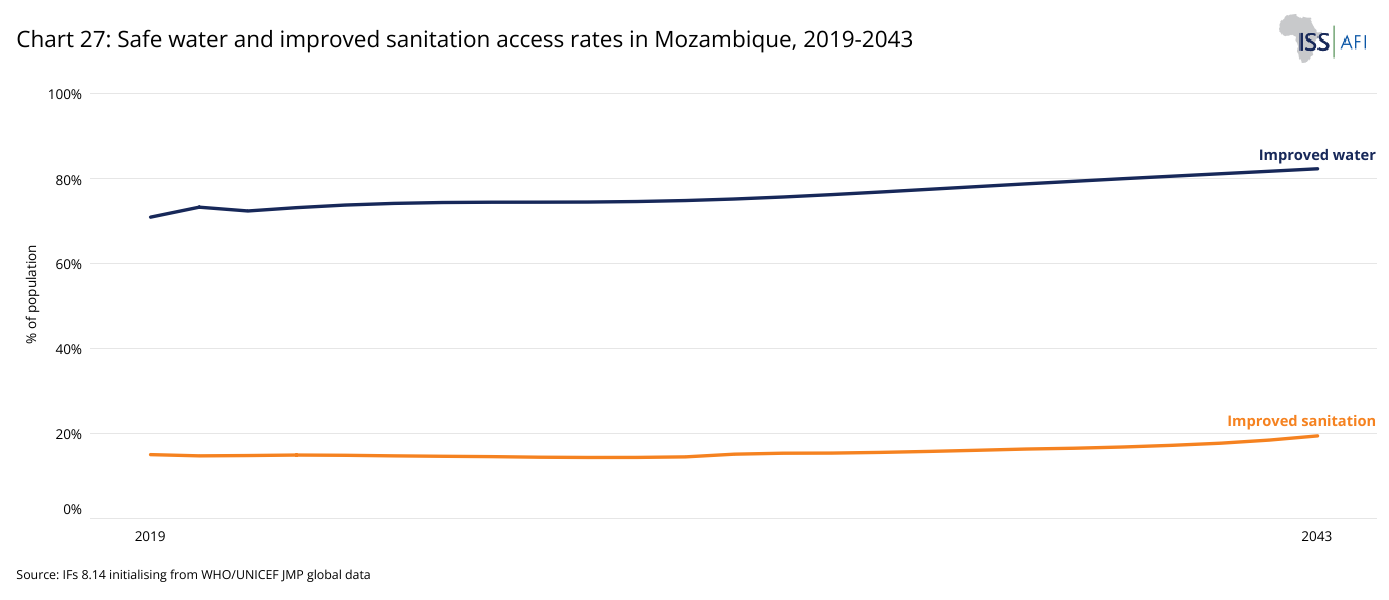

- Chart 27: Safe water and improved sanitation access rates in Mozambique, 2019–2043

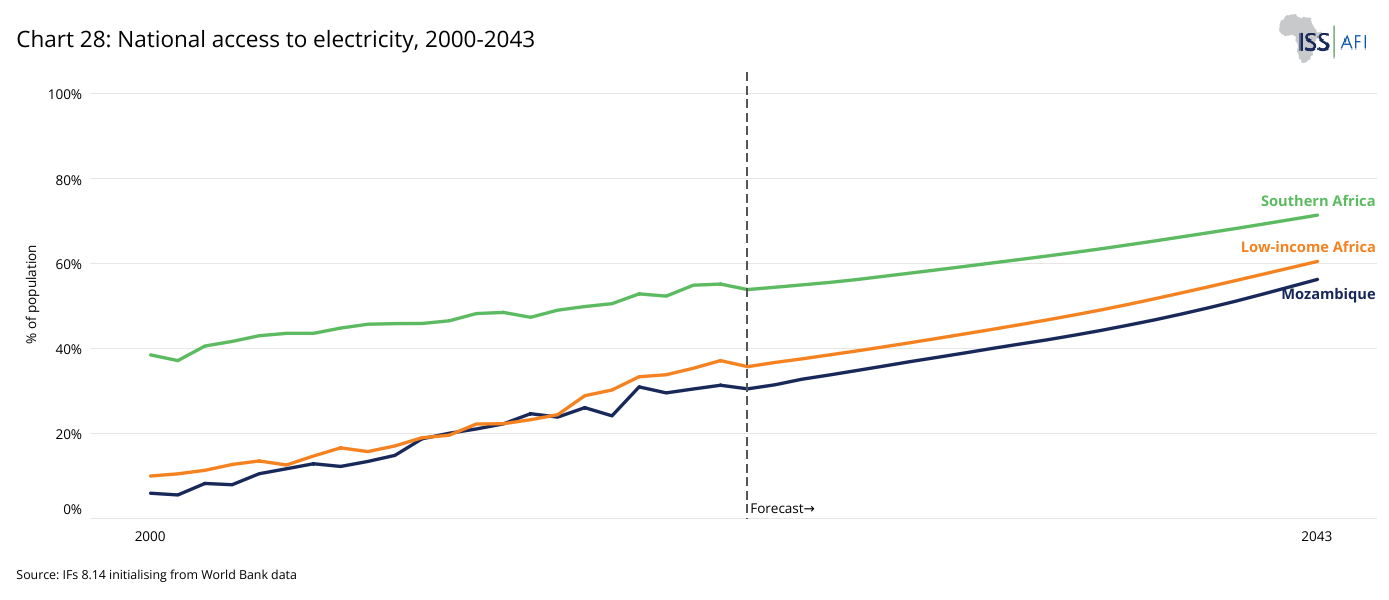

- Chart 28: National access to electricity, 2000-2043

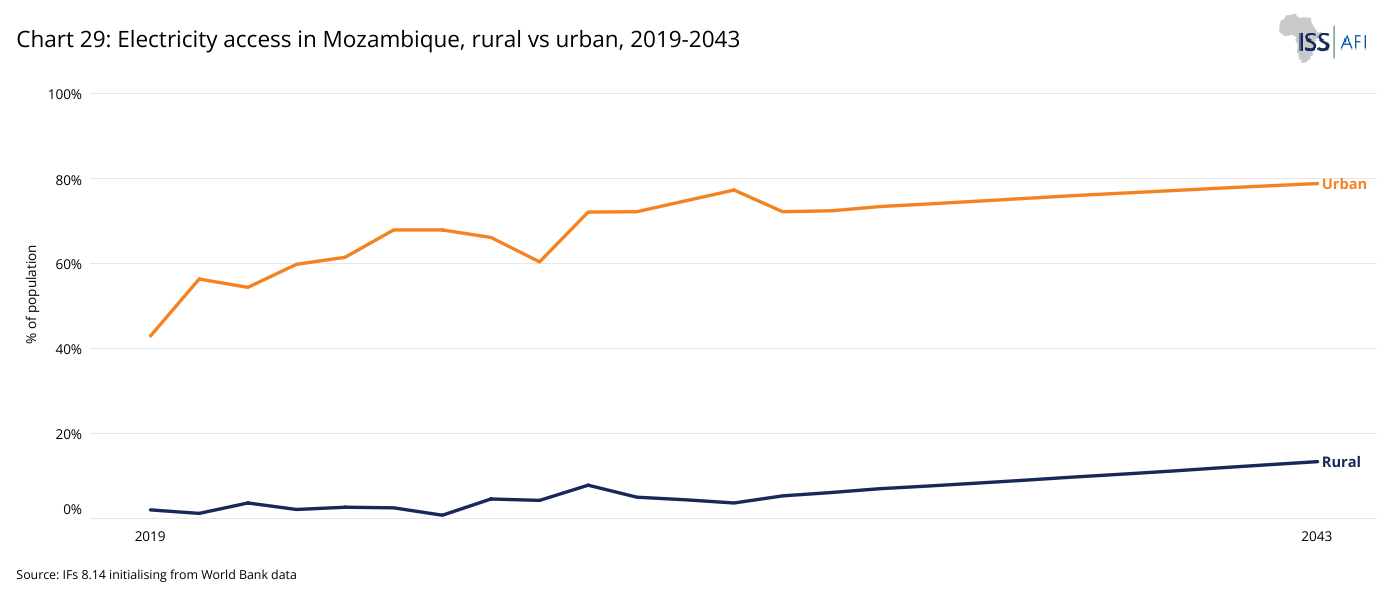

- Chart 29: Electricity access in Mozambique, rural vs urban, 2019-2043

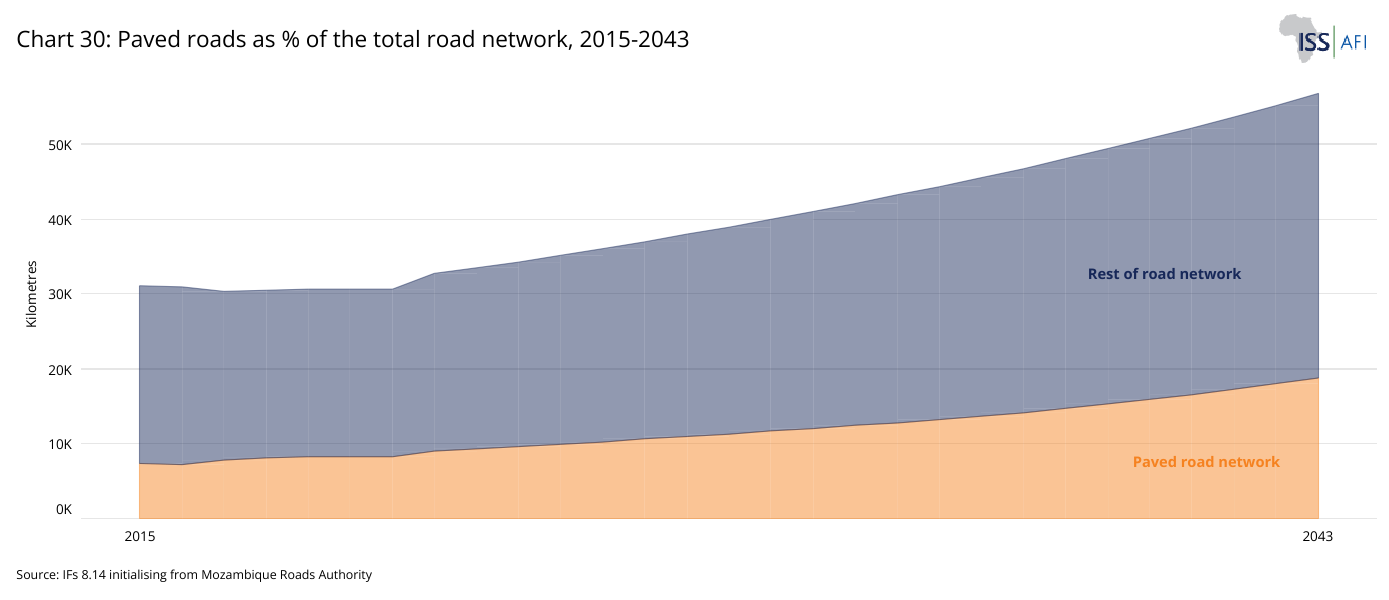

- Chart 30: Paved roads as % of the total road network, 2015-2043

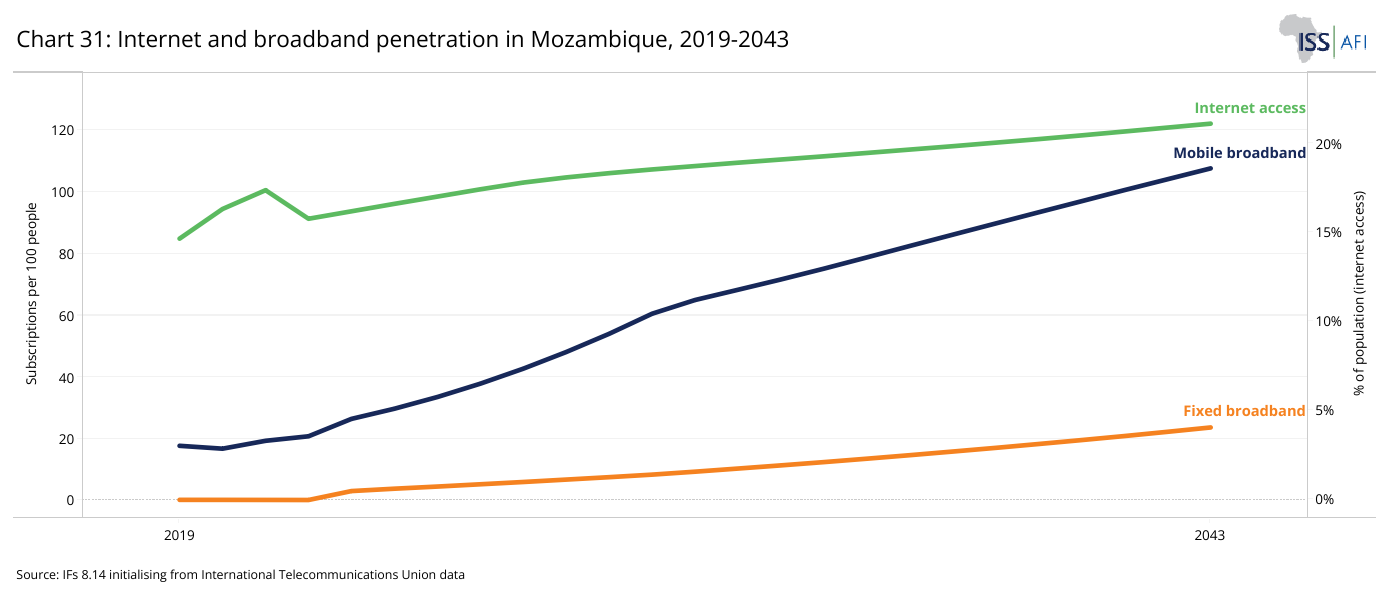

- Chart 31: Internet and broadband penetration in Mozambique, 2019-2043

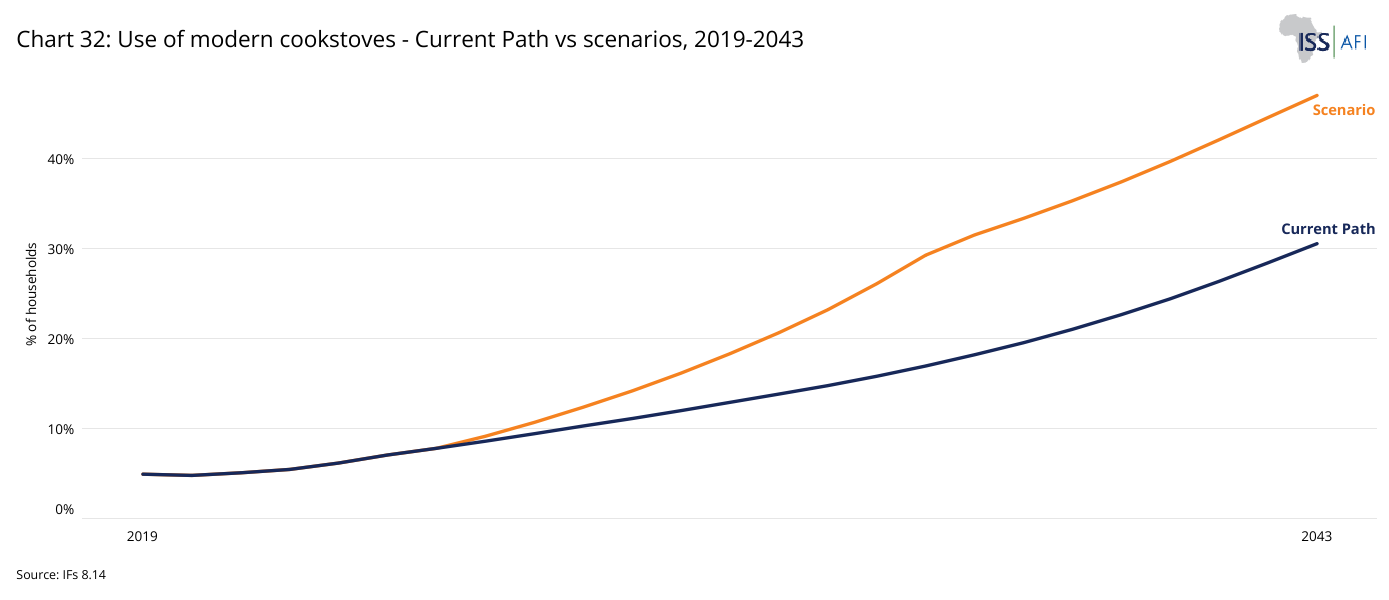

- Chart 32: Use of modern cookstoves - Current Path vs scenario, 2019-2043

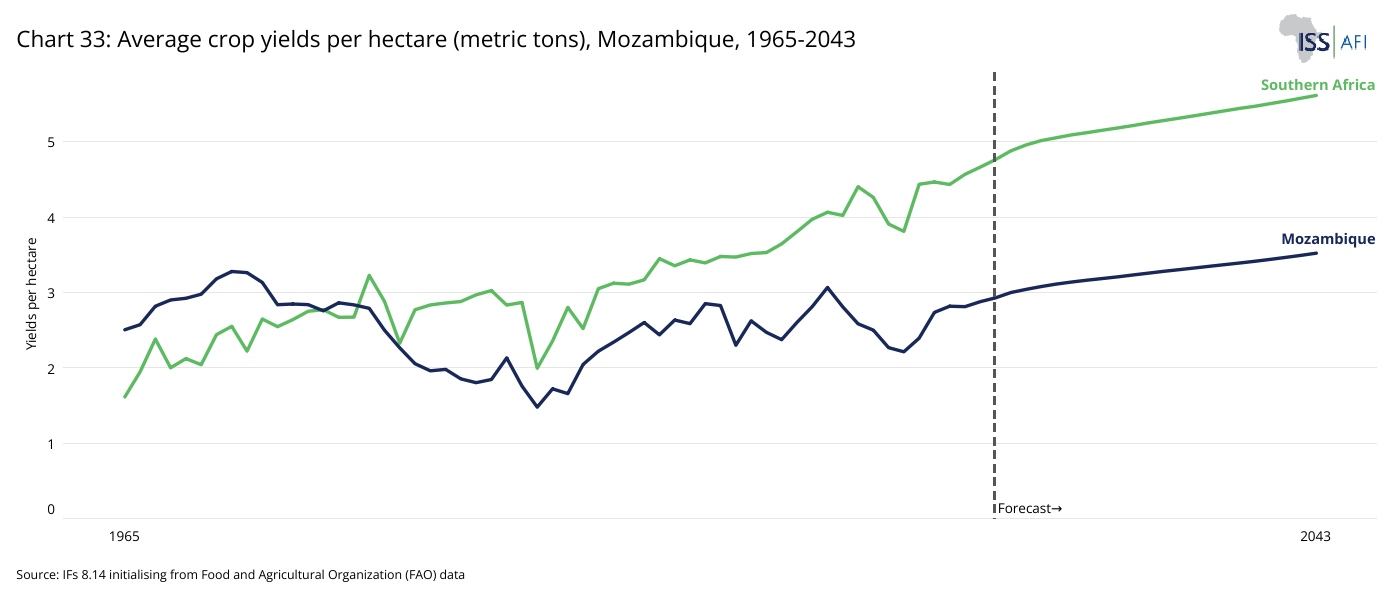

- Chart 33: Average crop yields per hectare (metric tons), Mozambique, 1965-2043

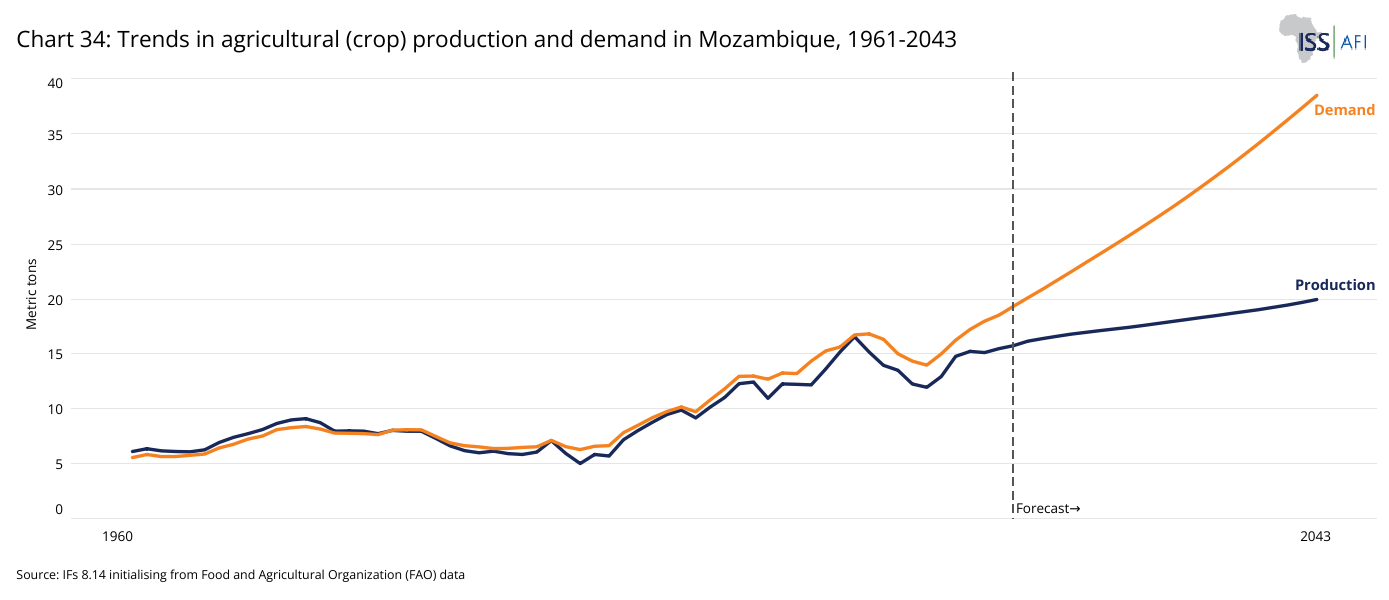

- Chart 34: Trends in agricultural (crop) production and demand in Mozambique, 1961-2043

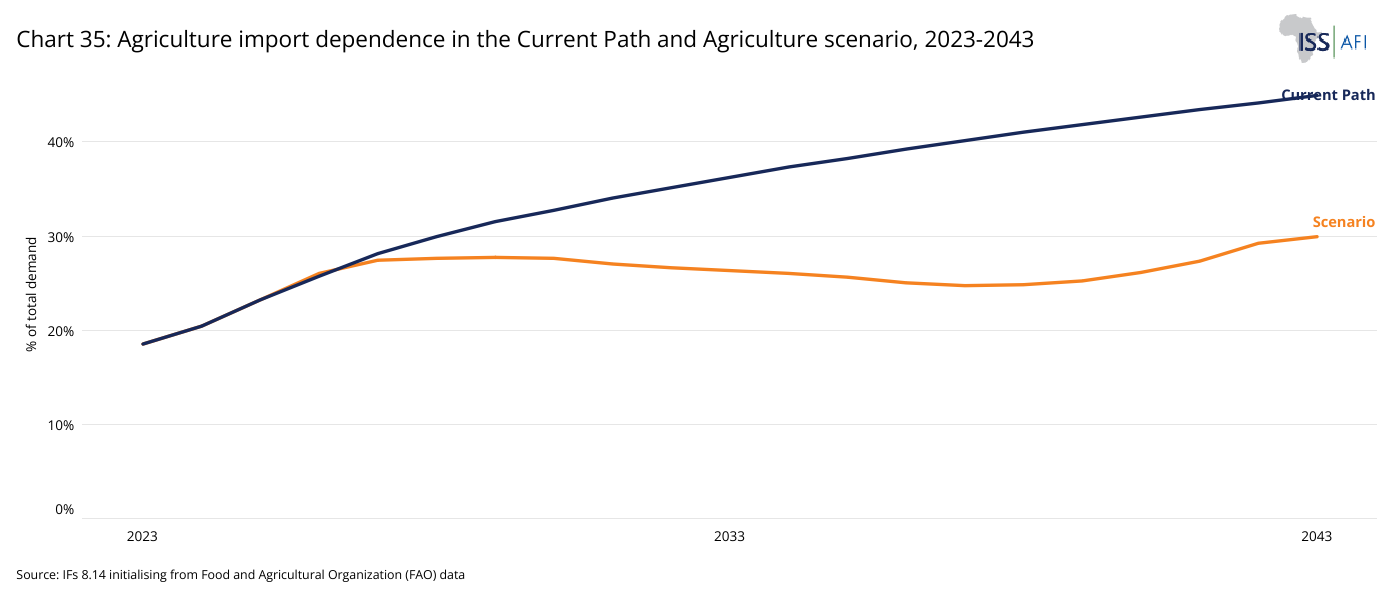

- Chart 35: Agriculture import dependence in the Current Path and Agriculture scenario, 2023–2043

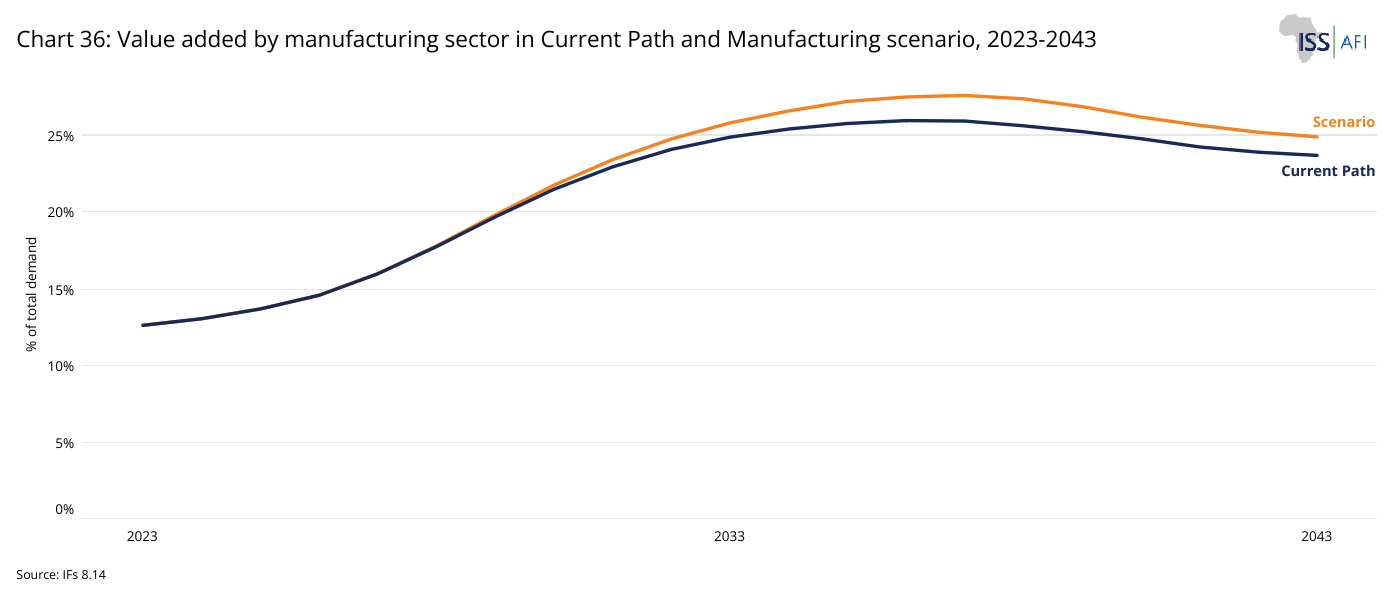

- Chart 36: Value added by manufacturing sector in Current Path and Manufacturing scenario, 2023-2043

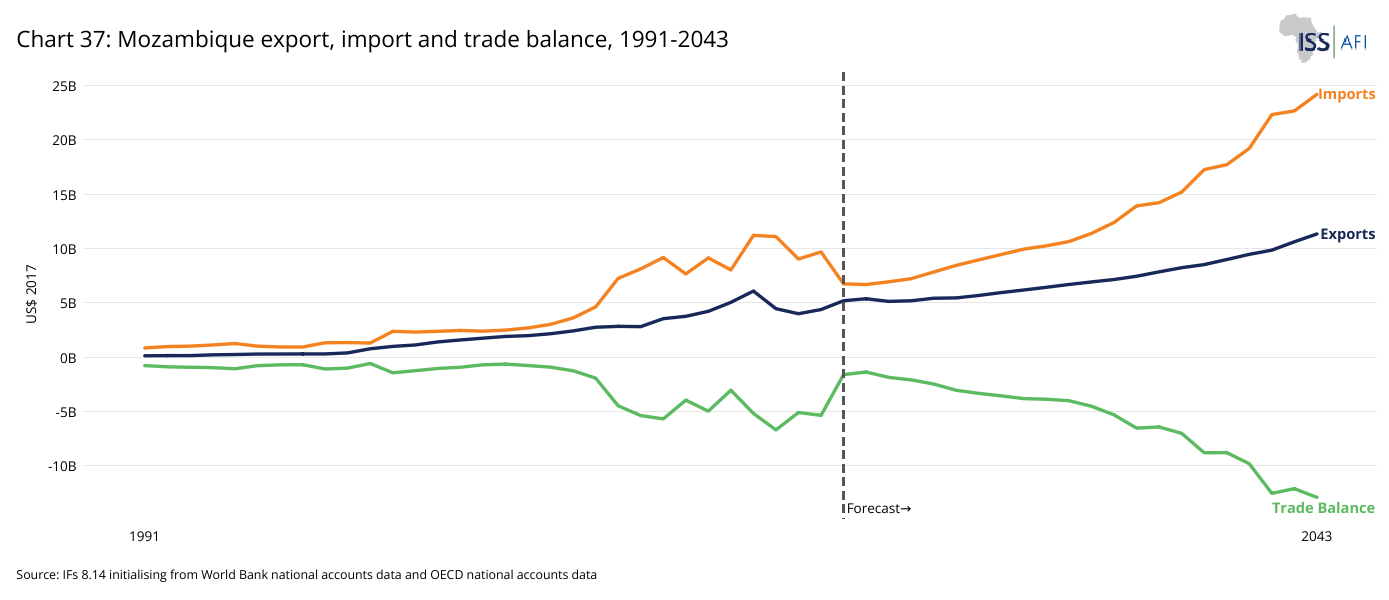

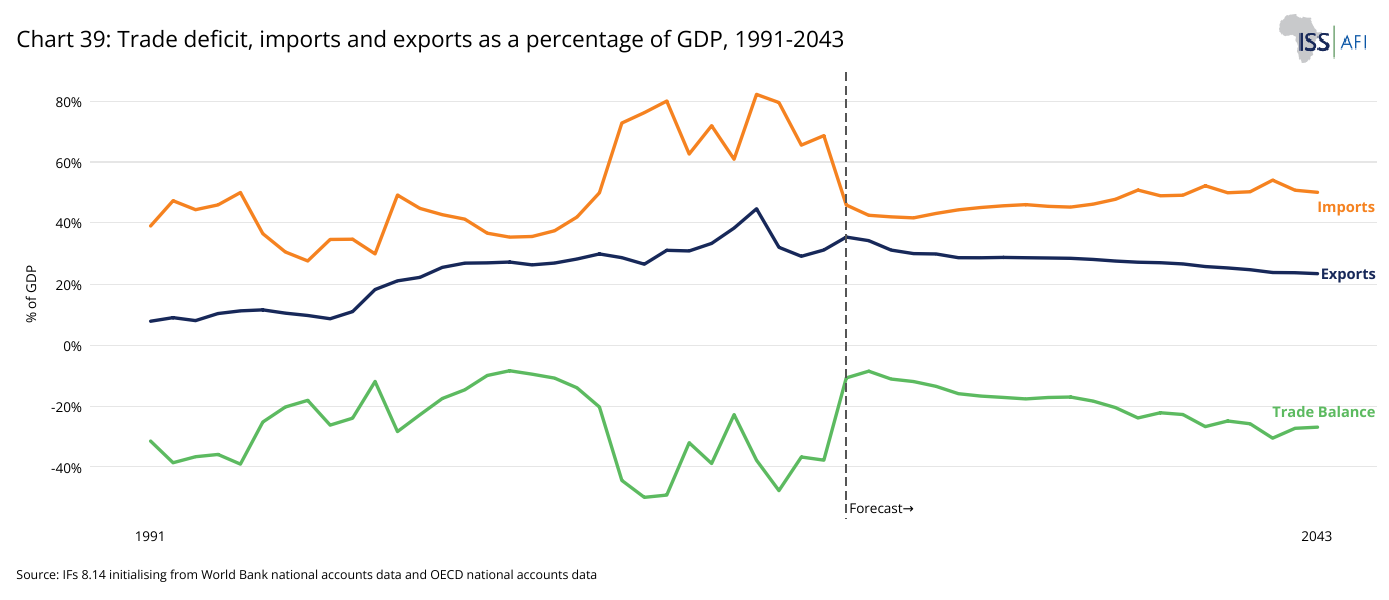

- Chart 37: Mozambique export, imports and trade balance, 1991-2043

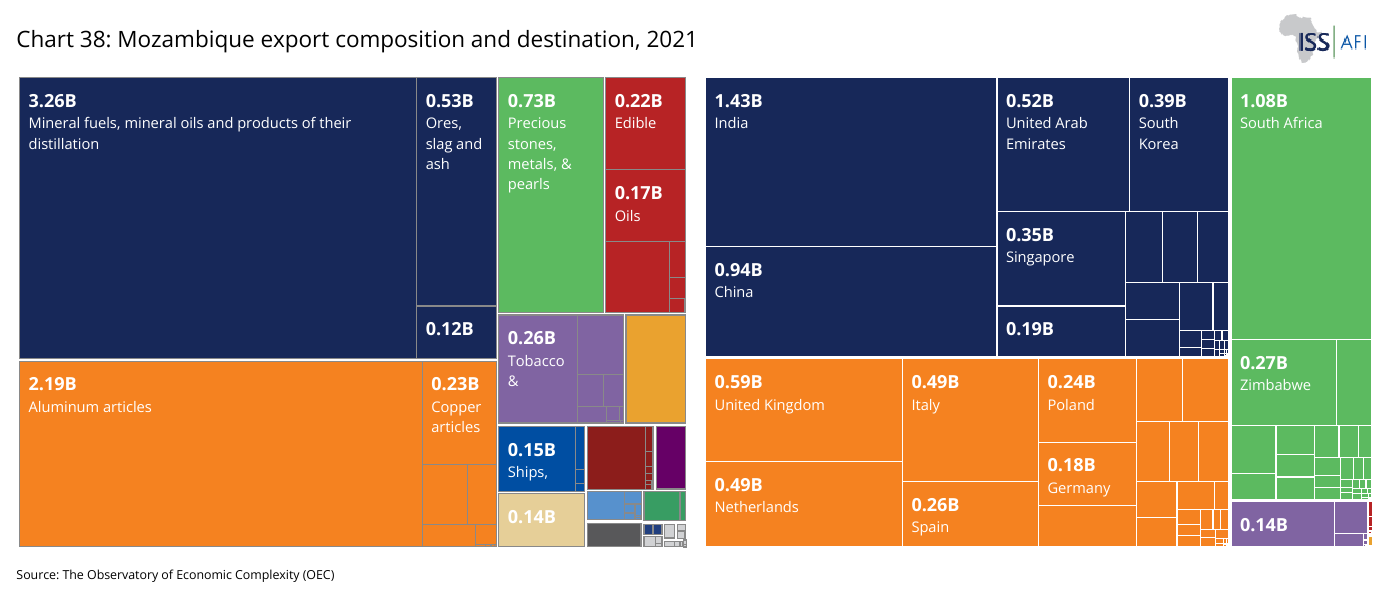

- Chart 38: Mozambique export composition and destination, 2021

- Chart 39: Trade deficit, imports and exports as a percentage of GDP, 1991-2043

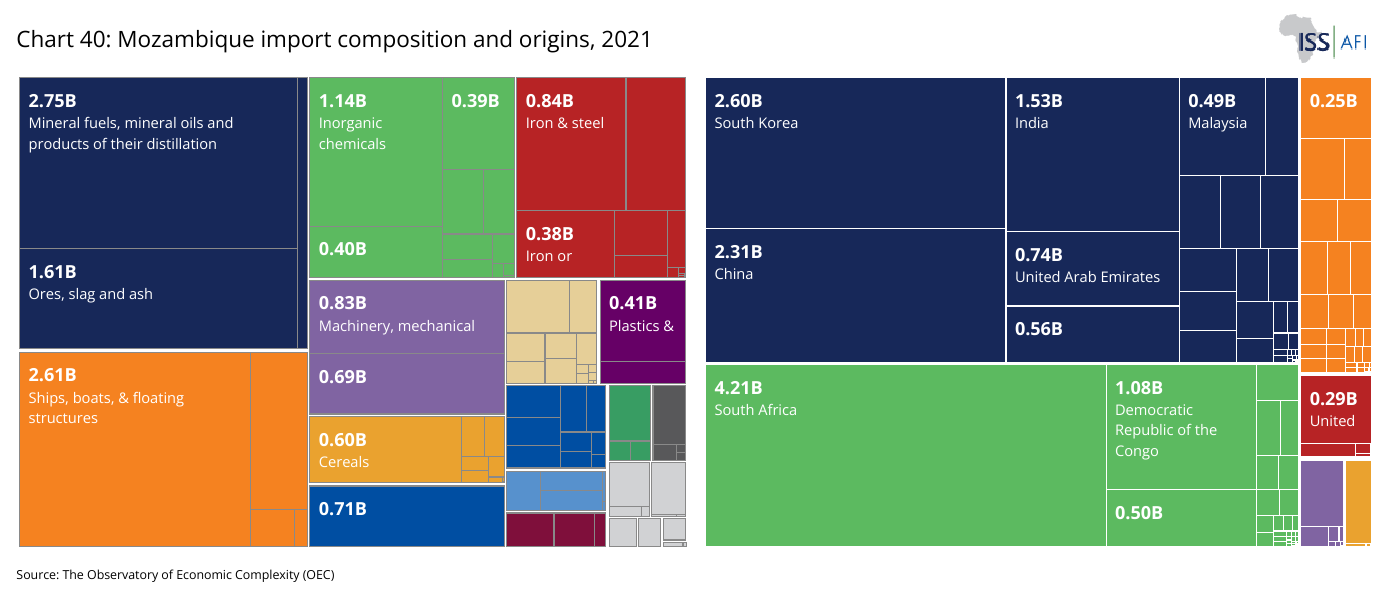

- Chart 40: Mozambique import composition and origins, 2021

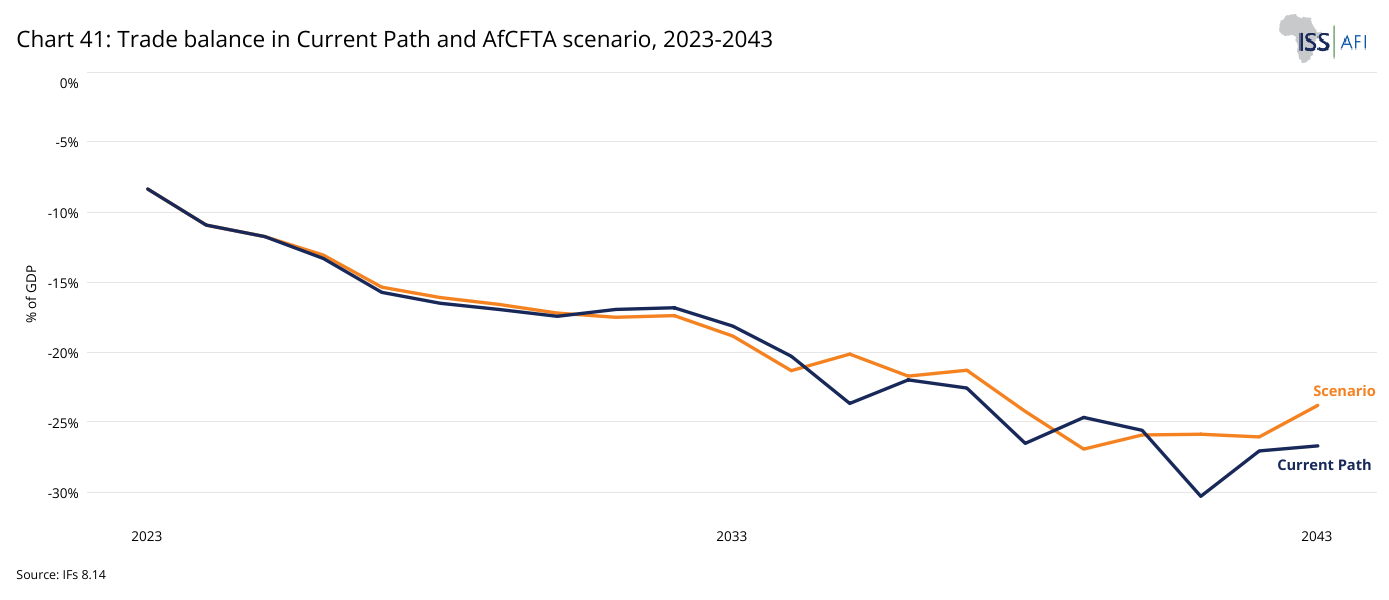

- Chart 41: Trade balance in Current Path and AfCFTA scenario, 2023-2043

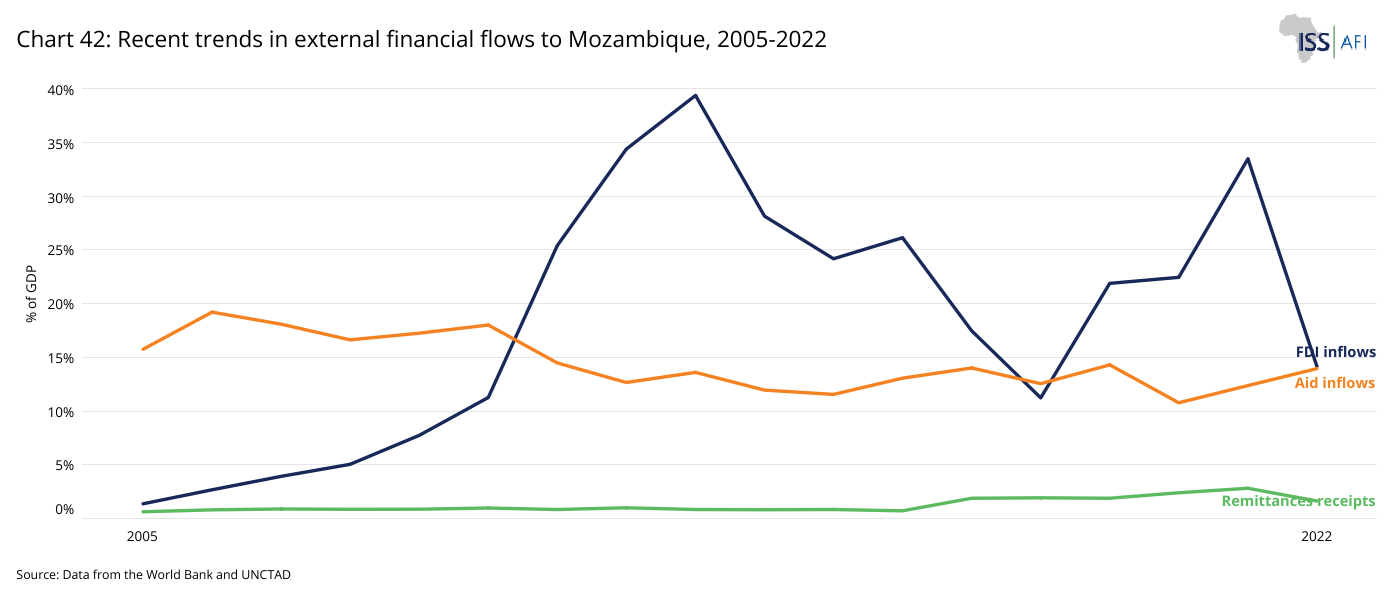

- Chart 42: Recent trends in external financial flows to Mozambique, 2005–2022

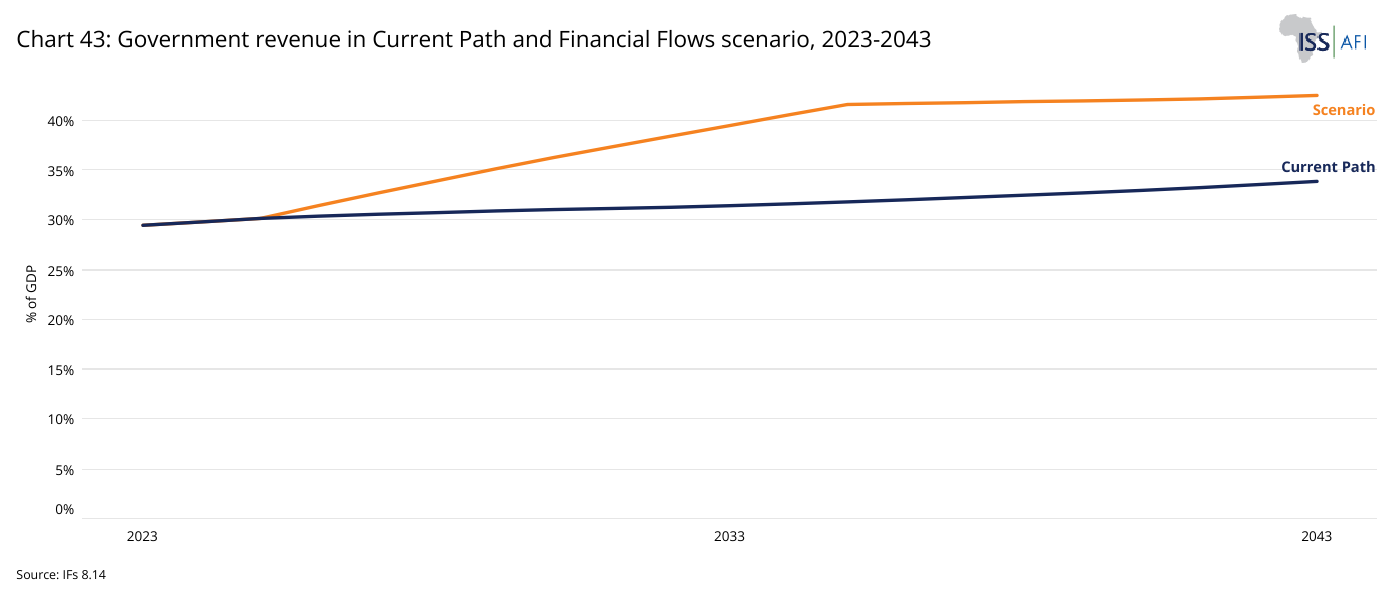

- Chart 43: Government revenue in Current Path and Financial Flows scenario, 2023-2043

- Chart 44: Increase in the size of the Mozambican economy (GDP) in each scenario relative to the Current Path, 2033 and 2043

- Chart 45: Increase in GDP per capita (PPP) in each scenario relative to the Current Path, 2033 and 2043

- Chart 46: Decrease in poverty headcount (<US$2.15 per day) in each scenario relative to the Current Path, 2033 and 2043

- Chart 47: GDP in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023-2043

- Chart 48: GDP per capita (PPP) in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023-2043

- Chart 49: Extreme Poverty (<US$2.15 per day) in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023-2043

Located in Southern Africa, Mozambique is nestled between Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, South Africa and Eswatini. It is one of the 22 low-income countries in Africa and had an estimated population of about 33 million in 2023. The country has considerable mineral reserves, vast arable land and an extensive coastline along which flows the warm Mozambique current that feeds its rich aquatic life.

Mozambique achieved independence in 1975, but only after the end of a 15-year civil war in 1992 did it begin to experience socio-economic progress. Between 1993 and 2015, Mozambique was one of Africa’s fastest-growing economies, with an average annual growth rate of about 8% as the fruits of several factors such as political and macroeconomic stability, rebound in post-war economic activity, more Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into the extractive industries and post-war reconstruction.[1] During this period, important gains have been achieved, such as reduced maternal and child mortality rates, increased access to basic education services for girls and boys, water and electricity. Around one-third of the population now has access to electricity, compared to barely 4% in 1998, and over the last decade, new HIV cases have fallen by 34% and AIDS-related deaths by 27%.[2] The combination of these results is reflected in the improvement of the life expectancy of Mozambicans from 51 years in 1992 to about 61 in 2021.

Yet, the country faces significant development challenges. It is among the poorest countries in the world, with a GDP per capita of US$447 (market exchange rate) or US$1 243 (purchasing power parity (PPP)) in 2022, only ahead of Somalia, Central African Republic, Burundi and South Sudan in Africa. According to the latest estimates, by the end of 2022, 71% of Mozambicans lived below the international poverty line of US$2.15 per day[3] and the country is among the most unequal in sub-Saharan Africa. In its 2021/2022 report, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) classified Mozambique as a country with low human development, with a score of 0.446 (out of 1) on the Human Development Index (HDI). Mozambique ranks 185th out of 191 countries, far below its neighbours.

The post-2015 growth has been slow (averaging 3% between 2016 and 2022) amid the ‘‘hidden debt’’ scandal which coincided with a series of shocks, including an insurgency in Northern Mozambique, tropical cyclones and the Covid-19 pandemic, while unemployment, poverty and inequality have increased.

The previous decade of high growth rates was not accompanied by structural transformation and industrialisation of the economy, which continues to rely heavily on the extractive sector, with limited linkages with the rest of the economic sectors, and a low-productivity agriculture sector, which is extremely vulnerable to weather shocks and climate change. Factors such as inadequate infrastructure, ineffective policy implementation, corruption and a poor business environment constrain economic diversification and the quality of growth.[5]

The government is now faced with a pressing question of how to achieve long-term sustainable and inclusive growth to ensure steady reductions in income inequality and extreme poverty. Expectations from the gas megaprojects in its northern provinces to transform the country’s future are high. However, experience elsewhere in Africa has shown that natural resource extraction has rarely lived up to its promise, often doing more harm than good. Translating growth and revenue from natural resource extraction into improved and inclusive development outcomes requires visionary leadership and developmentally oriented governing elites to carefully manage and invest the revenue in sustainable economic and human development.

The Mozambique National Development Strategy or Estratégia Nacional De Desenvolvimento (ENDE) 2023-2043 guides the country's development process, aiming to achieve a long-term vision for the country. Its objectives include improving the country's infrastructure, increasing productivity and competitiveness, promoting economic diversification, promoting access to basic services, promoting social inclusion, strengthening governance and transparency, as well as environmental sustainability to increase the country's productive capacity, the population's living conditions, and reduce social and regional inequalities. To achieve these objectives, the ENDE is structured around five main pillars: (i) Structural Transformation of the Economy; (ii) Social and Demographic Transformation; (iii) Infrastructures; (iv) Governance; and (v) Environment and circular economy. Each pillar has strategic objectives, result indicators and targets for the period 2023-2043.

This report complements the Mozambique Growth Diagnostic Study conducted by the London School of Economics (LSE) Growth Diagnostic Lab which analyses the country’s past and current socio-economic situation as well as the key binding constraints to inclusive growth. We take a forward-looking approach to analyse the likely future of Mozambique along the Current Path forecast (or business-as-usual scenario) and answer the following questions: What are the trends that have shaped modern Mozambique, and how do they compare with trends for other countries at similar levels of development? Given the current policies, environmental conditions and future revenues from megaprojects in gas, what would the situation be in 2043, in line with targets in Mozambique’s National Development Strategy 2023-2043? This report explores a series of sectoral scenarios to emulate their comparative and cumulative effect towards sustained, inclusive growth and development in Mozambique.

[1] The World Bank, Poverty Reduction Setback in Times of Compounding Shocks: Mozambique Poverty Assessment, June 2023.

[2] UK–Mozambique development partnership summary, Policy paper, July 2023

[3] Salome Ecker et al.(2023), the impact of the cost-of-living crisis on poverty in Mozambique and possible policy responses, United Nations Development Programme.

[5] Neil Balchin et al (2017). Economic transformation and job creation in Mozambique, Synthesis paper.

The foresight analysis in this report relies on the International Futures (IFs) modelling tool, developed by the Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures at the University of Denver, United States. IFs is a tool for thinking about long-term, country-specific, regional and global developments. The model integrates forecasts across many sub-models, including demographics, economics, health, education, infrastructure, agriculture, energy, technology, governance, international politics, socio-political issues and the environment. These sub-models are dynamic and integrated, allowing for simulations that demonstrate how changes in one system can lead to changes across all other systems. The scenario analysis capabilities of IFs allow users to explore the potential impact of simulated policy interventions or to frame long-term uncertainty within and across development systems.[x]

IFs models development for 189 countries and their interaction, including 55 countries in Africa that can be combined to analyse and forecast the future of any group of countries. It blends different modelling techniques to form a series of relationships based on academic literature to generate its forecasts. IFs uses historical data from 1960 (where available) to identify trends and to produce a 'Current Path forecast' scenario from 2019 (the current base year). The Current Path is a dynamic scenario representing a continuation of current policy choices and technological advancements and assumes no significant shocks or catastrophes. It moves beyond a linear extrapolation of past and current trends by leveraging our available knowledge about how systems interact to produce a dynamic forecast. Currently, IFs is one of the few global modelling platforms capable of projecting Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) achievement across many of the SDGs at the country level,[1] and has been widely used in the analysis of African development.[2]

The data series within IFs come from a range of well-known sources such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Health Organization (WHO) and various United Nations (UN) bodies like the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and United Nations Population Fund (UNPF), etc. These organisations collect and standardise data which is essential for cross-country comparisons.

The project uses an additional project data file with updated key data series as supplied by the various Mozambican authorities. The data series that was adjusted for this study is presented in an annexure to this report.

This report uses Africa's low-income countries as a benchmark for gauging Mozambique's historical and future progress. Where appropriate, Mozambique is compared to regional peers.

For this study, we adjusted the Current Path to account for the gas project, given its potential impact on development prospects based on research and consultations with gas experts, economists and government officials during a consultation meeting in Maputo.

In 2010, Mozambique made significant discoveries of natural gas totalling approximately 150 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) in the adjacent blocks of Area 1 and Area 4 within the offshore Rovuma Basin, situated off the northern Cabo Delgado province. This positioned Mozambique as Africa's third-largest holder of natural gas reserves, following Nigeria and Algeria.[1]

TotalEnergies and its consortium partners are set to exploit the liquefied natural gas (LNG) field in Area 1, known as the Offshore Area 1 Golfinho/Atum gas field, located in Mozambique’s deepwater Rovuma Basin. The investment for this endeavour is estimated at US$20 billion. Area 4 comprises two projects: the onshore Area 4 Mamba field and the offshore Area 4 Coral South field, controlled by a consortium primarily led by ExxonMobil and ENI, with an estimated investment of US$30 billion (combining onshore and offshore components).[2] Notably, the final investment decision for the Area 4 Coral South field (offshore) is pending, with experts predicting it will be between 2025 and 2026.

Given the significant delays in gas exploitation, the timeline for gas production and the estimated associated revenue is highly uncertain. Revenue projections vary significantly depending on assumptions, especially the LNG sale price. In 2018, the Government of Mozambique (GOM) estimated that government revenues from both areas would range between US$35 and US$63.6 billion over the lives of the two projects, with the likely figure (its base case scenario) being around US$49.4 billion. Importantly, government revenue would only significantly increase from 2032 as the LNG deals have been structured so that in the initial years, revenue goes mainly to foreign companies to help them recoup their investments.[1] In contrast, an independent government revenue forecast by the company Open Oil in 2021 put it at around US$18.4 billion, with a substantial portion expected after 2040 (70%).[2]

Uncertainties surrounding revenue projections stem from factors like volatile international gas market prices, currency fluctuations, competition from established producers, and global goals aimed at reducing fossil fuel reliance. If this latter ambition is realised, LNG's value will fall, making government revenue far less than anticipated. Overall, projections of LNG revenues are difficult to forecast and sometimes unreliable.

Against this backdrop, we consider the GOM’s estimated revenue in its base case scenario (US$49.4 billion). A recent study of 12 African countries which exploited oil and gas resources between 2001 and 2020 found that revenue forecasts were exaggerated in all 12 cases by an average of 63%.[3] A more conservative approach in this study models 37% of the estimated revenue in the base case scenario, which is US$18.3 billion, in line with Open Oil’s estimation of about US$18.4 billion. Based on the 2018 GOM estimation, the total gas production is expected to be around 3.5 billion barrels of oil equivalent (BBOE) over the project lifetime (2023-2048).

Agriculture, mining, and energy form the foundation of Mozambique's modest economy. From 1992 until 2015, the country consistently ranked among the world's top 10 fastest-growing economies. However, the revelation of undisclosed debts in 2016, commonly referred to as "hidden debt", precipitated a sharp decline in growth, triggering an economic governance crisis and a prolonged deceleration in economic activity, with growth plummeting from 6.7% in 2015 to an average of 3% between 2016 and 2019. This growth slump was further compounded by the compounding impact of natural disasters in 2019, the insurgency in Northern Mozambique escalating since 2017, the global pandemic in 2020 and the Russian–Ukraine war with its associated high energy and food prices.

Going forward, Mozambique's growth prospects look positive. The LNG production and the associated revenue for the GOM are expected to boost GDP growth rates, although at risk from climate-related shocks and uncertainty around the security situation in the North despite recent improvements and macroeconomic instability. The total public debt is forecast to stabilise at about 92 per cent of GDP in the medium term.[1]

The IFs economic model draws on both the classical tradition of focus on economic growth with great attention to the newer work on endogenous growth theory and the neoclassical perspective of the general equilibrium approach. The supply side of the economic model is based on the Cobb–Douglas production function and uses labour, capital and multifactor/total factor productivity as the primary drivers of economic growth. Multifactor or total factor productivity in the model is determined by human capital (education and health), social capital (governance effectiveness, corruption and economic freedom), physical capital (infrastructure) and knowledge capital (R&D spending and knowledge diffusion from trade integration). Each of these four categories contributes positively or negatively to economic growth.

Looking across the main determinants of multifactor/total factor productivity, the model shows that physical capital (infrastructure) is currently Mozambique's most significant constraint on productivity growth. This is due to the country's poor infrastructure, and the finding is in line with the conclusion of the recent Mozambique Growth Diagnostic Study conducted by the London School of Economics (LSE) Growth Diagnostic Lab.[3] On the current development trajectory, the infrastructure deficit is expected to remain the biggest drag on productivity growth in the country until at least 2043.

Due to the delay in gas exploitation, the benefits of the megaprojects in terms of economic growth will probably materialise beyond our forecast horizon (2043). Under a business-as-usual scenario incorporating LNG, the average growth rate between 2023-2034 will be 5.8% compared with 7.1% over 2035-2043. The average growth rate between 2023 and 2043 will be 6%, 3.2 percentage points below the expected 9.2% in the GOM's optimistic scenario over the same period in the National Development Strategy (2023-2043). As a result of these expected positive growth rates, Mozambique's GDP (2017 constant US$) will triple from US$15.7 billion in 2023 to US$48.2 billion in 2043, about US$7 billion larger than the US$41 billion projected under a scenario without natural gas resources in the same year.

In 2023, Mozambique had Africa's 7th lowest GDP per capita (PPP). As shown in Chart 4, Mozambique significantly reduced the gap between its GDP per capita and the average for its income peers in Africa between 1995 and 2015, reflecting the high growth performance recorded over this period. The gap has started to widen again due to the post-2015 poor growth performance and elevated population growth.

On the Current Path, Mozambique will likely not close the gap with the average for its peers as its real GDP per capita (2017 PPP) will increase by 64.7%, from US$1 300 in 2023 to US$2 141 by 2043, below the average of 3 254 for low-income Africa, and US$215 larger than the GDP per capita of US$1 927 under a scenario without natural gas resources in 2043. As for the real GDP per capita (market exchange rate), it increases by 87% from US$465 in 2023 to US$870 by 2043, about half of the US$1 610 for low-income Africa in the same year. The increase in Mozambique's GDP per capita between 2023 and 2043 will remain modest compared to the increase in GDP over the same period. High population growth means economic growth rates translate into smaller per capita income increases.

Mozambique has seen a limited shift in the structure of its economy. The existing growth model, which relies heavily on large extractive projects, has not generated inclusive growth through the provision of employment opportunities.

The extractive sector is heavily dependent on megaprojects that do not create employment opportunities for many Mozambicans, with the majority of the economically active population remaining in the agricultural sector. Only 58% of the working-age population is economically active. Of those who are employed, 66.8% still practice primary activities (agriculture, forestry, fishing and mining), and only 4.5% are employed in the manufacturing, energy and construction industries. The service sector (transport, communications, commerce, finance and administrative services activities) absorbs the remaining 12.8%.[1]

Like many other low-income countries, the size of the informal economy is very large in Mozambique. In 2021, Mozambique had around a 96% informality rate among its workforce. Countries with high informality have a whole host of development challenges, such as low revenue mobilisation. Economic growth tends to be below potential in countries with high levels of informality. A recent study conducted in Mozambique shows that compared to formal micro enterprises, informal firms sell about 14 times less, make 17 times lower profits and are 2-3 times less productive.

As of 2023, the size of the informal sector in Mozambique was equivalent to 36.5% of its GDP. On the Current Path, informality will decline to about 30% of GDP by 2043, above the average of 26% for African low-income countries and 18.4% for Southern Africa.

Our fieldwork revealed that the time, fees and cumbersome paperwork needed to register a business and the lack of information and training to comply with rules are some of the key factors preventing the formalisation of informal firms. The interviews indicated that some government officials do not know the regulations and ask for more documents than needed to register a business, a practice that discourages formalisation. The formalisation of informal enterprises to boost the Mozambican economy and tax revenue should be gradual as the informal sector is currently the lifeblood of the growing population of young Mozambicans in the absence of formal sector opportunities. The GOM should start by highlighting what these informal firms get from formalising (i.e. support such as credit and training to grow, market from big formal firms, etc.) and training government officials in charge of registering businesses.

The IFs forecasting platform relies on international measures for extreme poverty. Thus, we use the US$2.15 per day poverty line (2017 PPP), unless otherwise specified, to remain consistent with international poverty analyses. As such, the poverty rates reported here differ from the poverty rates measured using the national poverty line, which was MZN 40 per day as of 2020.

Using the poverty threshold of US$2.15, Mozambique had the fourth highest poverty rate at 71% among the 22 low-income countries in Africa in 2022. Chart 6 shows the past trends in poverty and projections on the Current Path. It indicates that poverty is not a new phenomenon but a long-standing issue in Mozambique. The downward trend of the poverty rate in the 1996/1997-2014/15 period has been reversed, and poverty rose from 64.6% to 71% in 2022, erasing the important gains in poverty reduction of the preceding decade. Yet, the number of people living in extreme poverty in Mozambique has consistently increased from 13 million in 1996 to nearly 17 million in 2014 and 23 million people in 2022.

The period following 2015 witnessed pronounced economic volatility, both domestically and globally, resulting in a significant reversal in poverty reduction. Various shocks, including the hidden debt crisis and subsequent macroeconomic instability, led to a notable deceleration in economic growth. This situation was exacerbated by the impact of severe cyclones Kenneth and Idai in 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis induced by the onset of the war in Ukraine in early 2022. By the end of 2021, before the beginning of the Ukraine war and the cost-of-living crisis, extreme poverty (<US$2.15/day) was estimated at 67.9% of the Mozambican population (about 21 million people). About 3.3% of Mozambique’s population was classified as extremely poor in 2022 compared to a year before due to elevated food, energy, and transport costs. This represents a 4.8% increase in extreme poverty rates in Mozambique during this period, reaching 71% by the end of 2022.[1]

Poverty in Mozambique disproportionately affects young people, women, individuals with lower education levels, residents of larger rural households, and those working in the agricultural sector. Geographically, provinces in the Northern and Central regions of the country are hardest hit by poverty. In contrast, the Maputo Province and Maputo City in the South have the lowest poverty rates, standing at 22.4% and 11.4%, respectively.

In the Mozambique National Development Plan (ENDE), the target is to reduce the proportion of the population living below the national poverty line from 68.2% currently to 35.8% by 2043. On the Current development trajectory, the poverty rate in Mozambique (at US$2.15) will reach 44.9% by 2043, about 25 percentage points above the average of 21.2% for low-income Africa in the same year. The number of poor people will peak at 32.5 million in 2030 due to population growth before steadily declining to 24.8 million by 2043. Under the Non-LNG trajectory, the poverty rate will be 52.3%, equivalent to 29 million people.

Even with the significant boost to economic growth from natural gas production, Mozambique will likely have almost the same number of people living in extreme poverty in 2043 as it has today. For growth to contribute effectively to poverty reduction, it needs to happen in a way that benefits the poor. The production of gas may generate jobs, but not many will be permanent. On a business-as-usual pathway, Mozambique will miss the SDG target of eliminating extreme poverty by 2030 by a substantial margin.

Mozambique’s historical and continuing burden of poverty is largely a function of its population growth rates, the limited access to education, health and basic services, especially in rural areas, low productivity and lack of resilience against climate disasters in the agriculture sector, poor infrastructure, recurrent natural disasters in some regions and persistent high level of income inequality which negatively affects social cohesion.[3]

Even though income inequality slightly decreased over the period 2015-2020, Mozambique remains among the most unequal countries in sub-Saharan Africa. The Gini coefficient is a standard measure of the level of income inequality. In 2019, the national Gini coefficient was 0.50 (out of 1.00) compared to 0.54 in 2014. Often, the implicit assumption in poverty reduction strategies is that poverty reduction will come through growth, i.e., the benefits of more rapid economic growth will trickle down to reduce poverty. While economic growth is necessary, it is not sufficient for poverty reduction as levels of inequality matter. Higher levels of inequality have been shown to undermine the poverty-reducing effect of economic growth.[4] This is because an initial maldistribution of physical, human and financial resources makes it much harder for poor people to participate in and therefore gain from the proceeds of economic growth. Public expenditure and investment have been unevenly distributed across the regions, with the wealth concentrated in the southern region, especially Maputo.

Without tackling inequality, economic growth will have little effect on poverty reduction in Mozambique. The ENDE (2023-2043) identified inequality as a challenge, and the target is to reach a Gini coefficient of 0.3 by 2043. Chart 7 shows how income inequality might evolve going forward on the Current Path.

On the Current Path, the Gini coefficient for Mozambique by 2043 will be 0.43, above the target of 0.3 and the average of 0.38 for low-income Africa. To achieve the objective of inclusive wealth creation, the GOM must commit to policies that redistribute the benefits of economic growth to all. To this end, Mozambique will need to tackle corruption, create more jobs, address gender inequalities in access to goods and services, scale up social safety nets, and address the targeting challenges, among other things.

The GOM has implemented various social protection initiatives and programs aimed at supporting individuals facing poverty and vulnerability. They include cash benefits for seniors and individuals with disabilities and chronic illnesses and aid for vulnerable groups such as malnourished children, orphans, and those with HIV, alongside public works initiatives and social services. The largest social assistance program, the Basic Social Subsidy Programme (PSSB), primarily enrols elderly individuals (91.5%), followed by those with disabilities (5.9%). Women comprised 64.7% of social assistance beneficiaries in 2022. With over 90% of tax revenues in 2021-22 absorbed by the wage bill and debt-service costs, the country will struggle to allocate more resources to social spending.

Developmental sectors: Current Path and scenarios

Download to pdf- Briefly

- Governance and stability in Mozambique

- Governance scenario

- Demographics and health in Mozambique

- Demographics and Health scenario

- Education in Mozambique

- Education scenario

- Infrastructure in Mozambique

- Infrastructure scenario

- Agriculture in Mozambique

- Agriculture scenario

- Manufacturing in Mozambique

- Manufacturing scenario

- International trade in Mozambique

- Free Trade (AfCFTA) scenario

- External financial flows in Mozambique

- Financial Flows scenario

This section provides an overview of eight development sectors along Mozambique's current development trajectory and the impact of a single optimistic scenario associated with each. The eight sectors and scenarios are: Governance, Demographics and Health, Education, Infrastructure, Agriculture, Manufacturing, International trade (the implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area), and External Financial Flows.

Because the new GOM that will be elected this year, will need time to settle in before rolling out its development programme, the policy interventions within each scenario commence in 2026 and present a subsequent 10-year push to 2035, with the improvements maintained to 2043.

The various interventions in the scenarios are based on a careful calibration of what is realistically possible. This is based on comparisons of what has been achieved by countries at similar development levels to Mozambique through a benchmarking process (see Annexure). The interventions are an optimistic view of Mozambique’s future. The objective is to highlight policy interventions needed to accelerate human and economic development in Mozambique.

Good governance is key to economic progress. Greater security and stability at the national level create an enabling environment for domestic and foreign investment. It creates conditions in which governments can pursue effective, sustainable development strategies. Good governance and security cut across all sectors; they create incentives and confidence for investment and innovation. Good governance is crucial for the efficient use of public funds for development and improving the well-being of the population.

Mozambique has a long history of military and political instability. In recent years, the country has dealt with armed conflict and insurgency, particularly in the northern province of Cabo Delgado, where militant Islamist groups have been active. Yet, it has consistently conducted multiparty presidential, parliamentary and provincial elections since the end of the civil war in 1992. Tensions remain between its three main political groups: the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (Frelimo), the Mozambican National Resistance (Renamo), and the Mozambique Democratic Movement (MDM), and the quality of the elections has deteriorated over the years. Discussions with experts during our field trip highlighted that the quality of democracy in the country has been deteriorating along with the decline in the rule of law in recent years. The political environment is highly polarised; institutions are weak and instrumentalised by political parties, while decentralisation, which was supposed to improve public service delivery rather, serves to accommodate political interests.

Poor governance remains at the root of many citizens' frustrations and grievances among various groups in the country; civil service capacity is low, and the perception of financial corruption by Mozambique’s political elite is high, as evidenced by the 2016 clandestine loan. Despite strong economic growth, many Mozambicans feel left behind in the country’s development, and the growing discontent within the young population is a concern for the country’s long-term democratic stability. According to the 2022 Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) report, overall governance in Mozambique has deteriorated over the last decade. The country ranked 26th of 54 African countries on the Index, with a score of 48.6 out of 100, lower than the regional average for Southern Africa (54.2).

Corruption indicators have been progressively deteriorating in Mozambique. During our interview with the civil society in Maputo, one participant indicated that corruption is ’the single biggest obstacle to the country’s future.’ According to the 2022 global Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) by Transparency International, Mozambique, with a score of 26 out of 100, occupies 142nd position out of the 180 countries surveyed, compared with a score of 31 in 2012. This is in line with findings from other governance and perception of corruption indices, including the survey of business leaders by the World Economic Forum. On the Current Path, the score for Mozambique on the CPI will be 3.1 out of 10 or 31 out of 100 in 2043, on par with the average score for low-income African countries but below the target of 51 out of 100 in the National Development Strategy in the same year.

The high level of corruption in Mozambique undermines government effectiveness in service delivery. In IFs, the governance effectiveness index by the World Bank is rescaled to 0 to 5 (with higher values corresponding to better outcomes) instead of from −2.5 to 2.5. With a score of about 1.7 out of a maximum of 5 in 2023, Mozambique ranked 31 of 54 countries in Africa in terms of government effectiveness. A patronage political culture that often relies on the provision of benefits and public goods in exchange for political support and weak institutions are some of the underlying factors of this progressive deterioration in governance and corruption in Mozambique.[4]

An increasing body of literature shows that weak governance and corruption severely hamper economic performance and development. Good governance will therefore be crucial for achieving the objectives of the National Development Strategy (2023-2043). In the National Development Strategy, the operationalisation of the governance pillar will focus on transparency, democratic participation, efficiency in public administration, modernisation, responsibility and the fight against corruption, creating an environment conducive to investment and sustainable development.[5]

On the Current Path, governance indicators will improve slightly by 2043 compared to their levels in 2023 but will remain below the averages for Southern Africa (Chart 8).

In IFs, governance can be analysed along three dimensions – security, capacity and inclusion – reflecting the traditional sequencing of the state formation process. The score for each dimension ranges from zero (bad) to one (excellent). The security dimension measures the probability of intra-state conflict and the general level of risk. The second dimension, capacity, is related to government revenue, corruption, regulatory quality, economic freedom, and government effectiveness. The third dimension, inclusiveness, measures the level of democracy and gender empowerment.[1]

Mozambique performs poorly in capacity compared to other dimensions of governance, reflecting the weak government revenue and government effectiveness, high corruption, and poor regulatory quality. On the Current Path, Mozambique will make progress in all three dimensions of governance (security, capacity and inclusion). As a result, the country's score on the composite governance index, which is a simple average of the three dimensions of governance mentioned above, will be about 20% higher in 2043 than its level in 2023.

Efforts to achieve lasting stability and security and improve governance and democracy in Mozambique will likely require sustained efforts addressing underlying socio-economic grievances, promoting inclusivity, and strengthening institutions.

The Governance scenario represents a reasonable but ambitious improvement in governance in Mozambique. The scenario reduces the probability of internal conflict and societal violence (security), reduces corruption, increases economic freedom, and enhances governance effectiveness and regulatory quality (capacity). It finally improves the level of democracy and gender empowerment (more inclusion).

Under the governance scenario, Mozambique's score on the composite governance index will improve by about 30% over the period 2023-2043 compared with 18% on the Current Path over the same period.

If the governance scenario were implemented, Mozambique could experience large gains in economic growth and poverty reduction. Indeed, the size of the economy would be US$ 5 billion larger in 2043 than on the Current Path. The average Mozambican is expected to gain US$151 in GDP per capita (PPP) in 2043 compared to the Current Path of US$2 141. There will be 2.4 million fewer Mozambicans surviving on less than US$2.15 per day in 2043 compared with the Current Path of 24.8 million people in the same year. This is equivalent to a monetary poverty rate of 40.4% against 44.9% on the Current Path in 2043.

There are strong interactions between population and health. The status of a country’s health influences levels of fertility, mortality and morbidity. At the same time, high population growth contributes to an increased need for basic necessities for life, such as nutrition and health.

Demographics

The characteristics of a country’s population can shape its long-term social, economic, and political foundations; thus, understanding a nation’s demographic profile indicates its development prospects. Since 2000, Mozambique’s population has increased by about 70% from 18 million to about 32.9 million in 2022, making it the 14th largest population in Africa and the 3rd largest in the southern African region after South Africa and Angola.

On the Current Path, Mozambique’s population is expected to reach 55.4 million people by 2043, reflecting the reduction in mortality and elevated fertility. The average population growth rate between 2023 and 2043 will be 2.5%, which is significantly above the target of 1.8% set out in the National Development Strategy (ENDE) over the same period. In 2043, Mozambique's population growth rate will be 2.1%, on par with the average for low-income Africa but above the target of 1.3% set out in the ENDE for that year (Chart 10).

The total fertility rate in Mozambique peaked in 1972 when the country recorded 6.7 births per woman — the 29th highest in Africa. Since then, the fertility rate has been declining, albeit slowly. This decline, in part, can be attributed to a decline in child and youth mortality, greater access to education, and family planning services. According to the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) 2022/2023, 26% of currently married women ages 15–49 and 47% of unmarried women sexually active use some method of family planning.

Despite this promising trend, the current fertility rate of 4.6 births per woman, while slightly below the estimated average of 4.9 births per woman for Africa low-income countries, remains unfavourably high. The fertility rate is not homogenous across the country. On average, the women in rural areas have 5.8 children compared with an average of 3.6 children in urban areas. The percentage of modern methods of contraception used among currently married women aged 15-49 is higher in urban areas (40%) compared to rural areas (18%). In relation to the provinces, Zambézia (11%), Nampula (13%) and Cabo Delgado (14%) have the lowest percentage of currently married women using some modern methods.[1]

The GOM has reiterated that the management of population growth is a critical priority in order to meet the country’s social and economic development goals. This is currently prioritised as a focus area in the ENDE. On the Current Path, the total fertility rate in Mozambique is expected to be 3.1 births per woman in 2043, below the average of 3.4 for African low-income countries and above 2.8 for Southern Africa.

High fertility rates coupled with low life expectancies resulted in Mozambique having one of Africa's most youthful age structures. The median age was 16.8 years in 2021 (the latest available data), the thirteenth lowest in Africa. Yet, this is an increase from 15.5 years at the end of the civil war in 1992, indicating a transition in Mozambique’s age structures, albeit slowly. The Current Path shows that the median age in 2043 is likely to be 21.8 years, meaning that half of the population will be younger than 22 years. This gradual ageing of the population is most noticeable in the decline in the population below 15 years, with associated growth in the economically active age groups (Chart 12).

In 2023, about 43% of the Mozambique population was below the age of 15 years. This large cohort of children below 15 years of age requires huge investment in education and healthcare infrastructure. With an expected drop in fertility rates by 2043, 35.8% of the population will be below 15 years of age. The increase in life expectancy is evident in the growing elderly dependent population group, which is expected to increase from 2.8% in 2023 to 4.1% by 2043.

The working-age population cohort (between 15 and 64 years) is expected to increase from 54% in 2023 to 60% by 2043. Properly educated and skilled, this growing workforce can contribute to innovation, entrepreneurship, and economic diversification, allowing Mozambique to enter a potential demographic window of opportunity by 2050. The demographic dividend or demographic gift can be defined as the economic growth generated by the change in a country’s demographic structure. It generally materialises when a country reaches a ratio of at least 1.7 people of working age (15-64 years of age) for each dependant (children (0-14 years) and elderly people (65+ years). The ratio was 1.16 in 2022 and will be 1.5 by 2043 and 1.7 in 2050.

When there are fewer dependants to care for, it frees up resources for savings and investment and eventually allows women, in particular, to pursue careers, skills, and training and increases female labour force participation in a way that they aren’t able to if they are caring for large families.

Studies have shown that about one-third of economic growth during the East Asia economic miracle can be attributed to the large worker bulge and the relatively small number of dependants.[2] However, the growth in the working-age population relative to dependents does not automatically translate into rapid economic growth unless the labour force acquires the needed skills and is absorbed by the labour market. Currently, only 58% of the working-age population in Mozambique is economically active.[3]

Mozambique has a large youth bulge at 49%, which, on the Current Path, is expected to slightly decline to 44.5% by 2043. A youth bulge, defined as the percentage of the population between 15 and 29 years old relative to the population aged 15 and above, exhibits a strong relationship with upsurges in violence, and socio-political instability in poor countries, particularly when opportunities are scarce, education quality is low and democratic expression is inhibited.

Together with population growth and structural demographic changes, Mozambique is expected to see a dramatic shift towards urban areas. Mozambique is one of the least urbanised in the world, with 61% of its population dwelling in rural areas as of 2023. On the Current Path, the urban transition is expected to get momentum, with 49.4% of the population in urban areas and 50.6% in rural areas. Urbanisation is critical to economic growth and development as it fosters entrepreneurship and increases productivity. Cities in Africa generate between 55% and 60% of the continent’s GDP.[4] Despite constituting only about 5% of the country’s population, Maputo is responsible for about 20% of Mozambique’s GDP. Urbanisation can reduce poverty and provide several social and economic benefits when managed sustainably.

Health

Despite efforts to improve Mozambique’s public health sector, the sector remains one of the least resourced in the world which has negatively affected the GOM's ability to improve its population's healthcare. As a result, Mozambique has some of the worst healthcare statistics in the world. In 2019, the country ranked 184th for overall health efficiency among 191 World Health Organisation (WHO) member states, with a low score of 0.26 out of 1.0.[1]

The country has a ratio of only three doctors per 100 000 people, a proportion that is among the lowest in the world. Systems for tracking, motivating and retaining staff are weak, and frontline health providers are often poorly trained and have limited management skills. For those in rural areas and the extremely poor, women, adolescent girls, and children, quality healthcare is very unsatisfactory and hard to reach, exposing health system inequalities between genders and geographic regions.[3]

Shown in Chart 14, Mozambique spends less money on health care, relatively, compared to its peer countries, although its spending on health has been on an increasing trend since 2014. According to the WTO data, in 2021, Mozambique spent about 8.2% of its total government expenditure on health care, slightly above the figure in 2020 (7.3%).

The efficiency of a country's health system can be assessed through several indicators, such as maternal mortality, infant mortality and life expectancy. Mozambique has made significant progress in reducing mortality rates and improving access to primary health services. It has lower maternal mortality ratios than the average for low-income African countries, and for the Southern Africa regional peers, 112 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births in 2022 compared to an average of 384 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births for low-income Africa and 190 for its Southern Africa regional peers. The SDG target for maternal mortality (SDG 3.1) is a ratio of fewer than 70 deaths per 100 000 by 2030, a target that will likely be attainable on the Current Path trajectory of the country with a ratio of 68.4 deaths per 100 000 live births in 2030 and 44.9 by 2043.

Although Mozambique's life expectancy has improved from 35 years in 1960, it is still below the average of its peers. At 61.8 years in 2022, Mozambique’s life expectancy was about two years lower than the average for low-income African countries and nearly 0.8 years lower than the average of its Southern African peers. Life expectancy will improve over the forecast horizon, surpassing its peer's averages by 2036. By 2043, the country’s life expectancy will reach 70.7 years, 1.2 years above the GOM target in the same year, 0.7 years above the average for low-income countries and 1.3 years above the average for its regional peers.

In 2022, Mozambique’s infant mortality ranked among the highest in lower-income countries in Africa, with 49.9 deaths per 1 000 live births. The SDG target regarding the infant mortality rate is below 25 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2030. On the Current Path, Mozambique is not on track to achieve this target as it will have an infant mortality rate of 39 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2030 and 23 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2043, significantly below the GOM target of 35 deaths per 1 000 live births (see Chart 16).

The combination of low life expectancy and high infant mortality is often a result of high levels of communicable disease prevalence. The death rate from communicable diseases in Mozambique stood at about 4.9 per thousand, 23% higher than the average low-income African country (4.0 per thousand) and 18% higher than the average of its regional peers (4.2 per thousand) in 2022. The cohort death rate distribution (Chart 17) shows that most premature deaths in Mozambique occur in the early stages of life and are heavily skewed toward communicable diseases. Even in the working age groups, communicable disease deaths dominate. AIDS is by far the largest burden in both the 30 to 44 and 45 to 59 years of age cohorts.

Much of the communicable disease burden for infants and 1 to 4 years of age is the result of a lack of health infrastructure. The use of traditional fuel sources (i.e., coal, dung) is a core driver of childhood pneumonia and other respiratory infections. Lack of health facilities for malaria testing and treatments and low bed net use contribute to Mozambique’s high malaria burden. Meanwhile, poor water and sanitation access is a core driver of communicable disease deaths (such as diarrhoea) for children under five years of age. This high communicable disease prevalence in under five years of age can also lead to undernourishment and stunting.

The prevalence of malnutrition has remained high in Mozambique, with 38% stunting and 6% wasting among children under five years of age. Around 209 250 children aged 6-59 months suffer from acute malnutrition, and 72 199 cases of acute malnutrition in pregnant (or lactating) women were recorded between May 2023 and March 2024. On the Current Path, the stunting rate of children under five years of age will decline to 24% by 2043, about 13.8 percentage points above the GOM target rate in the same year in the National Development Strategy (2023-2043)

While Mozambique had a relatively lower burden and peak of HIV/AIDS between the 1990s and 2000s, the country’s prevalence and death rates have decreased much more slowly than most of its peers. Between 2009 and 2012, the AIDS death rate in Mozambique stagnated at around 0.4% of the population and significantly decreased afterwards, reaching 0.2% in 2022. The AIDS death rate reduction will reach 0.05% by 2043, lagging behind most of its regional peers, and Mozambique’s death rates will trail only Lesotho, South Africa and Eswatini.

In the older age cohort (60-69 years age), the disease burden shifts to non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancers. Mozambique will experience its epidemiological transition, a point at which death rates from non-communicable diseases exceed that of communicable diseases, in 2034 (Chart 18). It will be roughly four years later than the average for low-income African countries. This has implications for Mozambique’s healthcare system which will need to invest in the capacities for dealing with this double burden of disease.

The Demographics and Health scenario aims to improve health and advance and increase the size of the demographic dividend. It consists of reasonable but ambitious reductions in child and maternal mortality, increased access to modern contraception, and reductions in the mortality rate associated with both communicable diseases (e.g. AIDS, diarrhoea, malaria and respiratory infections) and non-communicable diseases (e.g. diabetes), as well as improvements in access to safe water and better sanitation.

Under the Demographics and Health scenario, about 73% of fertile women in Mozambique will use modern contraception by 2043, slightly below Rwanda (89.3%) and Malawi (82.4%) in the same year. Population growth will decline to 1.3% compared with 2% on the Current Path, and in line with the GOM target by 2043. As a result, Mozambique is set on a different demographic path, where it converges with the average of its African income peers by 2043. Infant mortality will decline to 13 deaths per 1 000 live births, while the fertility rate will decline to 2.1 births per woman by 2043. If the Demographics and Health scenario is to be implemented, Mozambique could accelerate its demographic transition to reap the demographic dividend by 2041 (Chart 19), ten years later than on the Current Path. Generally, the demographic dividend materialises when a country reaches a ratio of at least 1.7 people of working age for each dependent.

In this scenario, Mozambique benefits from economic growth and poverty reduction. GDP at the market exchange rate (MER) surpasses the Current Path by US$160 million in 2043 while the GDP per capita (PPP) is about US$106 more than the Current Path for the same year. In this scenario, there are 2.7 million fewer Mozambiqucans living in extreme poverty (less than US$2.15 per day) in 2043, equivalent to a poverty rate of 42.8% instead of 44.9% for the Current Path in the same year. This intervention cluster shows that controlling the population growth and investing in health could enhance economic and human development in Mozambique.

The educational system under Portuguese rule in Mozambique had a distinct dual structure. It aimed to provide basic skills to the majority African populace while offering liberal and technical education to the settler community and a small fraction of Africans. The vast majority of students, more than four-fifths, were limited to basic education within this colonial framework. Public education, supported by the state and the Roman Catholic Church, was predominant although private options, primarily affiliated with religious institutions, also existed. Literacy in Portuguese, the primary language of instruction, was limited among the African population at the time of independence.

The introduction of the National System of Education in the early 1980s, aimed at enhancing literacy and technical skills across all age groups, catering to both part-time and full-time students. The nationalisation of private and religious educational institutions facilitated the restructuring and consolidation of the education system. Despite rapid expansion, the state struggled to meet the growing demand for education. Primary school enrollment surged from 643 000 in 1973 to approximately 1.5 million by 1979, but declined in the 1980s due to the destruction of schools by Renamo insurgents. The civil war destroyed critical infrastructure including schools, and prevented meaningful education for the majority of Mozambican older generation.

Only about 63% of the adult population was literate in 2022, which was about 22 percentage points lower than the average for Southern Africa, while only 31% of the adult population (15+ years) completed primary school and nearly 8.1% completed secondary education in 2022.

The current education system in Mozambique is similar to other countries in the region, with schooling comprising three levels starting from primary school and ending at tertiary level. In 2018, the National Education System Law of Mozambique was revised, establishing a new structure in the sector and increasing mandatory (and free) education from seven to nine years. The duration of the education cycles was restructured, reducing primary education from seven to six years and increasing secondary education from five to six years. The law recognises, for the first time, preschool as a sub-sector of education, although it is not a requirement to enter primary school. These changes and more investment and government commitment to keep education expenditure high have led to progress. Yet, efficiency challenges still plague the system and a significant bottleneck between primary and lower secondary schools constrains educational attainment.

Education is a key pillar of human development and productivity and can best be thought of as a pipeline. Children start at the beginning (primary enrolment) and progress through each successive level (lower secondary, upper secondary and possibly tertiary) in the system to emerge with, in theory, appropriate levels and types of education suited to the economic needs of the country. Ensuring that the majority of children make it through key transition points (i.e., from primary to secondary school) is therefore critical.

The GOM has made significant progress in primary school enrolment, increasing the enrolment rate by more than 70% between 1998 and 2018. As a result, Mozambique has a higher primary school enrolment rate than its peers (Chart 20), as primary school is free and compulsory in Mozambique, but barriers like the cost of supplies, preschool malnutrition, gender roles and transport infrastructure limit the ability of students to access and stay in school. In 2022, Mozambique’s gross primary school enrolment stood at 118.7%. Typically, gross enrollment rates being over 100% reflect the presence of students who are not in the age range of the educational levels they are attending.

While the primary school enrolment rate is higher, the human capital for Mozambique remains very low as the completion rate is extremely low. The percentage of enrolled primary students that made it to the final grade of primary was only 51.2%. Thus, although many Mozambican children get into primary school, only about half make it to the end of primary.

There is a significant bottleneck in the transition between lower secondary and upper secondary school. Only 25.1% of students who enter lower secondary school complete it. And only 27.8% of those students who completed lower secondary school move on to upper secondary. This means that the already small pool of students who make it through primary gets even smaller further along the pipeline. The result is that very few students make it to upper secondary. Such lower secondary educational outcomes are some of the key underlying factors of the lower educational outcomes for tertiary levels, which impede progress in poverty and inequality reduction.

The mean educational attainment for adults (15+ years of age) is a good indicator of the stock of human capital in a country but Mozambique has one of the lowest in the world, at 3.9 years in 2022. Mozambique ranked 47th in Africa (out of 54) and 179th globally (out of 186) in the same year.

According to the African Development Bank (AfDB), The low quality of the labour force remains a significant issue both for employers who are unable to engage qualified labourers as well as for promoting a culture of entrepreneurship. The low education level has led some foreign companies to import labour. Recently, the GOM has increased the maximum quota for employing foreign workers as a percentage of the workforce from 10% to 15% for companies with up to 10 employees, and from 8% to 10% for companies with 11-30 employees. The quota remains unchanged at 8% for companies with 31-100 employees and at 5% for companies with over 100 workers. Recently, the GOM has been offering scholarships to its citizens to study abroad - to acquire the required skills, especially in the extractive sector.

Skills mismatches are prevalent in Mozambique. In 2008, between 43% and 8% of the employed were underqualified for the position they held, even as the labour market requires relatively low-skilled labour. The severe lack of skilled labour is not only for managerial positions but also for skilled professionals such as engineers, skilled technicians and accountants. Some companies often import skilled labour. The lack of sufficient skilled labour is, therefore, a major challenge for moving the workforce from low-paying, low-productivity, informal and rural work to the more productive, formal sectors.

The Current Path forecasts that primary enrolment and completion, and secondary enrolment and completion rates will rise over time. The primary completion rate will increase to 84.6% and the lower secondary enrolment rate to 65.3% by 2043. Adults (15+ years) primary education completion rate will increase to 57.4% and 14.8% of adults will complete secondary education. The mean years of education (for adults 15+ years) will increase to 6.2 years, about 0.3 years below the GOM target rate of 6.5 in 2043, while illiteracy will be reduced to 18.8% - about 4.4 percentage points below the GOM targeted rate by 2043. The outcomes and benefits of improving education take decades to manifest and the more children Mozambique can get through primary school and into secondary school now, the better.

Mozambique has a severe gap between male and female educational enrolment and attainment, with the rate of illiterate women being higher than for men. Although Mozambique has recently accelerated its efforts to reduce this gap, girls are still enrolled and completing school at a much lower rate than boys (Charts 22, 23 and 24).

Gender parity in education is seen as a first step toward the ultimate goal of gender equality. Education for girls has been seen to have a positive impact on the economy, for example, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF),[2] crop yields in some African countries would be increased by at least 25% if all women farmers were to receive at least a primary education. In another study, some economies that lack gender equity in education would suffer a 0.1-0.3% reduction in GDP per capita growth rates. The increase in girls' school enrolment rates tends to simultaneously increase boys’ enrolment rates, although the reverse is not always true.[4]

The primary school completion rate is low for female students in Mozambique, with as many as 55% of female students not completing primary education, as of 2022. There will be a cross-over point in 2028 when gross enrolment for girls overtakes boys. Overall, enrolment into both secondary and tertiary education is much lower in Mozambique than its regional peers - Southern African countries’ average, even though there is an upward trend for both males and females.

The economic benefits of educating girls and women include decreased infant mortality, lower HIV/AIDS death rates, increased use of contraceptives and reduced early child marriages. Early marriage for girls poses barriers for female students persisting to the last grade of primary school. Reducing these barriers and ensuring students stay in primary school and receive quality education will help increase primary completion rates and overall educational attainment. The gender disparity gap will close over time and increase in favour of women, as contraceptive awareness and use increases.

The average educational attainment (aged 15+) was 4.4 years for males and 3.3 years for females in 2021. Again, the problem stems from primary school enrolment and completion; only 26.5% of enrolled females make it to the last grade (36.1% for males), and only 6.3% of females complete secondary school (9.7% for males). The average educational attainment (aged 15+) was 4.4 years for males and 3.3 years for females in 2021. Again, the problem stems from primary school enrolment and completion; only 26.5% of enrolled females make it to the last grade (36.1% for males), and only 6.3% of females complete secondary school (9.7% for males).

As a result, Mozambique ranked 37th in Africa on gender parity and had the second lowest gender (after Angola) parity score of any of its regional peers in 2021. While the gender gap will improve by 2043, Mozambique will still have one of the lowest gender parity scores compared to its peers in 2043. While female education is important for a myriad of reasons, there is a key linkage between female secondary education and lower fertility rates.

The quality of education in Mozambique is low. Getting more children into school is essential, but ensuring that they actually learn is more important. Many empirical studies have reported that the quality of education impacts economic growth more than the quantity. The quality of education is usually tracked using Harmonized Test Scores. According to the 2020 World Bank Human Capital Project report, students in Mozambique score 368 on a scale where 625 represents advanced attainment, and 300 represents minimum attainment.

Even though the Mozambique Growth Diagnostic Study[1] has shown that human capital shortage is not an immediate challenge for growth in Mozambique, without efforts to increase the quantity and quality of education, it will compromise long-run economic growth as economic complexity increases.

In the Education scenario, we proceed on the premise that the GOM has recognised the importance of human capital formation for the social and economic well-being of the country and therefore has taken bold actions to improve educational outcomes in the country. For these reasons, this scenario represents reasonable but ambitious improvements in the quantity and quality of education in Mozambique. It improves intake, transition and completion rates from primary to secondary and tertiary levels. It also models substantive progress towards gender parity at all levels, additional vocational training at the secondary school level and increases the share of science and engineering graduates to provide skilled labour to the economy. Finally, the interventions focus on education quality, and reasonable quality improvements are modelled through an improved qualified-teacher/pupil ratio.

The Education scenario increases the overall average educational attainment (for adults 15+ years) level to 6.5 years by 2043 (compared to about 6.2 years in the Current Path), this is in line with the target set by the GOM. The scenario increases primary completion to 95.2% by 2043, compared to 84.6% along the Current Path. As a result, about 61.9% of adults (aged 15+ years) will have completed primary school by 2043. The Education scenario also increases the number of students who enrol and complete secondary school. By 2043, nearly 94% of age-appropriate students will enrol in secondary school (compared to 41% in the Current Path), and 49% of students will graduate from lower secondary school (compared to 41% in the Current Path) and 29% from upper secondary relative to 27% on the Current Path. Adults' literacy rate increases to 83.2%, about 2 percentage points above the Current Path.

In this scenario, Mozambique’s GDP surpasses the Current Path by US$1.65 billion in 2043 while the GDP per capita (PPP) is about US$ 54 more than the Current Path for the same year. In this scenario, there are about 1.3 million fewer Mozambicans living in extreme poverty (less than US$2.15 per day) in 2043, equivalent to a poverty rate of 42.6% instead of 44.9% for the Current Path in the same year.

Education is one of the key enablers for the acceleration of the broad-based growth and development of a country. It is vital for inclusive wealth creation as it improves the job and income prospects of the poor segment of society. The benefits from investment in education in terms of growth and poverty reduction take time to materialise, as it affects labour productivity with a long time lag. The impact of education on growth and poverty reduction also depends on whether the skills are being harnessed through employment.

Infrastructure is generally poor in Mozambique, constraining the growth and diversification of the economy. Infrastructure development has widespread benefits to productivity and human well-being and has many direct linkages to poverty and inequality reduction.

The fact that most Mozambicans reside in rural locations complicates infrastructure provision since it is usually much more cost-effective and easier to provide infrastructure to people in urban areas than in remote rural settings. In 2022, Mozambique ranked 44 out of 54 African countries and lowest in the Southern Africa region on the African Infrastructure Development Index (AIDI), with an index of 13.7 out of 100. The AIDI is developed by the African Development Bank, and is made up of four composite indexes for electricity, transport, ITC, water and sanitation.

Water, sanitation and hygiene

Improved water and sanitation infrastructure improves the human capital stock in a country through its positive impact on health outcomes. Better provision of clean water and improved sanitation will help prevent the spread of communicable diseases, the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in Mozambique. Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WaSH) is an issue in Mozambique due to a declining number of natural water sources, a high amount of contaminated water resources, and lack of proper toileting facilities. These hindrances result in water-borne diseases, unsafe drinking water, bacteria-ridden agriculture and many other challenges. Over half of the country lives without clean water and three in four people have no decent toilet.

In 2022, 73.2% of Mozambicans had access to safe water (an increase from 30.4% in 2002), while the averages for lower-income Africa and global lower income were 74.6% and 76.9%, respectively. In other words, the absolute number of people with access to safe water sources increased from nearly 5.7 million in 2002 to 24.1 million in 2022, a 325% increase over 20 years. Although the improvement is impressive, more needs to be done as nearly 8.8 million Mozambican people still do not have access to safe water sources and rely on unsafe water sources for their needs, exposing them to malnutrition and communicable diseases such as cholera.

On the Current Path, the access rate to safe water will increase to 82.4% by 2043 (Chart 27). This implies that about 9.8 million Mozambicans will still be without access to safe water sources by 2043, as the population grows. The access to improved sanitation rate will increase slightly to reach about 53.8% of the population by 2043. This will continue to cause a high burden of communicable diseases and malnutrition in Mozambique.

Energy and electricity access

Electricity access is critical for socio-economic development, poverty reduction and human well-being. It provides multiple social and economic benefits, from improved industrial capacity, business development opportunities, telecommunications, healthcare and education that directly improve employment. Mozambique has one of the largest electricity generation potentials in Southern Africa and among the highest on the continent, with the potential to become a regional hub, providing opportunities for investment and rapid socio-economic development. It is rich in renewables (hydro, solar, geothermal and tidal) and non-renewable (gas and coal) energy resources with an estimated potential to generate 187 gigawatts of electricity from coal, hydro, gas and wind, with natural gas expected to provide 44% of total grid electricity.

Currently, a large share of its electricity generated is from hydro projects, notably, the Cahora Bassa dam on the Zambezi River which accounts for more than 80% of the national production but much of it is exported to South Africa. The country should be able to meet domestic demand for electricity, however, despite the potential, access to electricity remains low and the national grid is underdeveloped. The GOM has announced that it will end half a century of hydropower supply from Cahora Bassa to South Africa when the current contract ends on 31 December 2030.[3]

In 2021 (most recent available historical data), only 31.5% of the Mozambican population had access to electricity compared to South Africa (89.3%), Zambia (46.7%), Zimbabwe (49%), and 37.3% for the average of its peers (low-income Africa). Mozambique ranked 44 out of 54 African countries for domestic electricity access in the same year.

Mozambique is a net exporter of electricity to its neighbouring countries (Eswatini, Lesotho, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe) with South Africa being the main importer. Yet, Mozambique’s exploitation of energy resources for domestic use remains limited and unevenly distributed. Equally, reliable and sustainable energy access (particularly in rural areas) remains relatively low compared to neighbouring countries (lower than South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe – the country’s importers) while urban areas suffer poor service quality.

Only 3.8% of the rural population had access to electricity in 2021, compared to South Africa (93.4), Zambia (14.5%), Zimbabwe (31.6%) and an average of 22.1% for its peers in 2021. Although Mozambique’s grid has grown it is not dense enough to supply electricity in many rural communities, where over 60% of the population lives. The main challenge is therefore to expand the network - a task that, given the long distances and the distribution of the population over 800 000 square kilometres, will require massive investments.