South Africa

South Africa

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

The page provides an in-depth analysis of South Africa's current and projected future development, examining various sectoral scenarios and their potential impacts on the country's growth. It explores the individual and combined impact of eight sectors including demographic, economic, and infrastructure-related outcomes for South Africa to 2043. The analysis offers insights into policy actions that could enhance South Africa's developmental trajectory.

Please see the Technical Site for more information about the International Futures (IFs) modelling platform we use to develop the various scenarios.

Summary

We begin this page with an overview of South Africa's geographical and political landscape, noting its status as one of eight upper-middle-income countries in Africa and its membership in regional bodies such as the South African Customs Union (SACU) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC). The introduction highlights South Africa's diverse geography and its wide range of climatic conditions. It covers its complex history, from the apartheid era to the transition to democracy in 1994, which brought significant political and socio-economic reforms. It discusses the country's ongoing challenges, including inequality, unemployment, deindustrialisation, and recent efforts to improve investor confidence and infrastructure despite recent political and governance issues.

The introduction is followed by an analysis of South Africa’s Current Path prospects, which informs the country’s likely development trajectory to 2043. It is based on current development trends and assumes that no significant shocks would occur in a ‘business-as-usual’ future. The Current Path suggests that South Africa’s:

- Population is likely to grow from 63.8 million in 2023 to 77 million by 2043, together with a declining fertility rate, an increasing median age from 29.1 years in 2023 to 34.1 years by 2043, and an ageing population with those aged 65 and older increasing from 6.6% in 2023 to 10.7% in 2043.

- Urbanisation will continue to rise, with the proportion of the population living in urban areas increasing from 66% in 2023 to 72% by 2043. This will place pressure on urban infrastructure and services, necessitating substantial investments to accommodate the growth, safely and sustainably.

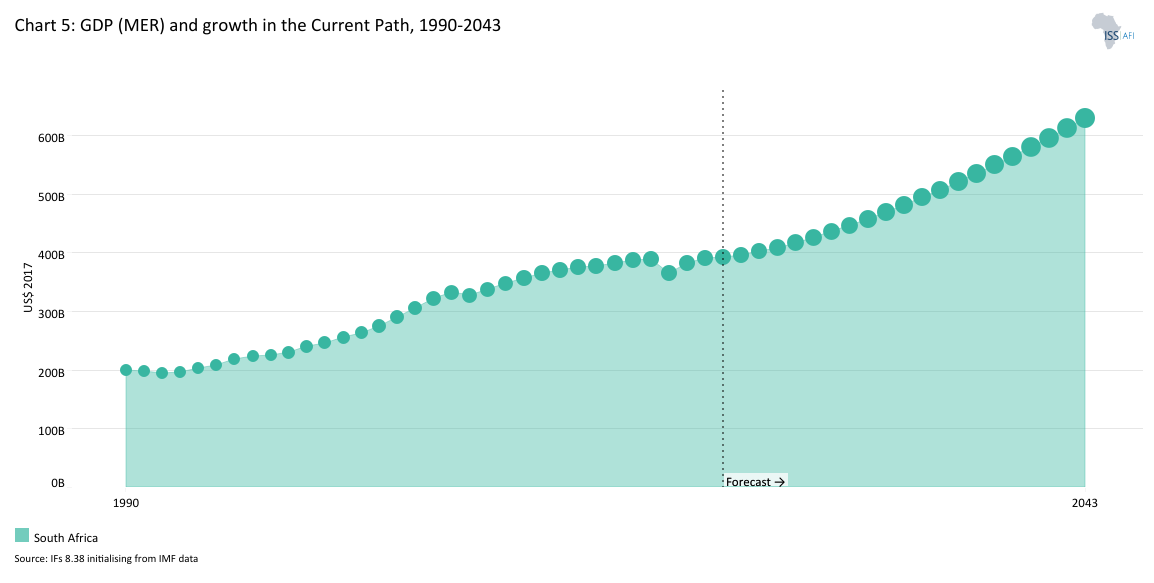

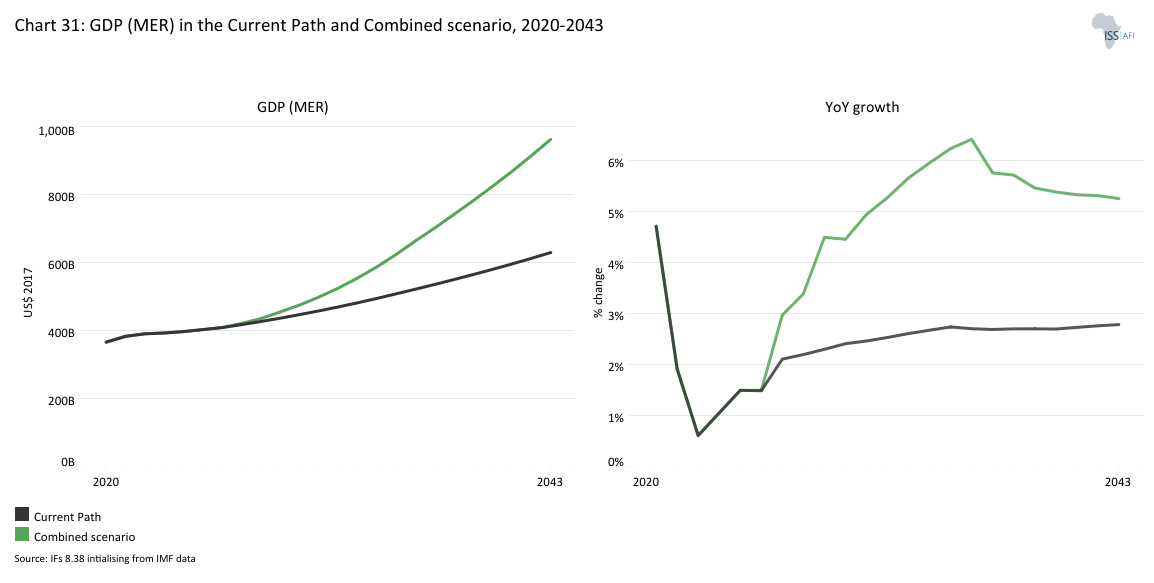

- Economy will grow steadily, with GDP increasing by 60%, from US$392.1 billion in 2023 to US$628.3 billion by 2043. However, this growth is relatively modest compared to other upper-middle-income countries (UMICs), reflecting ongoing structural challenges in the economy.

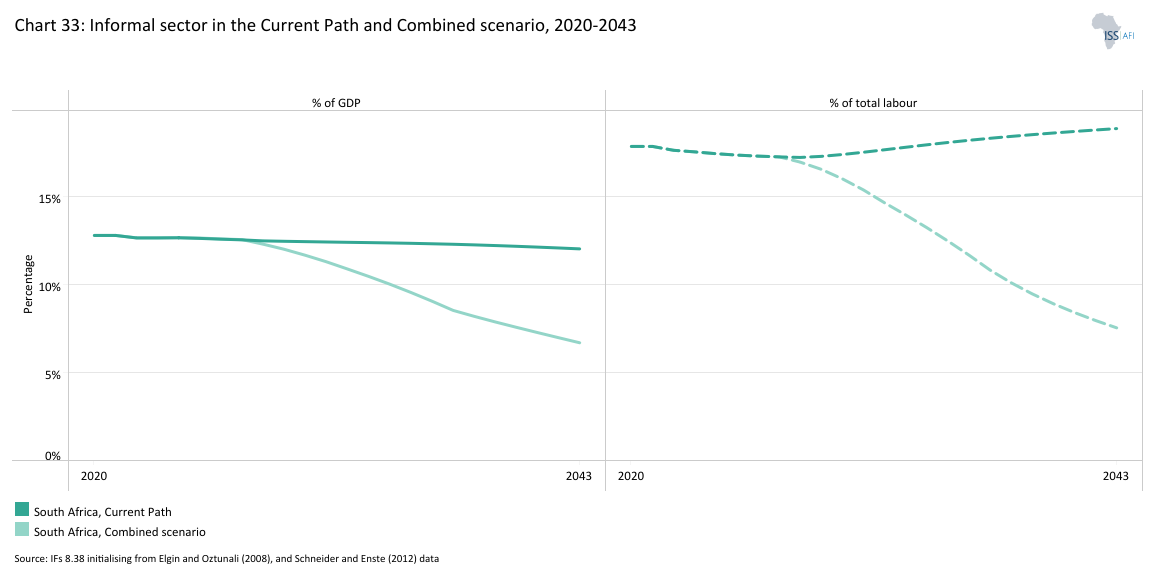

- The informal economy will remain a relatively small part of the overall economy with its contribution to GDP declining slightly from 13% in 2023 to 12% in 2043. Different to most other African countries many South Africans are unemployed and not economically active. The limited size and slow growth of the informal sector constrains economic opportunities for those outside the formal labour market, constraining poverty reduction efforts.

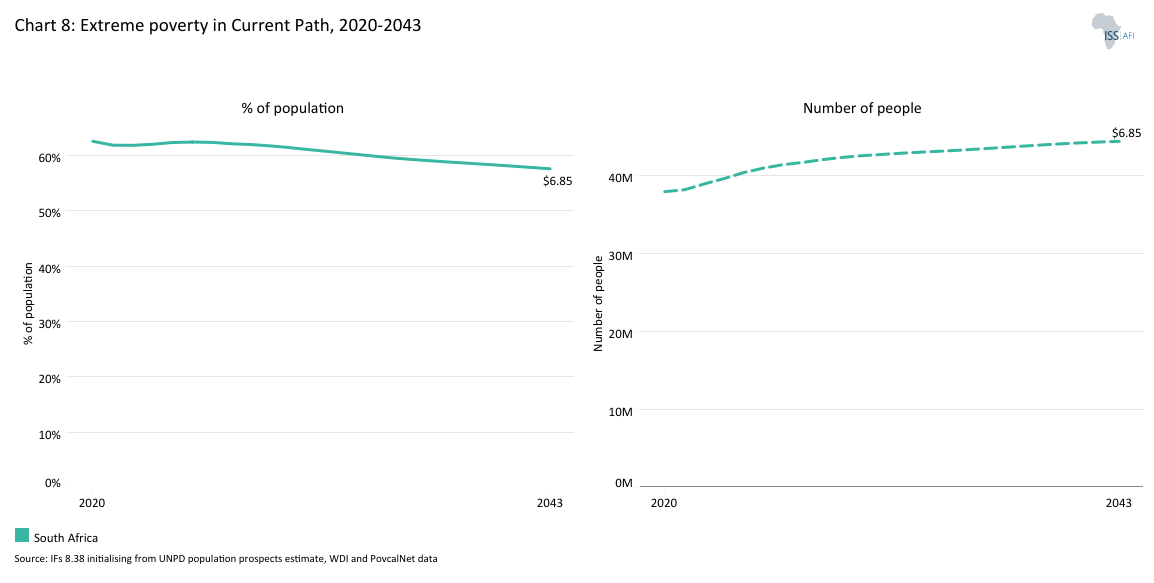

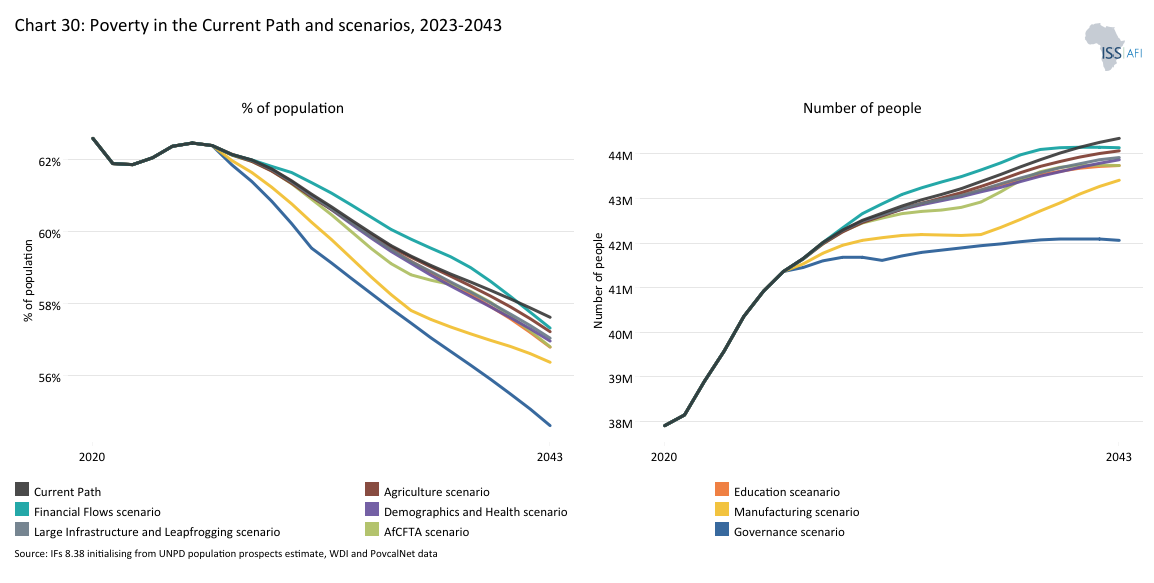

- Poverty levels are anticipated to remain significant. The percentage of people living below the upper-middle-income poverty line of US$6.85 per day will decline modestly from 62% in 2023 to 58% in 2043. Poverty rates are extraordinarily high, exacerbated by persistent inequality and high unemployment.

- Development challenges will persist, including unemployment and underinvestment in critical areas such as healthcare and education. The Current Path underscores the need for effective structural reforms and policy interventions, as outlined in the 2011 National Development Plan (NDP), to promote inclusive growth and improve socio-economic outcomes.

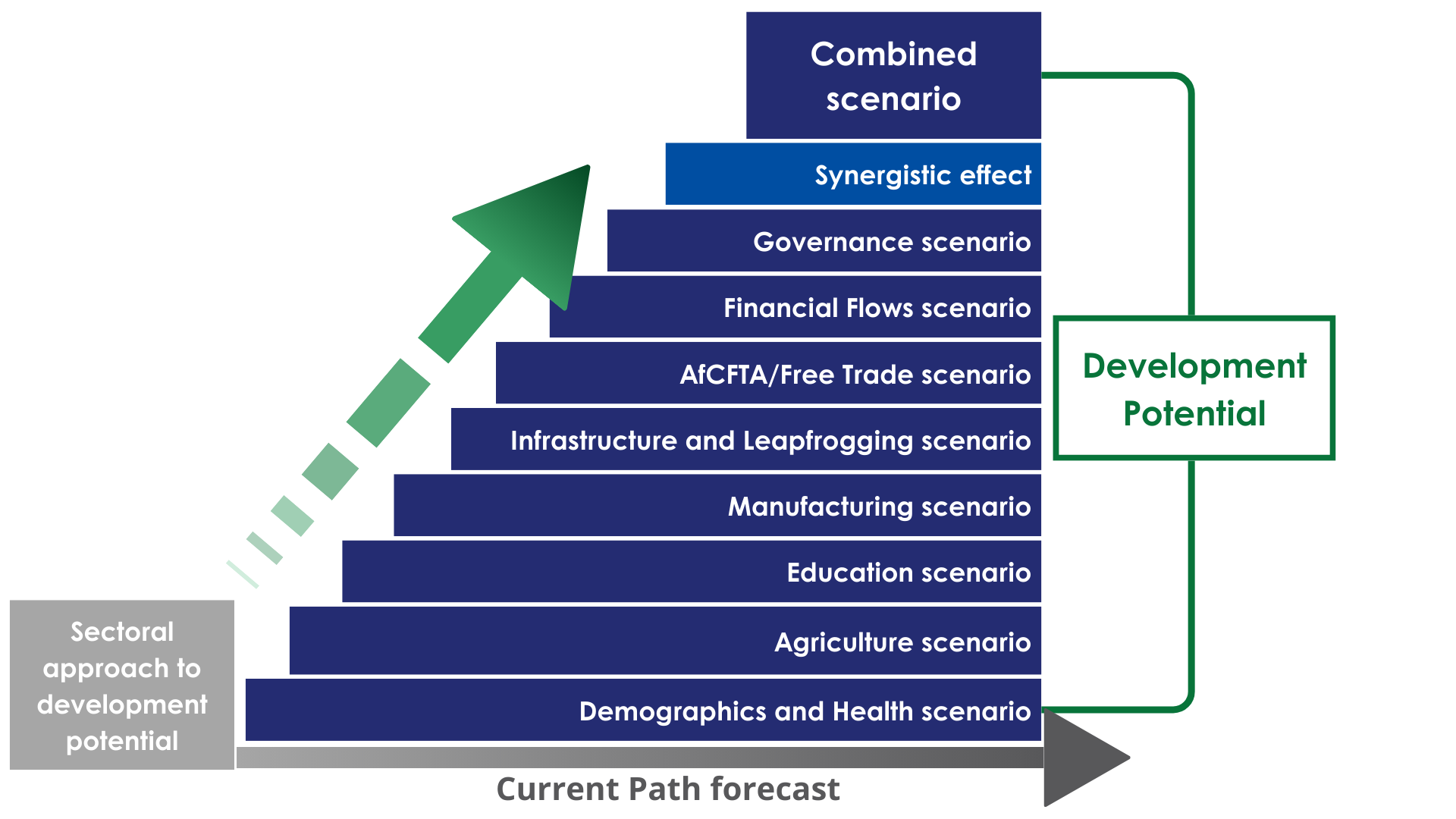

The analysis then compares progress on the Current Path with eight sectoral scenarios: Demographics and Health; Agriculture; Education; Manufacturing; the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA); Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging; Financial Flows; and Governance. Each scenario is benchmarked to present an ambitious but reasonable aspiration in that sector.

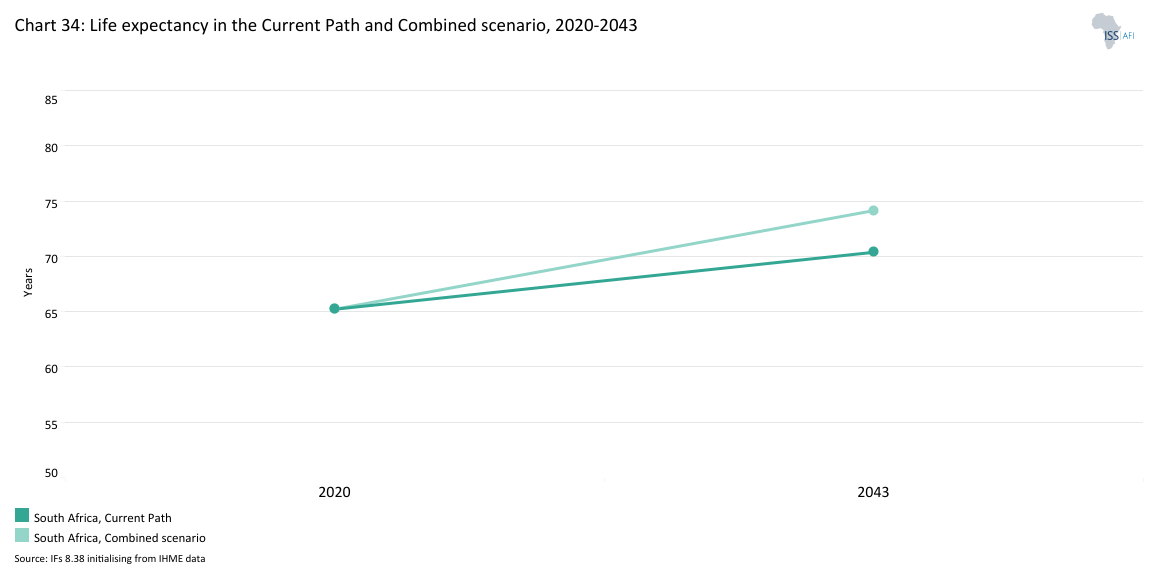

- The Demographics and Health scenario projects significant improvements in health outcomes, with life expectancy increasing to 73 years by 2043, compared to 70.4 years on the Current Path. Infant mortality rates decline from 31.3 per 1 000 live births in 2023 to 21 per 1 000 by 2043, and new treatments mean substantially lower AIDS-related deaths. This scenario highlights the boost in the economic productivity of the working-age population due to better health and reduced disease burden.

- The Agriculture scenario sees average crop yields increase from 5.6 metric tons per hectare in 2023 to 7.2 metric tons per hectare by 2043, compared to the Current Path of 5.5. As a result, crop production will reach 87 million metric tons by 2043, exceeding the projected demand. Targeted investments in the sector boost its contribution to GDP, increase export earnings, reduce import dependence and lift approximately 180 000 additional people out of extreme poverty by 2043 compared to the Current Path.

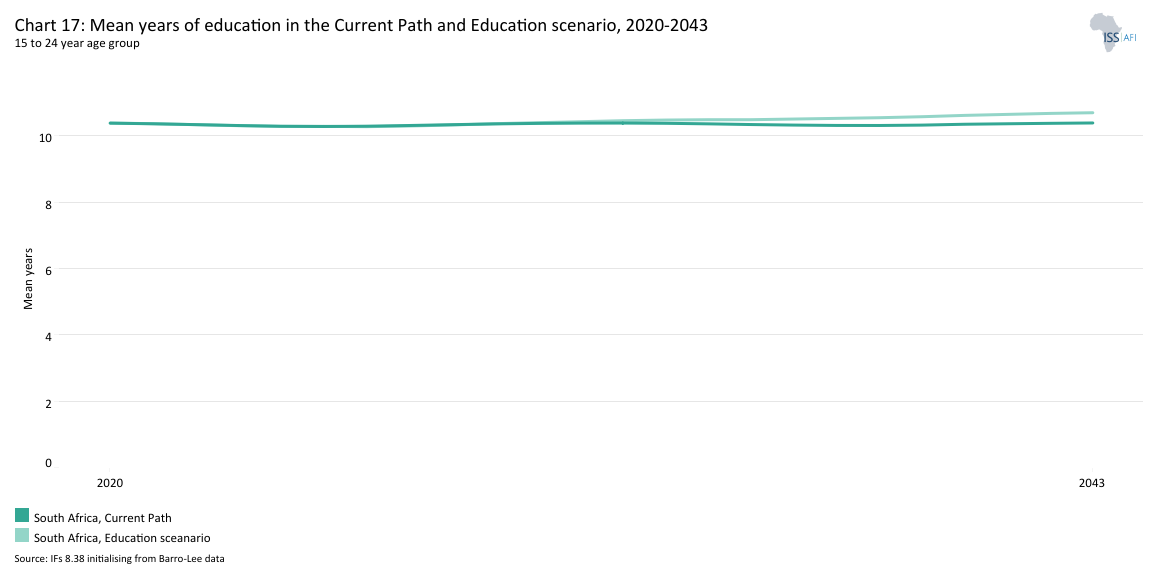

- In the Education scenario, upper-secondary completion rates increase to 83% by 2043, compared to 68% in the Current Path. In 2023, they stood at 62%. Additionally, the scenario includes a 13% quality improvement in primary and a 17% quality improvement in secondary education. Mean years of education among the 14- to 24-year-old age cohort reach 10.7 years by 2043, contributing to a more skilled and knowledgeable workforce.

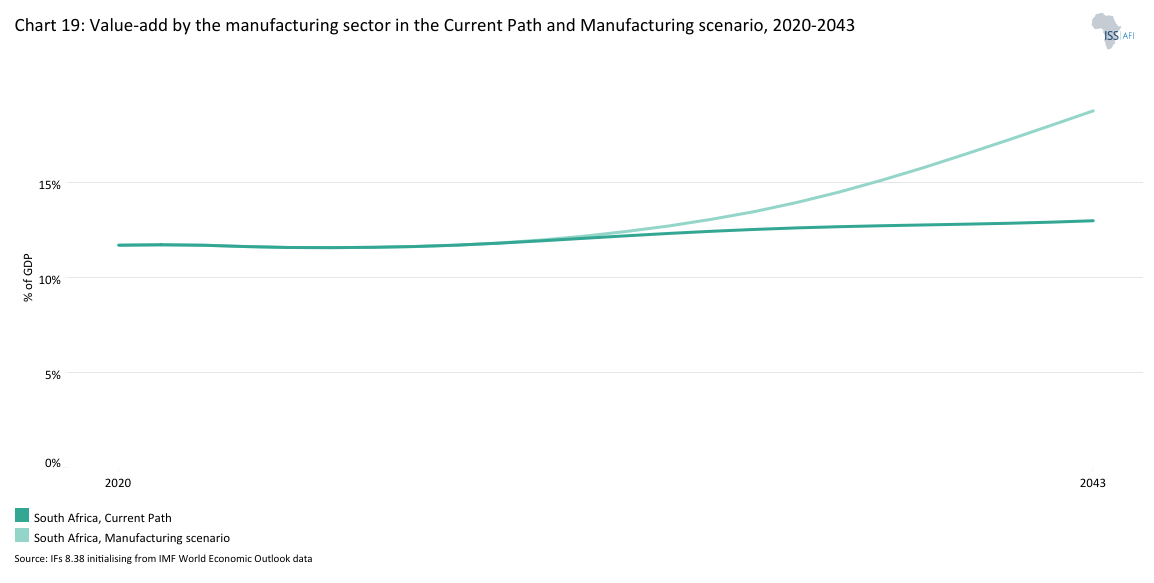

- In the Manufacturing scenario, the contribution of manufacturing to GDP increases from 11.62% (US$46 billion) in 2023 to 18.8% in 2043, equivalent to US$129 billion in 2043. This growth increases the total size of the South African economy by 9.3% to US$687 billion in 2043, instead of US$628 billion.

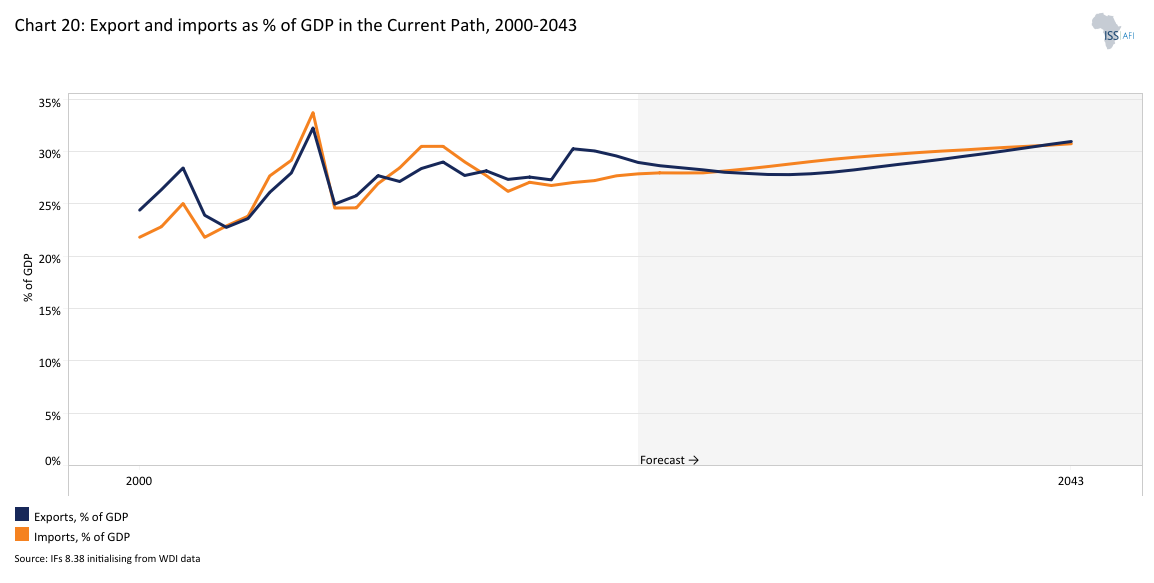

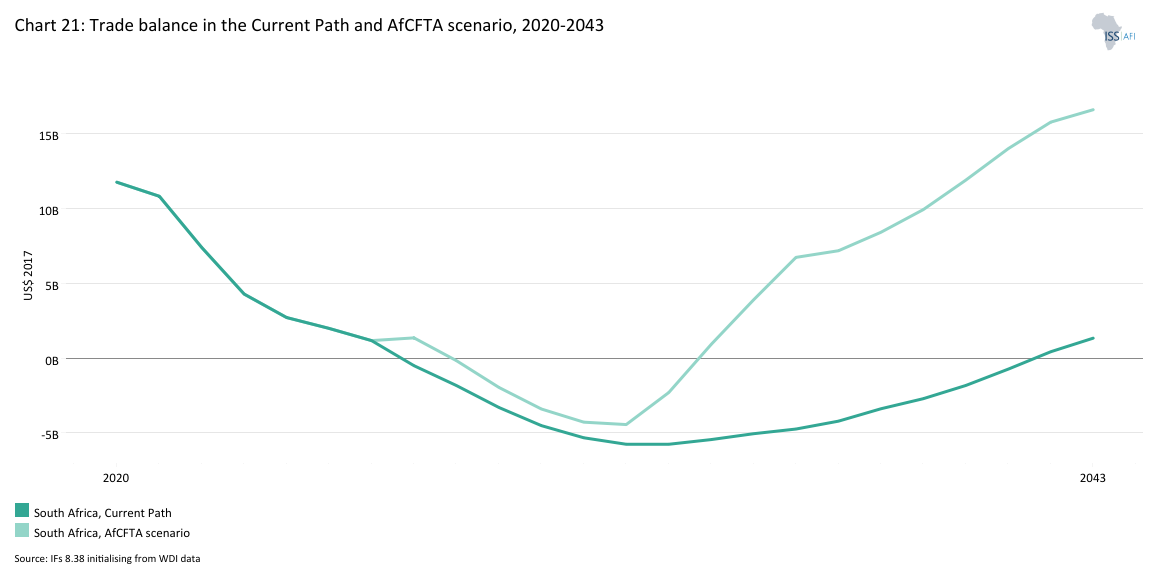

- In the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) scenario, South Africa's total trade (exports plus imports) as a percentage of GDP will increase from 57% in 2023 to 72% by 2043, compared to 62% on the Current Path. South Africa's GDP will be 9% larger by 2043, amounting to an additional US$54 billion compared to the Current Path. GDP per capita will increase to US$15 600 in the AfCFTA scenario, an improvement of almost 6% over the Current Path, highlighting the substantial benefits of enhanced regional and global trade integration.

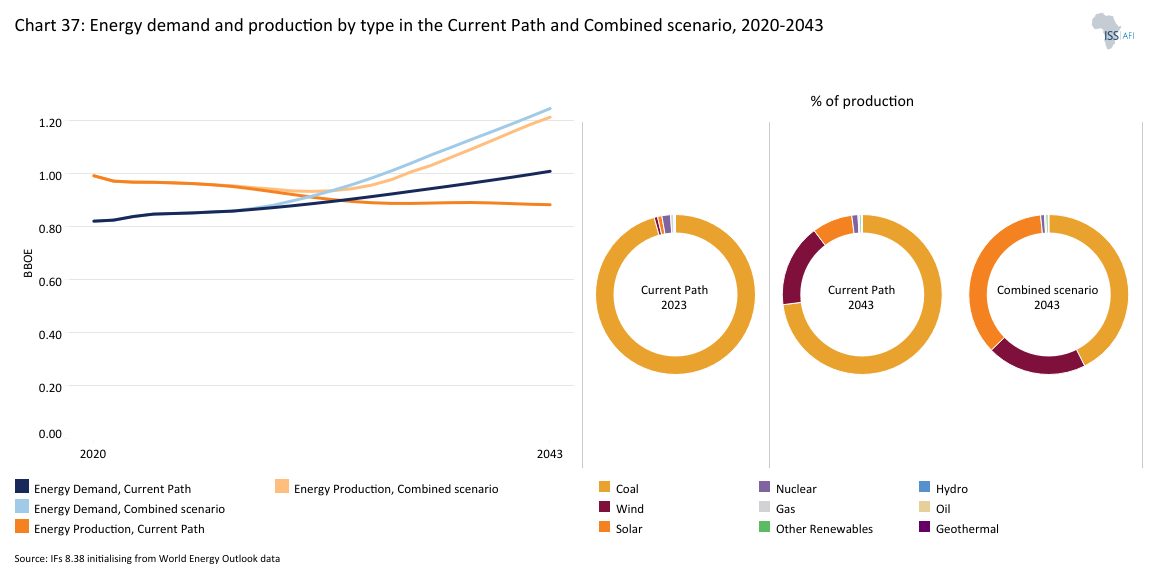

- The Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario forecasts significant increases in infrastructure investment and capacity, leading to an economy that is US$20 billion larger by 2043 compared to the Current Path. Additionally, GDP per capita would be US$320 higher, and an extra 280 000 people would be lifted out of extreme poverty. The scenario boosts fixed broadband subscriptions to 26 per 100 people by 2043, up from the Current Path of 22. These improvements drive economic growth and enhance social and environmental outcomes, including a substantial reduction in carbon emissions through more renewables, solar and wind in particular. This is done on the back of electricity access increasing to near universal levels with reliance on a much more diverse and sustainable energy mix by 2043.

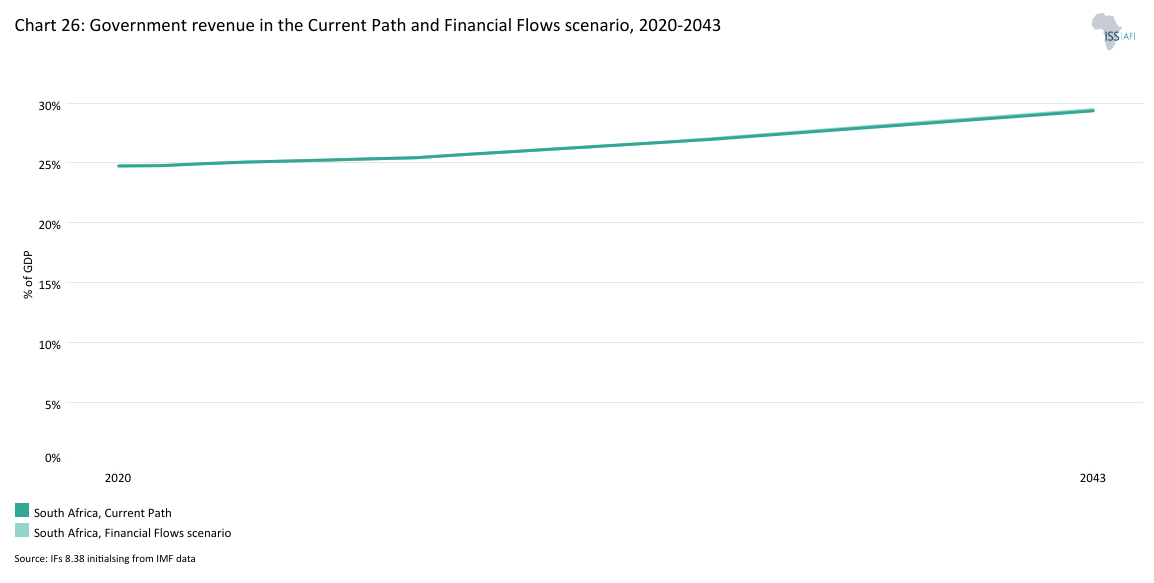

- The Financial Flows scenario envisions a significant rise in FDI inflows, reaching 4.7% of GDP by 2043, compared to 2.2% on the Current Path. This increase would boost South Africa’s FDI stock to US$357 billion, significantly higher than the Current Path of US$203 billion. The scenario will result in substantial economic benefits, including an economy that is US$38.5 billion larger by 2043, and an increase in per capita income by US$610 compared to the Current Path. Achieving these elevated FDI levels would require policy certainty, regulatory improvements and enhanced credit ratings, which would accelerate growth and improve living standards for South Africans.

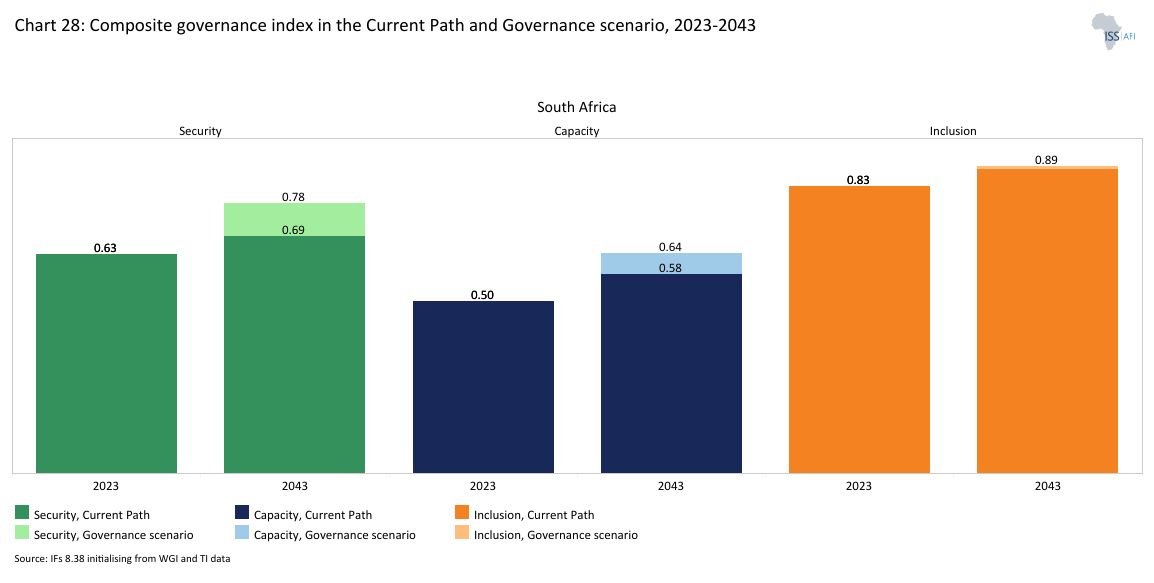

- The Governance scenario will significantly reduce poverty and drive economic growth, positioning South Africa ahead of Namibia and narrowing the gap with Botswana. By tackling security challenges and institutional weaknesses, the scenario boosts investment confidence and economic stability, leading to an expected GDP per capita increase of approximately US$840 above the Current Path. While South Africa already excels in inclusion, targeted reforms in capacity and security will be essential to ensuring long-term development, restoring public trust and unlocking economic potential.

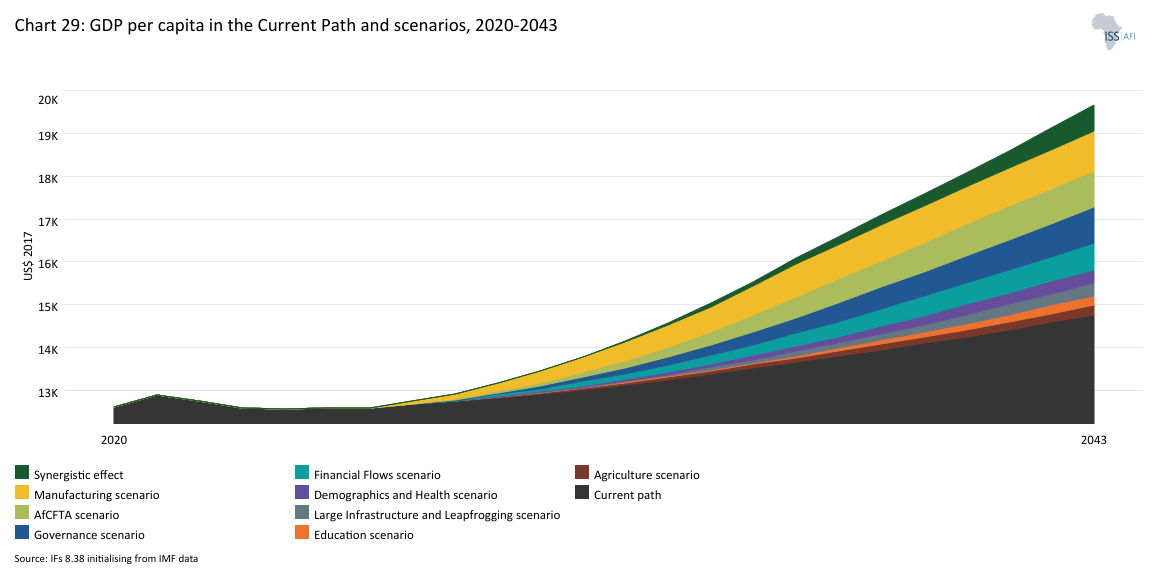

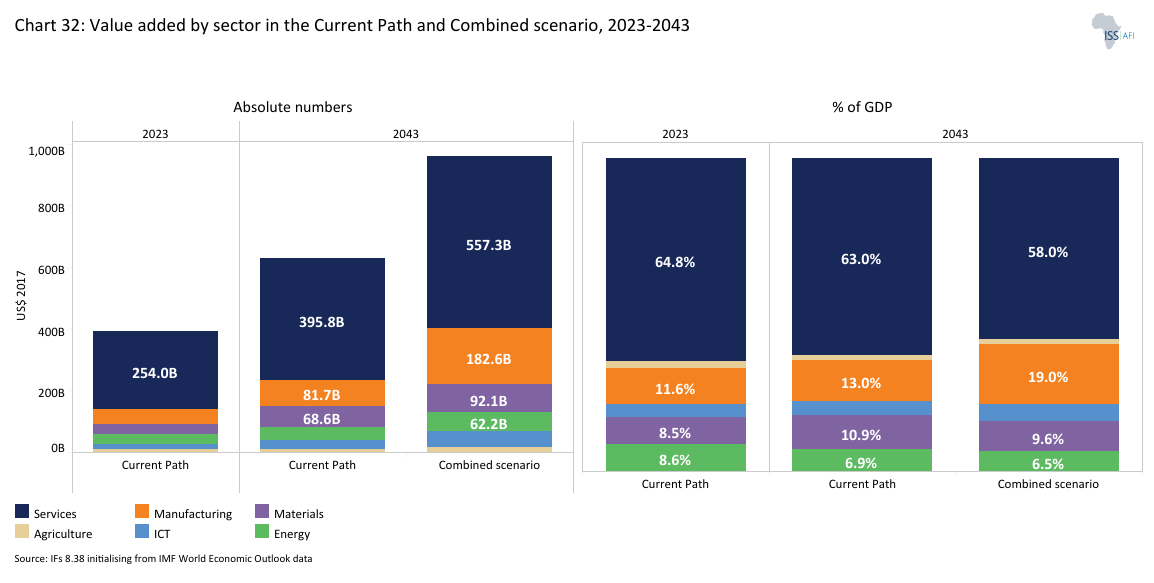

In the fourth section, we compare the impact of each of these eight sectoral scenarios with one another and subsequently with a Combined scenario (the integrated effect of all eight scenarios). In our forecasts, we measure progress on various dimensions such as economic size (in market exchange rates), gross domestic product per capita (in purchasing power parity), extreme poverty, carbon emissions, the changes in the structure of the economy, and selected sectoral dimensions such as progress with mean years of education, life expectancy, the Gini coefficient or reductions in mortality rates. Because we include large increases in welfare transfers in the Governance scenario, it does best in extreme poverty reduction, followed by the Manufacturing and Education scenarios. The Manufacturing scenario also delivers the highest GDP per capita by 2043, followed by the AfCFTA and Governance scenarios.

The Combined scenario forecasts:

- a substantial 33% increase in GDP per capita above the Current Path by 2043. This equates to an additional US$4 920 per person, indicating a more prosperous economic outlook for most South Africans. As a result, GDP per capita will recover to its 2013 peak level by 2031, eight years earlier than on the Current Path. This reflects a more rapid economic recovery following years of stagnation and decline.

- that among the sectoral scenarios, the Manufacturing scenario shows the largest impact on GDP per capita with a 6.3% increase (US$930) above the Current Path by 2043. This is followed by gains in the AfCFTA (5.8%), Governance (5.7%) and Financial Flows (4.1%) scenarios, highlighting the importance of diverse sectoral interventions for broad-based economic development.

- a solid reduction in the poverty rate (using US$6.85) to 50% by 2043, down from 62% in 2023. This represents a meaningful decrease of 6.1 million fewer poor people compared to the Current Path, still leaving South Africa with a large poverty burden.

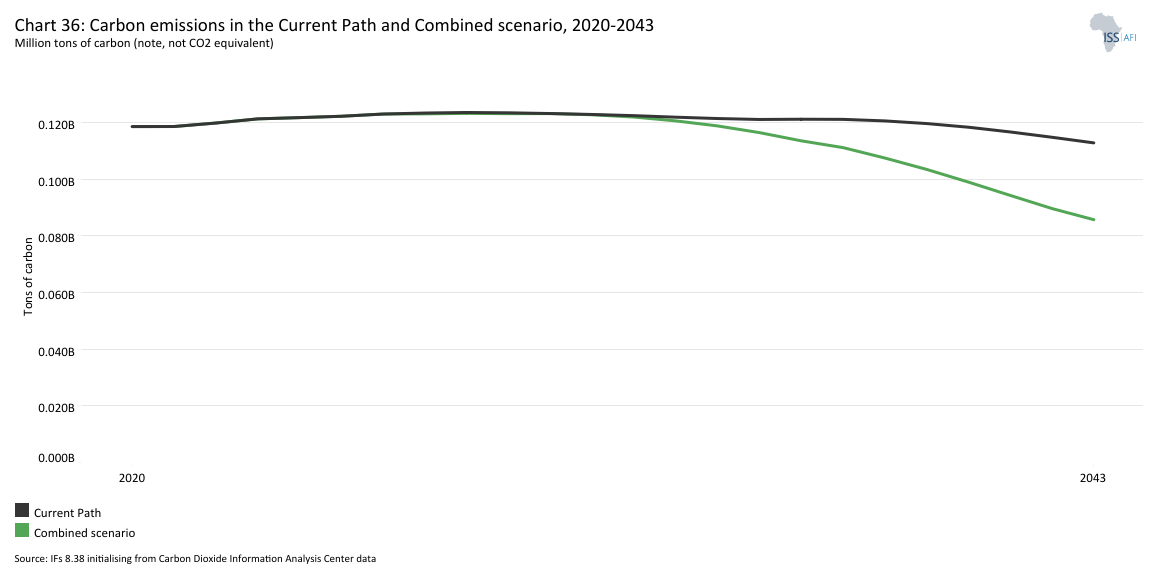

- that the steady replacement of coal by renewables (reflected in the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario) will rapidly reduce South Africa’s carbon emissions such that the emissions in the Combined scenario in 2043 will be 37% below the Current Path, in spite of the fact that the economy will be 53% larger.

We end this page with a summarising conclusion offering key recommendations for decision-making. To achieve sustainable growth and reduce inequality, South Africa must focus on competent leadership, evidence-based policies and fostering a culture of accountability and inclusivity. This requires a shift towards an export-led growth path and significant investments in human capital, infrastructure and green technologies, which are supported by both public and private sectors.

All charts for South Africa

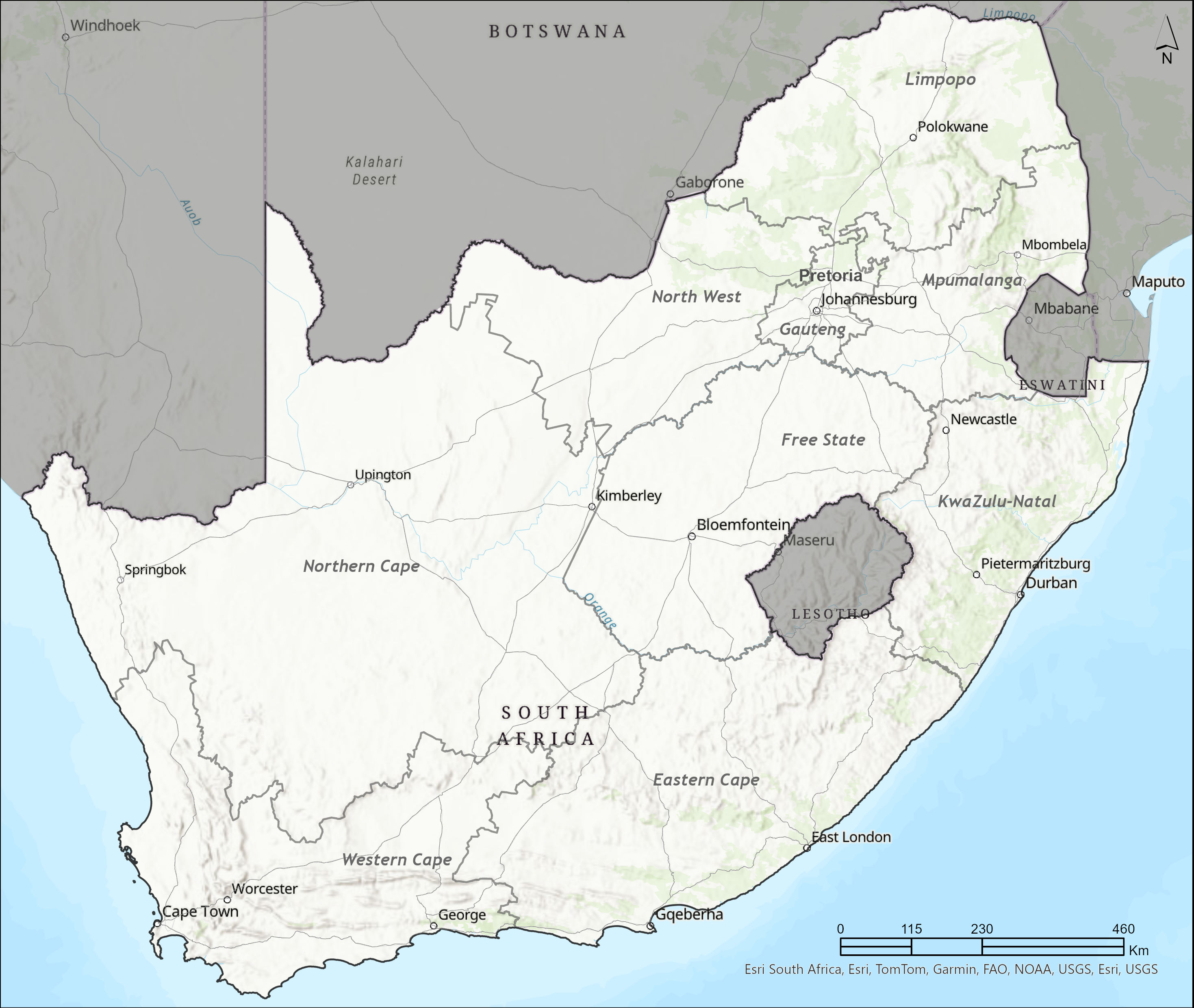

- Chart 1: Political map of South Africa

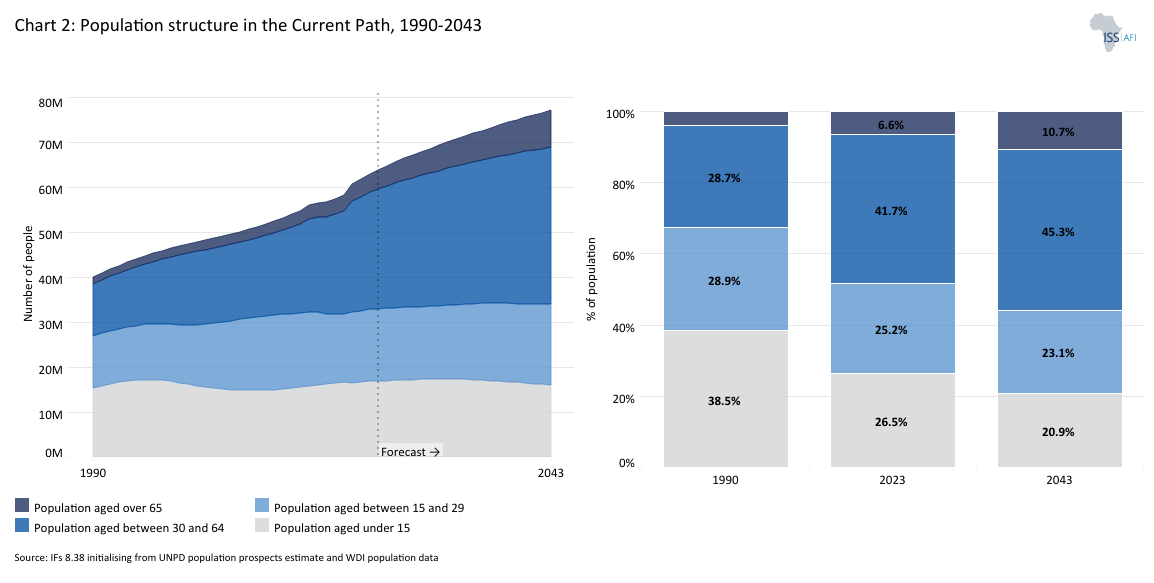

- Chart 2: Population structure in the Current Path, 1990–2043

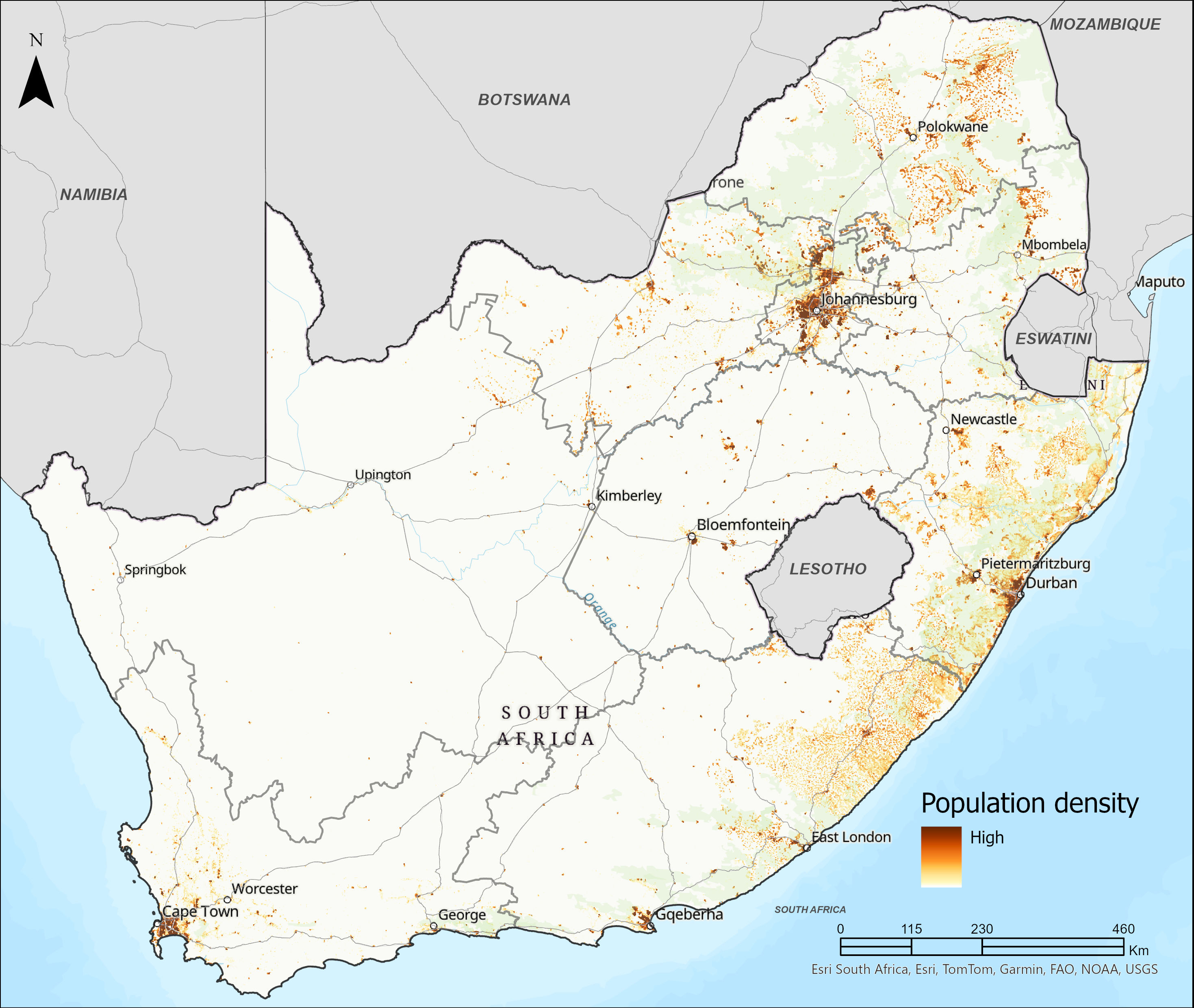

- Chart 3: Population distribution map, 2023

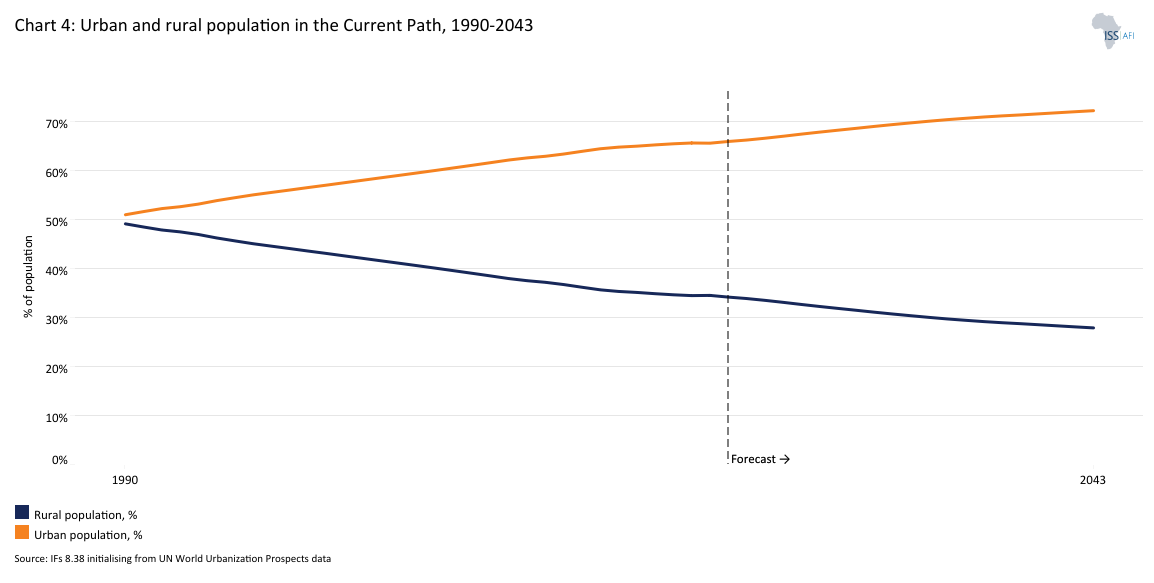

- Chart 4: Urban and rural population in the Current Path, 1990-2043

- Chart 5: GDP (MER) and growth in the Current Path, 1990-2043

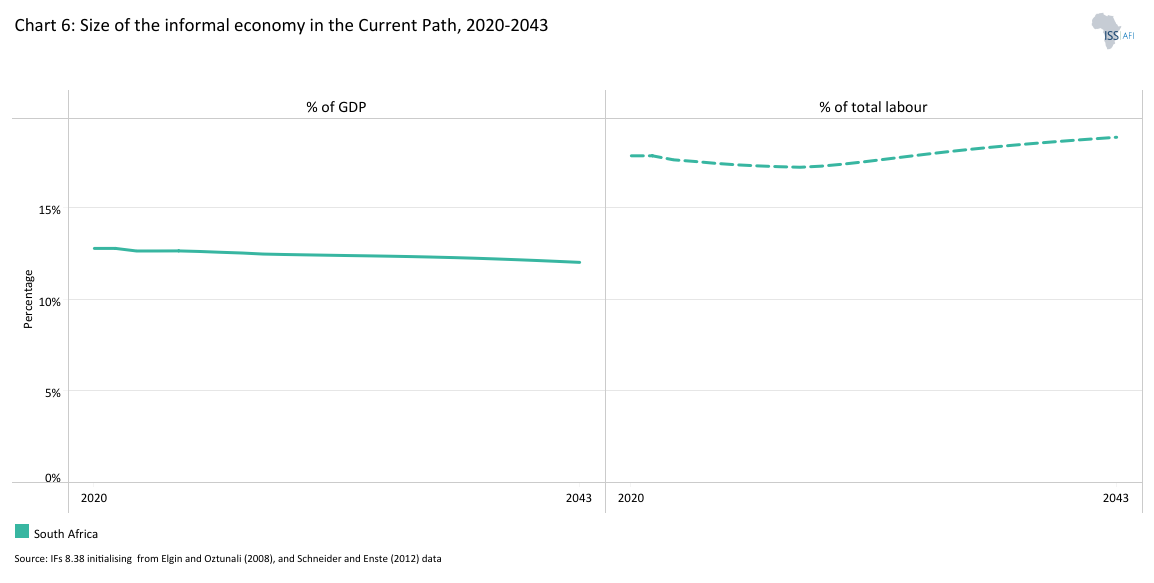

- Chart 6: Size of the informal economy in the Current Path, 2019-2043

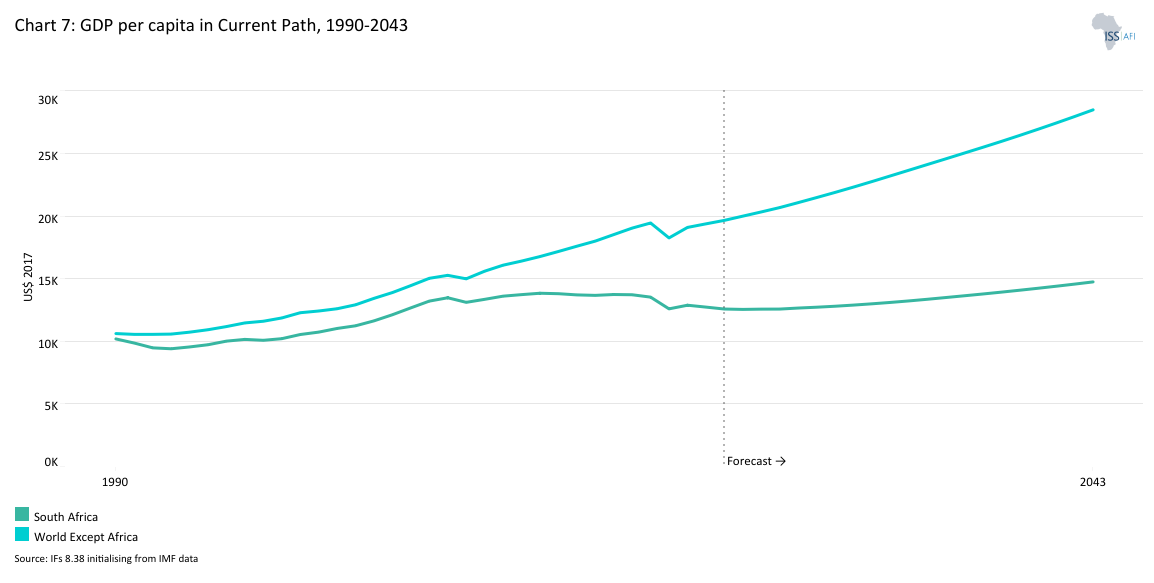

- Chart 7: GDP per capita in Current Path, 1990-2043 compared to global income group

- Chart 8: Poverty in Current Path, 2019-2043

- Chart 9: National Development Plan of South Africa

- Chart 10: Relationship between Current Path and scenarios

- Chart 11: Mortality distribution in Current Path, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 12: Infant mortality rate in Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 2019-2043

- Chart 13: Demographic dividend in Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 2019-2043

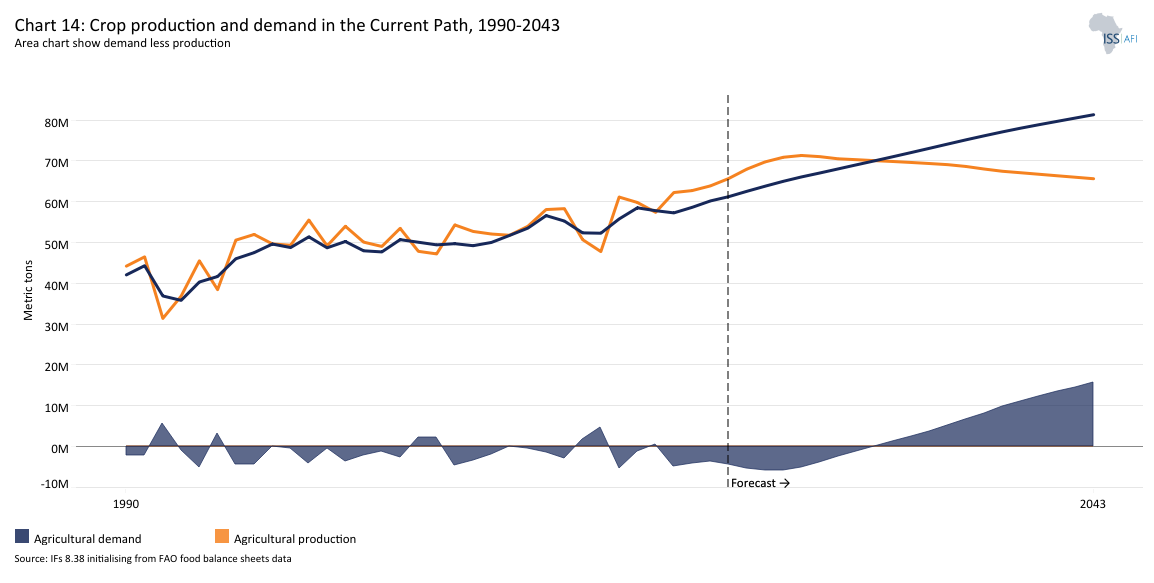

- Chart 14: Crop production and demand in Current Path, 1990-2043

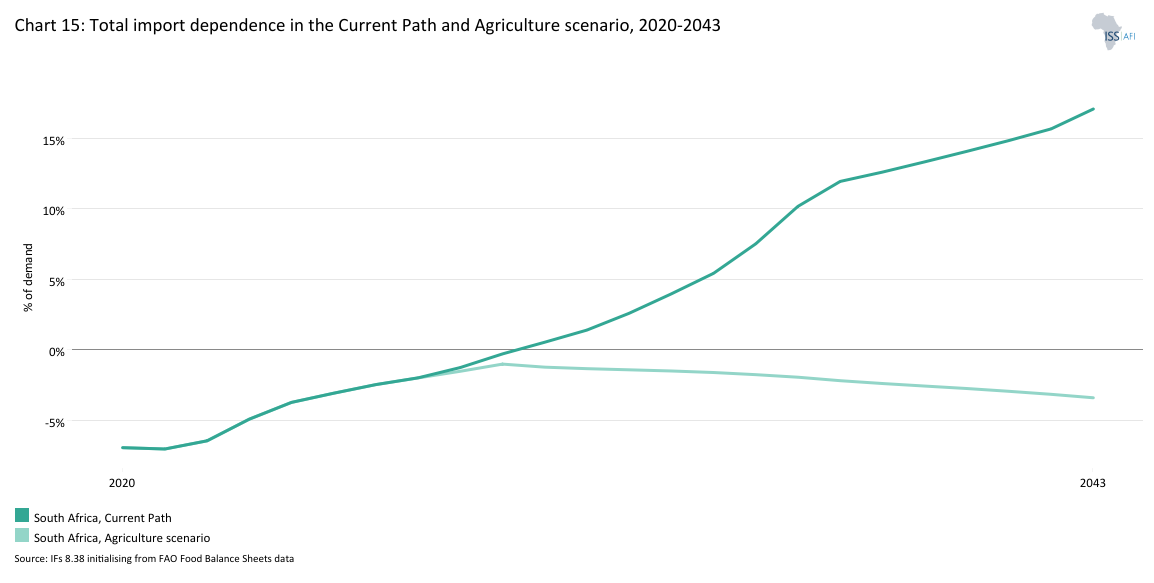

- Chart 15: Import dependence in Current Path and Agriculture scenario, 2019-2043

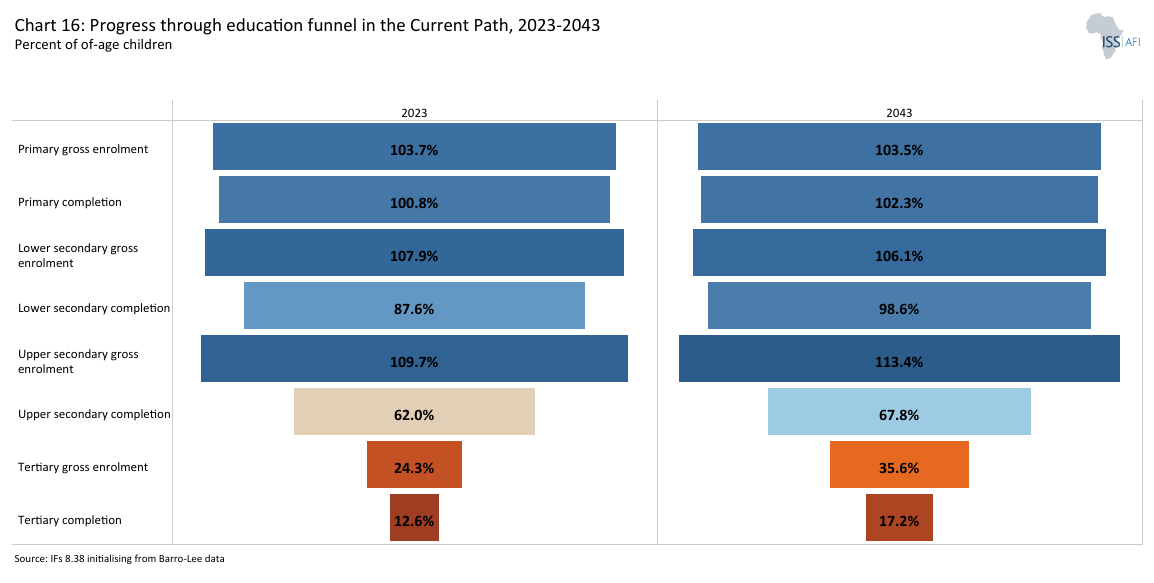

- Chart 16: Progress through education funnel in Current Path, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 17: Mean years of education in Current Path and Education scenario, 2019-2043

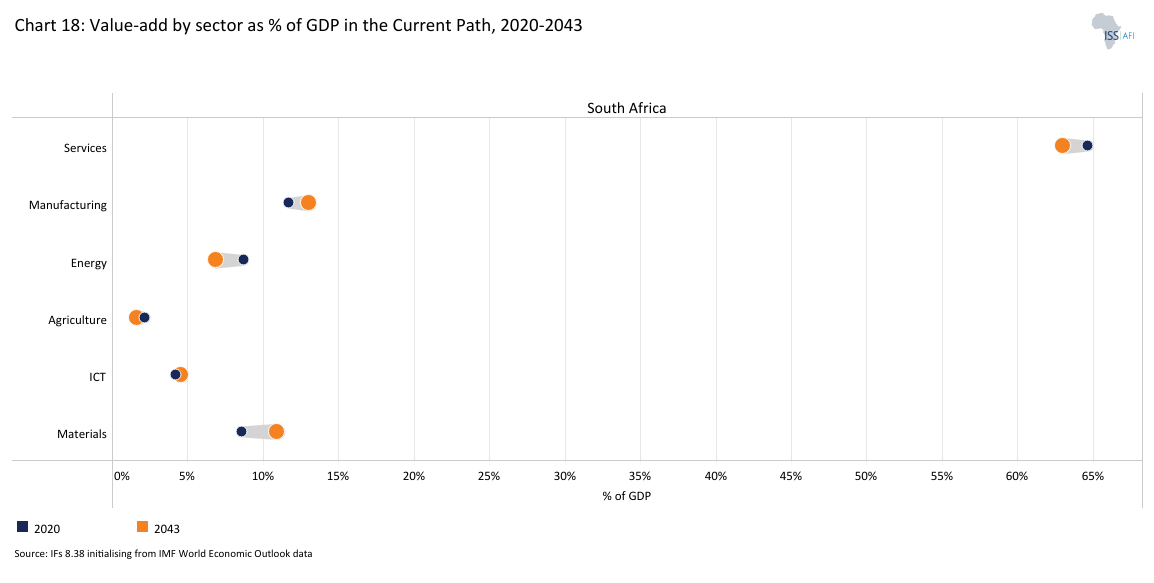

- Chart 18: Value-add by sector as % of GDP in Current Path, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 19: Value-add by the manufacturing sector in Current Path and Manufacturing scenario, 2019-2043

- Chart 20: Exports and imports as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2000-2043

- Chart 21: Trade balance in Current Path and AfCFTA scenario, 2019-2043

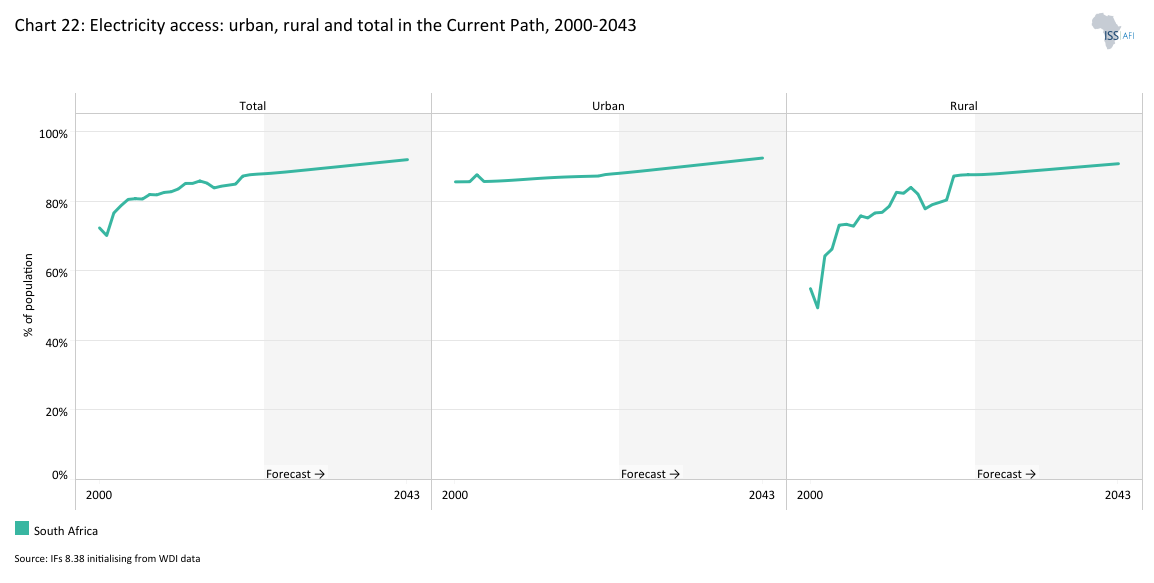

- Chart 22: Electricity access: urban, rural and total in Current Path, 2000-2043

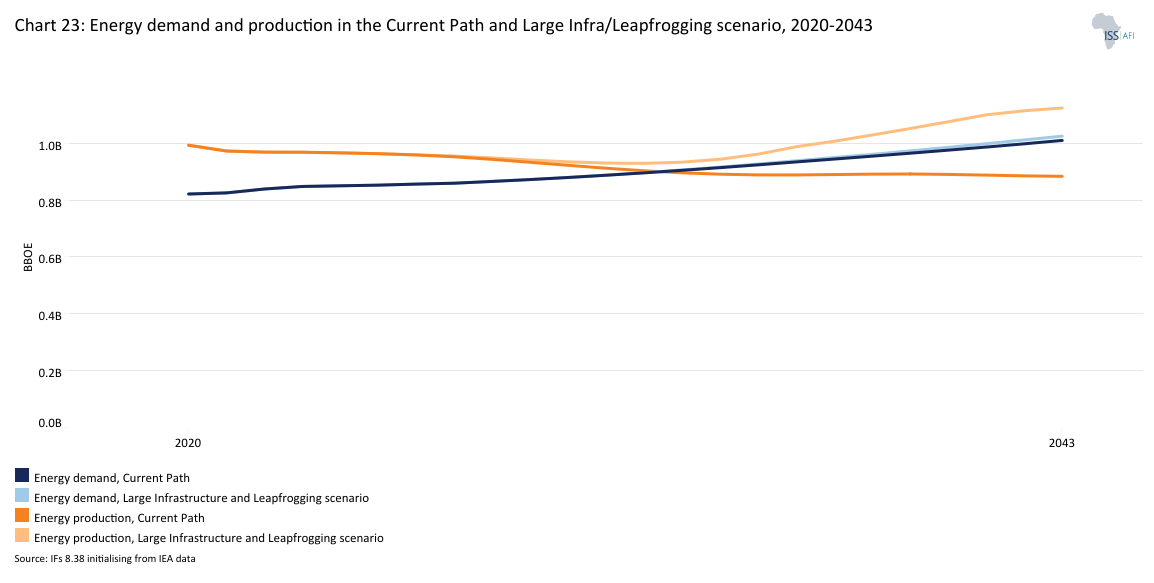

- Chart 23: Energy Demand and production in Current Path and Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

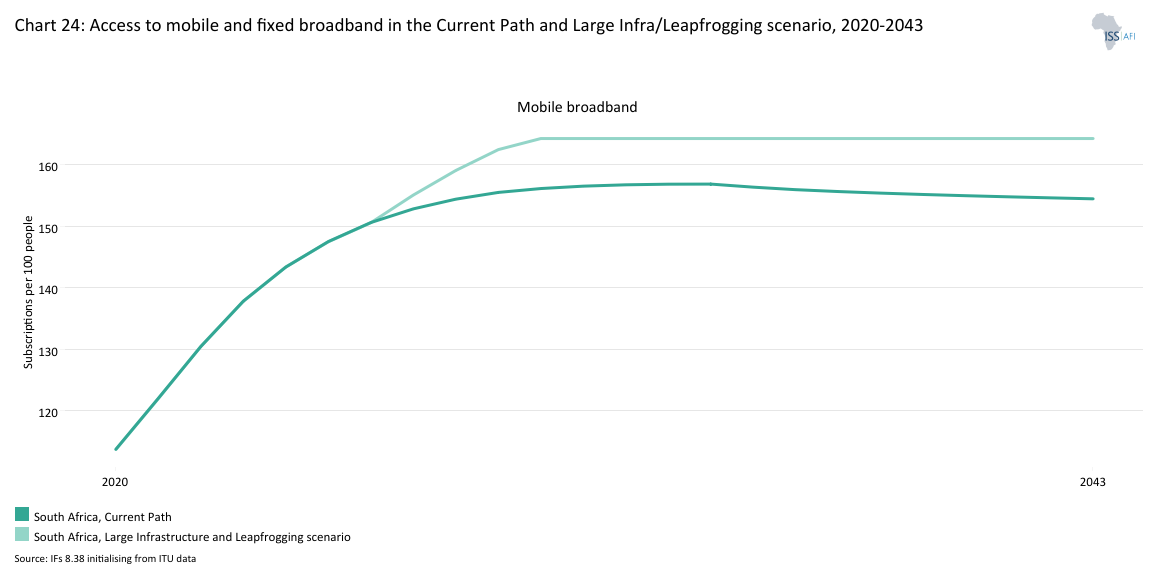

- Chart 24: Access to mobile and fixed broadband in Current Path and Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2019-2043

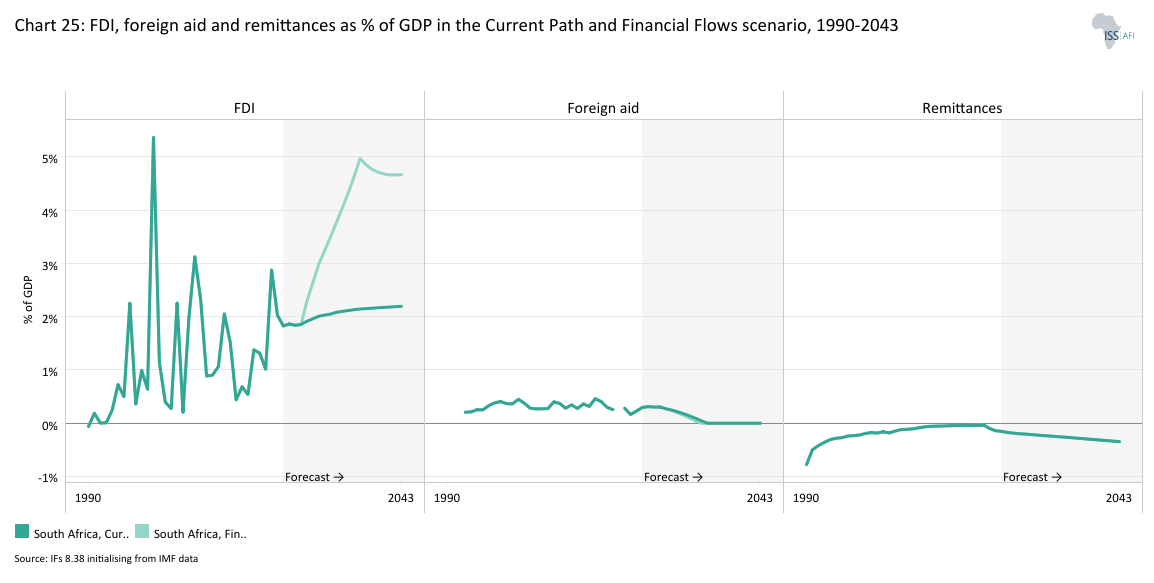

- Chart 25: FDI, foreign aid and remittances as % of GDP in Current Path and Financial Flows scenario, 1990-2043

- Chart 26: Government revenue in Current Path and Financial Flows scenario, 2019-2043

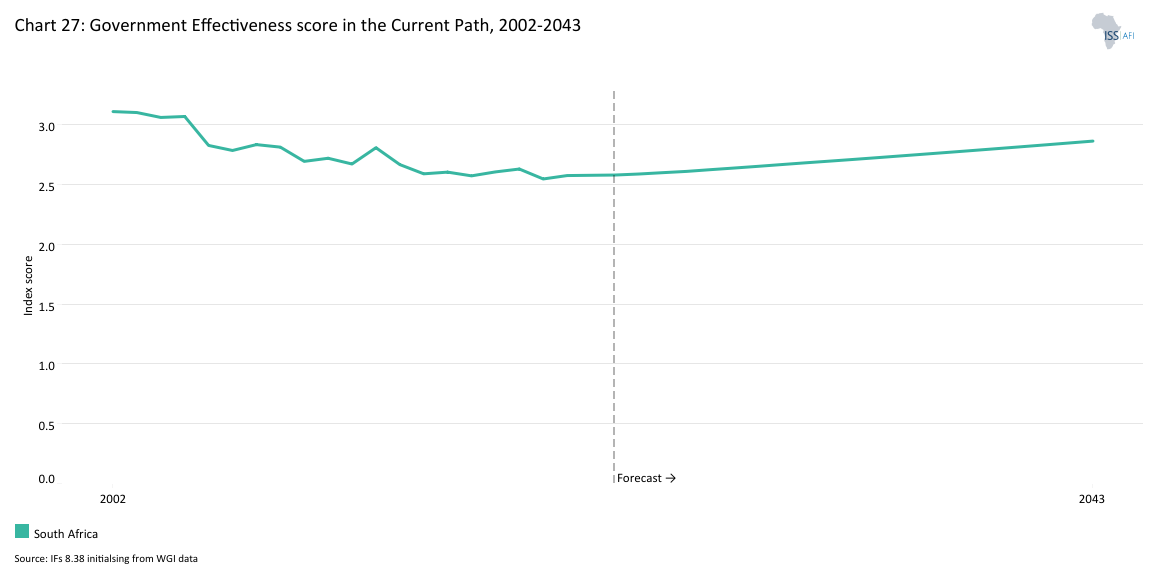

- Chart 27: Government effectiveness score in the Current Path, 2002-2043

- Chart 28: Composite governance index in Current Path and Governance scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 29: GDP per capita in Current Path and all scenarios, 2019-2043

- Chart 30: Poverty in Current Path and all scenarios, 2019-2043

- Chart 31: GDP (MER) in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019-2043

- Chart 32: Value added by sector in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 33: Informal sector in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019-2043

- Chart 34: Life expectancy in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

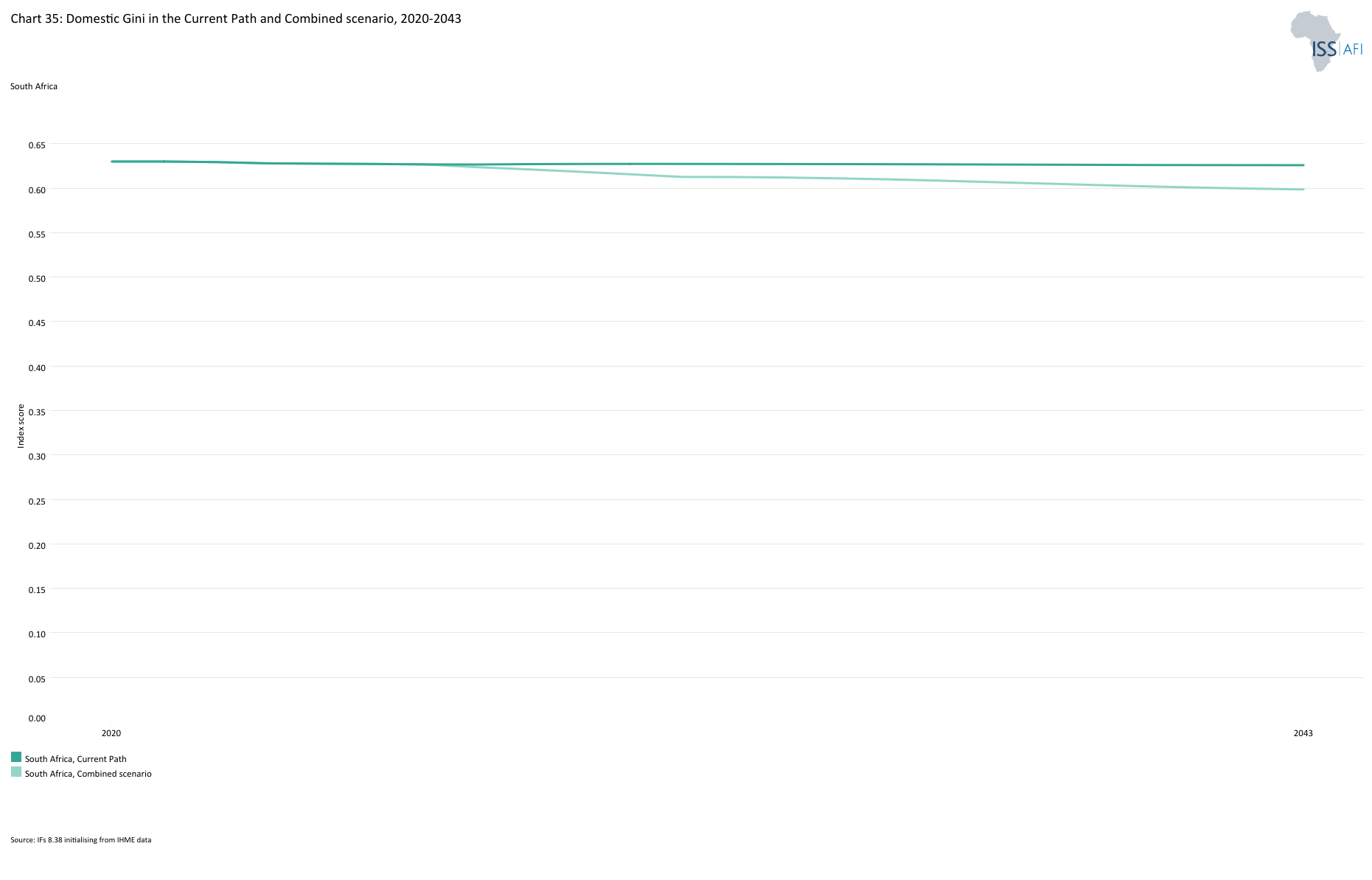

- Chart 35: Domestic Gini in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019-2043

- Chart 36: Carbon emissions in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019-2043

- Chart 37: Energy demand and production by type in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019-2043

- Chart 38: Recommendations

Chart 1 is a political map of South Africa.

Located at the southernmost tip of Africa, the Republic of South Africa is one of eight upper-middle-income countries (UMICs) on the continent. It is a member of the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and is situated in the subtropical zone of the southern hemisphere. Its vast coastline stretches from the tropical border of Mozambique in the warm Indian Ocean, around Africa’s most southern tip and to the border of Namibia’s cold Atlantic Ocean. The country’s geographical location and complex topography mean that South Africa is subject to a range of climatic conditions. Annual rainfall is highly variable, following a declining pattern from the wet and humid eastern coast to the arid western coast. South Africa shares borders with Namibia (which it previously administered), Botswana and Zimbabwe to the north, Mozambique and Eswatini to the east, and completely surrounds the independent Kingdom of Lesotho.

South Africa has nine provinces. The economic heartland, the province of Gauteng, comprises the commercial hub of Johannesburg and the administrative capital, Tshwane (formerly Pretoria). The legislature, comprising a National Assembly and a National Council of Provinces, is situated in Cape Town, in the Western Cape province. Although the smallest province geographically, Gauteng has the largest population, with more than 16 million people, followed by KwaZulu-Natal on the east coast, with almost 13 million inhabitants. The Western Cape, Eastern Cape and Limpopo have between 6 and 8 million people each. Mpumalanga province has 5.3 million people, North West province has 3.8 million. The Free State and Northern Cape provinces have the smallest populations at 3 and 1.3 million, respectively.

Formerly the Union of South Africa, the country became an independent republic in 1961 and was, from 1948 to 1990, ruled by the whites-only National Party, which pursued policies of racial subjugation and separation known as apartheid. As the apartheid crisis deepened, South Africa experienced negative per capita economic growth over the two decades from 1973 to 1993, to the extent that 1993 incomes were back to those in 1970. Capital investment decreased, and ever-larger portions of the national budget had to be allocated to fund recurring expenditures. Infrastructure decayed, and efficiencies declined.

Internal revolt against apartheid saw successive waves of unrest that, together with global pressure, led to the unbanning of several political parties, including the African National Congress (ANC), and the release of Nelson Mandela from prison in 1990. These events followed the collapse of the Soviet Union and several years of armed conflict in the neighbourhood, during which apartheid South Africa was increasingly isolated from the international community and under various types of sporting, arms and financial sanctions. When it assumed power in 1994, following several years of negotiation towards power-sharing, the ANC inherited a country with bare coffers but high expectations from its majority black support base, who believed that political change would rapidly redress the neglect they had suffered over generations.

The constitutional negotiations, known as the Convention for a Democratic South Africa or CODESA, resulted in a liberal constitution with a clear separation of powers and an entrenched bill of rights. The election of Nelson Mandela as president in 1994 set in motion a comprehensive, if inconclusive, process of social, economic and political re-engineering. Within the first three years, the democratic government introduced new labour legislation that modernised the South African labour market and protected worker rights. Democracy also meant the abolishment of the efforts to establish independent homelands for various black ethnic groups (the so-called Bantustans), although traditional chiefs were left in place. The fragmented, race-based education departments were merged into a non-racial education system, and separate administrations were brought together. The previous four provinces were divided into nine, each with local, provincial and national elected representatives. What had been a centralised, racially determined state with a limited franchise adopted a universal franchise and a semi-federal model, extending political, economic, and social rights to all citizens through a progressive Bill of Rights. South Africa today has a free media, an independent judiciary and an active civil society.

A wide-ranging process of land restitution followed in the wake of an inquiry into the excesses of apartheid (the Truth and Reconciliation Commission). Concerted efforts were also made to alleviate extreme poverty and advance the interests of the majority black population.

In the years following its transition to democracy, improved foreign perceptions of South Africa's attractiveness for doing business led to significant foreign financial inflows. Large segments of the South African economy were opened up to international competition, and labour productivity increased from 1995. For the next 15 years, until 2008, the country experienced growth and improved income levels, yet at a much slower pace than it could have, due to policies that prioritised addressing the socio-economic imbalance created by apartheid, but effectively constrained growth.

The opening up of the South African economy also coincided with the explosive, export-driven growth of China and other countries reaching African shores. Not accustomed to international competition and having decided to remove most of its previous tariffs and other protections, South Africa experienced deindustrialisation, such that, by 2024, the World Bank wrote about a 15-year loss of economic growth momentum and underperformance compared to other middle-income countries.

Despite its challenges, South Africa competes with Nigeria for the largest economy in Africa and has a relatively high average income per capita compared to most other countries in the region, although it is lower than that of Seychelles, Mauritius, Botswana, and Equatorial Guinea. The South African economy is also more globally interconnected than most other African countries, reflected in its status as Africa’s largest trading nation (by value).

However, colonialism, apartheid and ongoing poor governance and corruption have resulted in extreme levels of inequality, with high rates of poverty, unemployment, crime and violence, exacerbated by low productivity and a high-wage economy.

Unlike many other countries with similar challenges, South Africa has a relatively small informal economy (which contributes to its high unemployment and inequality rates), and an increasing portion of its population survives on social grants from the government. It has a thriving tourist industry, but declines in the contribution from the mining sector and competition from China have contributed to a steady decline in industrialisation. The country has a sophisticated private sector, highly developed financial markets, and substantial natural assets. However, savings rates as a percentage of GDP are low, approximately eight percentage points below the average for upper-middle-income countries (UMICs) globally. Its small commercial agricultural sector is efficient, and South Africa is one of a handful of food-secure African countries.

Among the labour-intensive sectors, mining was historically the most important (note that in our modelling, mining is part of the materials sector). In 1980, mining accounted for approximately 21% of the GDP. It peaked at providing 760 000 jobs a few years later, mainly on the back of South Africa’s enormous gold mining industry, which was its primary mining product. By 2023, that number had declined to 6.2% of GDP, and employment stood at 477 000 persons. Mining is particularly important in the poverty-stricken North West, Limpopo, Mpumalanga and the Northern Cape provinces, but has declined and has given rise to a large criminal and illegal artisanal sector, so-called zama zamas. The remaining mining sector is export-oriented, largely due to the limited domestic demand for most commodities, and it still holds significant potential for the future. South Africa has, among other resources, the world's largest known reserves of platinum group metals (PGMs), chrome ore, and manganese ore, as well as the second-largest reserves of zirconium, vanadium, and titanium.

Mining is tightly woven into the fabric of South Africa’s history and provided the stepping stone upon which its industrial development occurred. Still, it has deteriorated in recent years due to government inefficiencies that have hindered exploration, resulting in slow progress in rolling out a new mining cadastre, now scheduled for completion in mid-2025. As a result, there is no pipeline for new projects (although some progress has been made with the establishment of an exploration fund), and the sector is subject to numerous and expensive social responsibility obligations, as well as the effects of organised crime syndicates. It was therefore unsurprising that, in 2023, Canada’s Fraser Institute once again ranked South Africa near the bottom of its global mining survey, at number 57 (out of 62 jurisdictions assessed).

Under the administration of former President Jacob Zuma, from May 2009 to early 2018, South Africa experienced steadily declining levels of investor confidence, state capture, and increased government inefficiencies, accompanied by a decline in average incomes. Zuma was succeeded by Cyril Ramaphosa, who then had to contend with the COVID-19 global pandemic, slower economic growth, and the divisions within the ruling ANC, which had become increasingly corrupt. Prospects are improving, however. Crippling electricity shortages began to ease in 2024, after more than a decade of hobbled growth, during which the government failed to respond to repeated warnings of imminent shortages. However, the shortages and subsequent high prices remained a constraint on economic growth as the country belatedly scrambled to add additional capacity to the grid. Hard work will be required to avoid a similar situation related to water shortages, despite repeated warnings of an impending crisis over several years. The demand for water in both Gauteng and eThekwini has grown rapidly, primarily due to population growth and inadequate maintenance, resulting in significant non-revenue water losses.

The ANC, which has won every election since the country’s first democratic elections in 1994, saw its support plummet to 40% in May 2024 as evidence of corruption, inaction and poor policy that overwhelmed the country, significantly abetted by Jacob Zuma, whose new party, uMkonto we Sizwe (MK), drew significant support from the ANC. Previous elections have seen a steady decline in voter turnout, and politics is increasingly fragmented. In addition to the Western Cape, which has been governed by the Democratic Alliance since 2009, the ANC lost its majority in Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, and narrowly in the Northern Cape. The subsequent governing alliance (formally termed a Government of National Unity, although not all parties are members) has given hope that the country could unlock improved service delivery, reduce rampant corruption and reduce crime.

Chart 2 presents the Current Path of the population structure from 1990 to 2043.

Population dynamics play a crucial role in economic development, and South Africa has considerable potential, given its favourable ratio of working-age population to dependents, which suggests the potential for a demographic dividend. However, its population is in poor health, primarily due to the effects of HIV/AIDS and Tuberculosis (TB), which is closely linked with HIV/AIDS, compounded by various other factors examined below as part of the Demographics and Health scenario. Education quality is generally low (see the Education scenario below).

South Africa is one of the few countries in Africa that conducts a regular population census. However, the most recent Census 2022 was conducted digitally during the COVID-19 pandemic, and since the results differ from other projections, they require careful consideration. Therefore, this analysis does not fully incorporate these census results.

Given its history, race remains a significant factor in South Africa. Black Africans make up the majority of the population at 81%, followed by the coloured population at 9%. On the back of low fertility rates and significant emigration, the white population percentage declined to 8% in 2024, while that for Indians/Asians is at 2%.

The median age of 29 years in 2023 is the sixth-highest in Africa, behind Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, the Seychelles, and Mauritius. By 2043, South Africa’s median age is expected to increase to 34 years.

The country’s population is expected to grow to approximately 69 million by 2030 and 77 million by 2043. Its average total fertility rate fell from 3.7 births per woman in 1990 to around 2.2 in 2023. South Africa is expected to reach a replacement level of 2.1 births by 2028. However, large inward migration flows from the wider region have introduced uncertainty in these forecasts. Our Current Path includes net inflows of two million migrants to South Africa from 2024 to 2043.

In addition, the population is slowly ageing. Whereas nearly 6.6% of South Africans were 65 years old and older in 2023, by 2043, that portion is expected to increase to 10.7%. While this is not a significant trend compared to many developed countries experiencing rapid ageing, it does indicate a gradual demographic shift that will increase healthcare costs, given the expenses associated with treating non-communicable diseases typical of older populations. At the same time, a smaller child population could provide a much-needed opportunity for quality improvements in education.

Chart 3 presents a population distribution map for 2023.

The average population density in South Africa is two persons per square kilometre, roughly equivalent to the average for Africa. The density ranges from the dense metropolitan areas of Johannesburg to the sparsely populated plains of the Karoo in the Northern Cape. The coastal areas of KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape are more populated, while the Northern Cape, with its arid climate, has the lowest population density. There is considerable population movement between provinces. The Eastern Cape, Limpopo, and KwaZulu-Natal generally record the highest rates of outward migration, while Gauteng and the Western Cape experience the highest rates of inward migration, as people seek economic opportunities. This migration puts pressure on urban areas, increasing demand for housing, infrastructure and basic services.

Climate change also intensifies resource insecurities, contributing to intra- and inter-provincial migration. Factors such as drought in the Northern Cape province and soil erosion and degradation in the provinces of Limpopo and the Free State drive people, particularly those with low incomes, to migrate to urban areas in search of better opportunities.

Immigration trends from StatsSA reveal a steadily growing migrant population, dominated by young adults in the region, particularly from Zimbabwe and, to a lesser extent, Mozambique, Lesotho, and Malawi, who mostly gravitate towards the Gauteng province. Zimbabwe leads in sending students for higher education, while Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo) and Somalia are significant sources of refugees. Migration inflows have become an emotional issue in South African politics, with accusations that foreigners are involved in crime and taking jobs from South Africans.

Chart 4 presents the urban and rural population from 1990 to 2043.

South Africa’s cities and urban areas have undergone significant transformation over the past century, driven initially by apartheid policies, industrialisation and economic opportunities. Steady migration from rural areas to cities and towns led to a sharp increase in urbanisation. At the start of the 20th century, only about 10% of the population lived in urban areas. By 1960, nearly 47% of the population resided in urban areas and by 1987, this figure had surpassed 50%, marking a significant shift towards urbanisation. By 2023, 66% of South Africa’s population lived in more than 1 200 cities and towns connected by a complex network of roads and highways. South Africa is the 3rd most urbanised country in SADC, after Botswana and Angola. By 2043, 72% of South Africans are expected to reside in urban areas.

Apartheid-era policies still have a bearing on today’s urban and rural spaces. The former Group Areas Act, which relegated black communities to peripheral townships, created a fragmented urban landscape characterised by long distances between former black, coloured and Indian residential areas and places of work, high transportation costs and inadequate infrastructure. Similarly, rural areas, including former homelands, were systematically marginalised, leaving a legacy of deep-seated economic and social challenges such as unemployment, inadequate infrastructure and high levels of poverty.

Several policies have been implemented over the past three decades to address these disparities with mixed results. The Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), launched in 1994, aimed to improve housing and infrastructure in disadvantaged areas. The Integrated Development Plans (IDPs), introduced in 2000, sought to promote coordinated and sustainable urban development, with some success. Strategic Development Plans (SDPs) and the National Spatial Development Framework (NSDF), introduced in 2018, guide urban growth, emphasising spatial justice, economic efficiency and environmental sustainability. In rural areas, the Comprehensive Rural Development Programme (CRDP), initiated in 2009, aims to improve living standards through infrastructure development, agricultural support, and sustainable livelihoods. Meanwhile, the Integrated Sustainable Rural Development Strategy (ISRDS), introduced in 2000, coordinates government efforts to enhance service delivery and infrastructure. The Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act (SPLUMA), enacted in 2013, provides a uniform framework for spatial planning and land use management across the country.

Despite the numerous initiatives, significant challenges remain if the country is to achieve cohesive and inclusive development in both urban and rural areas.

Chart 5 presents GDP in market exchange rates (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path from 1990 to 2043.

South Africa is caught in a classic middle-income growth trap and, since 2007/8, has been growing more slowly than most upper-middle-income countries (UMICs) globally. The trap is the result of the skewed, two-legged structure of its economy, which features a small but skilled and highly productive private sector, a relatively small informal sector, and a large, poorly skilled and unproductive, economically inactive sector, with a substantial public sector situated somewhere between these extremes. South Africa’s challenges are rooted in apartheid but have been worsened by the global financial crisis of 2007/8, the impact of poor (and bad) governance, widespread corruption to the extent that it bordered on the capture of the state by criminal elements, lack of electricity availability and the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic was followed by two years of modest growth, but lagged afterwards.

Addressing the nation on 21 April 2020, President Cyril Ramaphosa sought to turn the COVID-19 crisis into an opportunity, promising ‘not merely to return our economy to where it was before the coronavirus, but to forge a new economy in a new global reality.’ That, he argued, required a new social compact to accelerate the structural reforms needed to reduce the cost of doing business, promote localisation and industrialisation, overhaul state-owned enterprises and strengthen the informal sector. However, little has come of these promises, and the modest post-COVID recovery has not extended to the job market or the broader economy. The official unemployment rate increases yearly, and average incomes have not recovered to their pre-COVID-19 levels.

To understand why the country is growing so slowly and forecast how it will likely develop over the next 20 years, the subsequent analysis considers the standard sources of economic growth: the contributions of labour, capital, and multifactor productivity (known as MFP or technology). Labour productivity in South Africa has declined for several years and is below the average for other UMICs. Additionally, low capital per worker is a significant drag on economic growth. MFP is also lower than in comparable countries, and the drag that low human capital has on growth is discussed in the Demographics and Health section below.

In the Current Path, South Africa’s growth rate slowly improves to 2.8% per annum in 2043; however, the average rate from 2024 to 2043 is a modest 2.4%, which is comparable to the average for African UMICs but below the global average for UMICs, at 3.7%. Yet, even at this modest rate, the size of South Africa’s economy (at MER) will increase by 60% from US$392.1 billion in 2023 to US$628.3 billion in 2043.

Chart 6 presents the size of the informal economy as a percentage of GDP and percentage of total labour (non-agriculture), from 2020 to 2043.

Although data on South Africa’s informal sector differ between sources, it is apparent that the country has a small informal sector (at 13% of GDP) compared to Namibia (17%) and Botswana (19%), two upper-middle-income countries that share similarly high levels of inequality. The South African informal economy is also smaller as a percentage of GDP than the global average for UMIC countries.

Only around 18% of South Africa’s labour force was employed in the informal sector in 2023, around five percentage points below the average for UMICs in Africa and three percentage points below UMICs globally.

South Africa’s informal sector is expected to decline slightly to 12% of GDP in 2043, although its absolute size is projected to increase from US$49 billion to US$75 billion. The relatively small size of its informal economy and the limited number of informal workers contribute to inequality, extreme poverty, and high levels of unemployment, as work in the informal sector is included in the associated definition of employment as applied by the International Labour Organisation (ILO).

South Africa's rates of entrepreneurship and self-employment are alarmingly low. Many of the country’s working-age population are not economically active, highlighting the urgent need for more entrepreneurial opportunities and a shift in the labour market dynamics.

South Africa’s rigid labour market exacerbates its structural unemployment, in addition to measures such as constraints on skilled inward employment and an absence of large-scale programs that provide low-skilled entrepreneurs with business skills. Instead, the government has rolled out an extensive social grants program and sought to grow employment in the public sector. The extent of South Africa's unemployment challenge is alarming. In 2023, the ILO found that South Africa had the highest unemployment rate globally, after only Eswatini, in part reflecting the country's small informal sector. According to Statistics SA, in mid-2024, 12.4 million South Africans did not work, and the unemployment rate was 42.6%. Around 740 000 South Africans enter the labour market each year, and given slow growth and a capital-intensive economy, the number of unemployed people increases annually.

Chart 7 presents GDP per capita in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043, compared with the average for the global upper-middle-income group.

South Africa’s GDP per capita peaked in 1981 and declined after that as apartheid and global isolation took their toll. The economy started to recover after the historic political transition in 1994, and from 1999 to 2008, the GDP per capita grew rapidly. Growth slowed after the 2007/8 global financial crisis and plateaued during the administration of Jacob Zuma from 2009 to early 2018. In 1990, with the end of apartheid, South Africa’s GDP per capita was US$4 138 above the average for upper-middle-income (UMICs) countries globally. By 2023, it was US$5 614 below. In the Current Path, it will further drop by 2043 to around US$13 480 below the UMIC average. In 2023, South Africa’s GDP per capita was US$12 580 and is expected to grow only modestly to US$14 750 by 2043. Compared to the average for UMICs, South Africa has been stagnating. Years of steady deindustrialisation, weak investment, a growing social-grant-dependent population and lack of adequate investment in critical areas such as education have undermined South Africa’s growth, particularly during the ruinous administration of President Zuma.

This starkly contrasts with countries like South Korea and Taiwan, which historically had lower GDP per capita figures than South Africa but have since surpassed the country’s per capita income.

South Africa’s historical inequalities, high unemployment rates and social disparities have been exacerbated by the country’s low savings rate since it limits the financial resilience of individuals and reduces the availability of domestic capital for investment. These factors contribute to sustained poverty, as economic opportunities are constrained, and social and economic mobility is limited.

Chart 8 presents the rate and number of poor people in the Current Path from 2020 to 2043.

In 2022, the World Bank updated its poverty lines to 2017 constant dollar values, now using US$2.15 per person for extreme poverty and US$6.85 as the poverty line for upper-middle-income countries (UMICs) such as South Africa.

Monetary poverty only tells part of the story, however. In addition, the global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) measures each person’s overlapping deprivations across ten indicators in three equally weighted dimensions: health, education and standard of living. The MPI complements the international US$2.15 a day extreme poverty rate by identifying who is multidimensionally poor and also shows the composition of multidimensional poverty. The UNDP estimates MPI for South Africa at 6.3% in 2021, with an additional 12.2% classified as vulnerable to multidimensional poverty.

Using the extreme poverty line of US$2.15 per day, 21% or 13.3 million South Africans lived in extreme poverty in 2023, declining slightly to 18% or 13.6 million people in 2043. At the US$6.85 income level, the portion of people living in poverty in South Africa was 62% (equivalent to 39.6 million) in 2023. Although the rate will modestly decline to 58% in 2043, the number of poor people will increase to 44.4 million in 2043. These numbers are more than double the average for UMICs globally. Among the eight UMICs in Africa, only Namibia has higher rates of monetary poverty than South Africa.

On its current development trajectory, South Africa will struggle to reduce poverty because of its extraordinarily high levels of inequality and unemployment, its relatively modest economic growth forecasts and its relatively small informal sector. Since its first democratic elections in 1994, economic growth has consistently been too low to create jobs for the flood of annual new entrants to South Africa’s labour market and those previously unemployed. Thus, poverty in South Africa is widespread, and inequality is amongst the highest in the world. According to the Global Inequality Update 2024, published by the World Inequality Lab, the top 10% of South Africans capture more than 85% of the country's wealth. In contrast, the bottom 50% of the population has never captured more than 5% to 10% of South Africa's national income.

Social grants from the government already support around a third (28 million) of South Africans. They play an important role in constraining poverty and inequality growth.

Chart 9 depicts the National Development Plan of South Africa.

Ahead of South Africa's first democratic elections in 1994, the African National Congress (ANC) and its allies released the Reconstruction and Development Plan (RDP), followed shortly thereafter by the 1996 Growth, Employment, and Redistribution (GEAR) plan. In 2006, GEAR was replaced with the Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative for South Africa (AsgiSA) to reduce poverty and unemployment more rapidly. GEAR and AsGISA departed markedly from the RDP, shifting government policies decidedly into a pro-market direction, and would provide fertile ground for an internal campaign within the ANC and its alliance partners that would lead to President Thabo Mbeki's resignation as president in 2008 and after a brief presidency by Kgalema Motlanthe, Jacob Zuma became president after the 2009 elections. Zuma resigned in February 2018, shortly after Cyril Ramaphosa was elected as president of the ANC.

Following the global financial crisis, the Zuma government formulated and released three successive economic strategies: the New Growth Path (NGP), the Department of Trade and Industry's Industrial Policy Action Plan, and, in 2012, the National Development Plan (NDP). President Zuma also announced a Nine-Point Plan at the 2015 State of the Nation speech.

Twenty-five part-time commissioners to the National Planning Commission worked on the NDP, and nominally it remains the official long-term development plan, although the ten-year review of the NDP, released in September 2023, found that its vision of a future South Africa has yet to materialise.

At the heart of our current developmental impasse has been a failure to keep the NDP in focus and at the centre of our developmental trajectory as a country. Instead of keeping the long-term plan in view and using it to inform planning and implementation across government, the NDP was paid little more than lip service, reinforcing incoherent planning and poor implementation.

In President Ramaphosa’s 2019 Budget Speech, he identified the pattern of operating in silos that has led to a lack of coherence in planning and implementation and made monitoring and oversight of the government’s program difficult. To respond to these challenges, he announced the District Development Model, consisting of a process by which joint and collaborative planning was to be undertaken at local, district and metropolitan levels to enable the three spheres of government to work together, with communities and stakeholders, to plan, budget and implement in unison.

Frustration about slow progress was also evident when the National Treasury released its 2019 paper, Economic Transformation, Inclusive Growth, and Competitiveness: Towards an Economic Strategy for South Africa, which identified six structural reform areas, the estimated impact of which would be to increase GDP by 2–3 percentage points over ten years. These include improving industrial and trade policy implementation, export competitiveness and ‘harnessing regional growth opportunities.’ The South Africa Economic Recovery and Reconstruction Plan (EERP), released in 2020, emphasised new investments, new industries and new tradable products as the country transitioned to low-carbon energy and includes ‘re-orienting trade policies and pursuing greater regional integration to boost exports, employment and innovation’ as one of its critical structural reforms. It was followed, in October 2020, with the announcement of Operation Vulindlela as a joint initiative with National Treasury, with its focus on energy, logistics, water and telecommunications, as well as reforms to the visa system.

During the national elections in May 2024, support for the ANC, which had governed South Africa since 1994 with an absolute majority, plummeted. In July 2024, it and several other parties agreed to form a coalition government (calling it a Government of National Unity (GNU)) to share power and achieve common goals. Announcing the agreement, President Ramaphosa resolved to ‘dedicate the next five years to actions that will advance three strategic priorities: Firstly, to drive inclusive growth and job creation. Secondly, to reduce poverty and tackle the high cost of living. Thirdly, to build a capable, ethical and developmental state.’

The Technical page explains the eight sectoral scenarios and their relationship to the Current Path and the Combined scenario. Chart 10 summarises the approach.

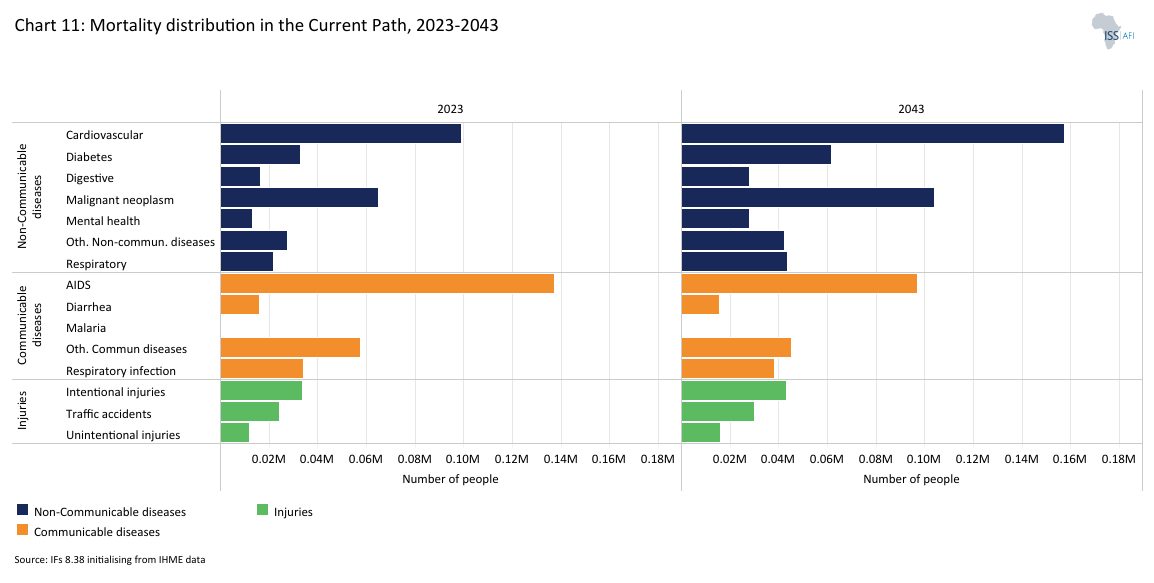

Chart 11 presents the mortality distribution in the Current Path for 2023 and 2043.

The Demographics and Health scenario for South Africa includes interventions to reduce the infection rate for HIV, reduce AIDS death rates as percentage of HIV infection rate, reduce the incidence of cardiovascular disease as well as for diarrhoea, diabetes, malignant neoplasm, respiratory infections, child mortality from infectious disease, maternal mortality rates, and increase the provision of improved sanitation and safe water. It also reduces malnutrition, obesity, smoking by men, the stunting rate for children under five and injuries from vehicle accidents.

The high levels of severe and acute malnutrition combined with high levels of inequality, poor health and a high disease burden constitute a long-term driver of low human productivity. As a result, South Africa’s poor human capital endowment is the most significant drag on multifactor productivity, followed by social capital. In summary, the drag that human capital has on productivity in South Africa reflects low levels of government efficiency since the country’s expenditure on health (8.3% of GDP) is above the average for upper-middle-income countries (UMICs) globally, including those in Africa. Its spending on education, also a large contributor to human capital, is at 6.6% of GDP and similarly above the global average for UMICs (4.7%) but below the average for Africa’s UMICs (5.3% of GDP, including South Africa).

Compared to non-African UMICs, Africa’s eight UMICs have much younger populations and some, including Namibia and Botswana, have been severely affected by HIV/AIDS. South Africa had a 2023 median age of 29.1 years compared to a global average for UMICs at 36.9 years, and has the largest HIV epidemic globally. Communicable diseases typically dominate in younger populations, and, as a result, South Africa (and other UMICs in Africa) underwent their epidemiological transition, when deaths from non-communicable diseases exceeded those from infectious diseases, shortly before 1990, much later compared to other countries at similar levels of development. The transition was reversed shortly after that as a result of HIV/AIDS and its significant spike in deaths from infectious diseases until 2019, when effective treatment saw AIDS deaths decline to the extent that the country again went through its epidemiological transition. This unique pattern is also visible in neighbouring Botswana and Namibia. Had it not been for that, South Africa’s mortality rates would have followed international trends, meaning deaths from non-communicable diseases would rapidly outpace those from infectious diseases as the population ages and the disease burden shifts.

The effect of HIV/AIDS in South Africa is still significant several years after the disease peaked. Average life expectancy, for example, at over 64 years in 1990, plummeted to 52 years by 2005, and by 2023, had only modestly recovered to 66 years, while the average life expectancy for UMICs globally has increased from 68.6 years to 77.1 years in that time. Resistance to the roll-out of antiretroviral treatment from President Thabo Mbeki during his presidency between 1999 and 2006 would delay the effective roll-out for several years. Eventually, during his second term, popular pressure would see antiretroviral therapy scale up, and its subsequent free rollout would cause substantial health improvement.

Discoveries of cheap, long-lasting drugs to avoid infection and the available treatments for prevention and treatment provide a positive future. The most exciting is a twice-yearly injection with a potentially affordable drug, lenacapavir, that fully protects against HIV infection. For that reason, the interventions on AIDS mortality in the Demographics and Health scenario leads to a decline to 78 000 deaths in 2043, compared to 109 000 in the Current Path. In 2023, 137 000 deaths were due to AIDS.

Still, similar to many other UMICs, South Africa faces a double burden of disease with a steady rise in more expensive non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular disease and malignant neoplasm in the presence of significant, long-standing infectious disease prevalence.

For many years, the government has sought to address the many challenges that are faced in the health sector by, for example, committing to the Sustainable Development Goals (2015) and Universal Health Care (2019), setting three main objectives for the health system (and its reform process): (i) to ensure equity in access to health services irrespective of ability to pay; (ii) the quality of health services should be good enough to improve the health of those receiving services; and that (iii) the cost of using healthcare services should not put people at risk of financial harm. The momentum has, however, stalled in recent years with a singular focus on developing a single health system financing model, the National Health Insurance (NHI).

Because of poverty and other factors, many South Africans generally do not pursue a healthy lifestyle. Despite being a food-producing nation, a significant portion of South Africa’s population struggles with malnutrition in various forms, including undernutrition (resulting in stunting and wasting) and overnutrition (resulting in obesity). Males also smoke in larger portions than in other comparable countries. Sixty-eight per cent of women of reproductive age are overweight or obese, and 31% of men. The high prevalence of non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease and hypertension, is all linked to obesity, which is among the top 10 causes of death in South Africa. The problem is particularly severe among mothers and children. Thus, 21% of children under five are stunted.

Undernutrition increases the risk of infectious diseases. The 2018-2023 National Food and Nutrition Security Plan was developed to comprehensively respond to high malnutrition rates, but with disappointing results.

The Demographics and Health scenario models the impact of a comprehensive approach that emulates the impact of reforms that provide for competent management, administration and clinical oversight and governance; establishment of a national health information system; and steps to improve decision-making across the private and public sectors.

In 2023, infectious disease death rates per thousand people were 3.8, non-communicable death rates 4.3 and injuries 1.1. On the Current Path, the 2043 rates will be 2.5 from infectious disease deaths, six from non-communicable diseases and above 1.1 from injuries. In the Demographics and Health scenario, the rates will be lower by 17% and 8%, respectively. Deaths from injuries also decline, though modestly.

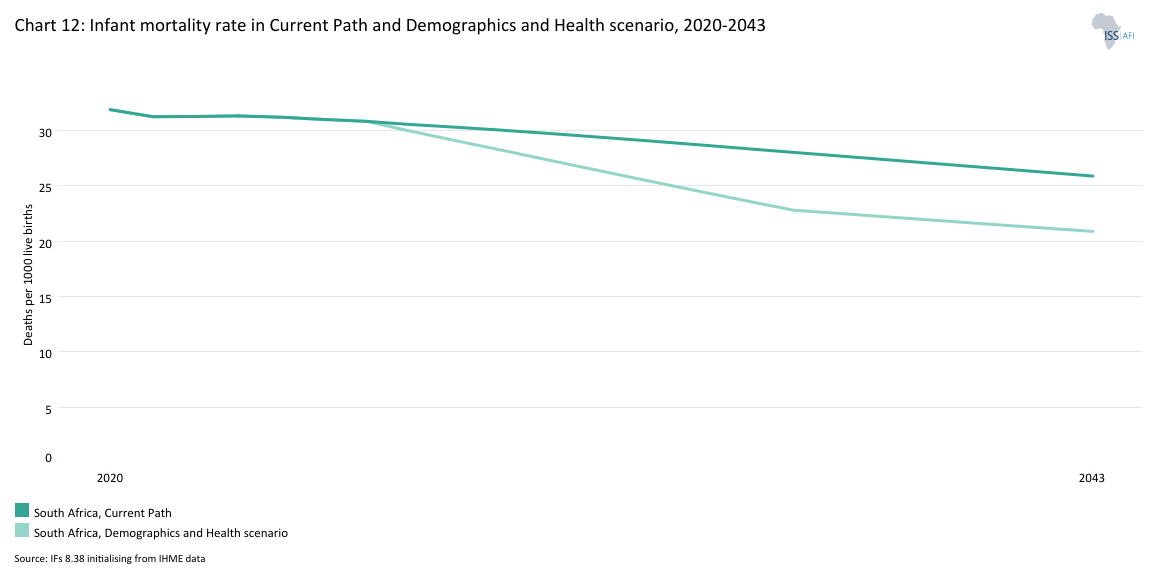

Chart 12 presents the infant mortality rate in the Current Path and the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

The infant mortality rate is the probability of a child born in a specific year dying before reaching the age of one. It measures the child-born survival rate and reflects the social, economic and environmental conditions in which children live, including their health care. It is calculated as the number of infant deaths per 1 000 live births and is an essential marker of the overall quality of the health system in a country.

In 2023, infant deaths per 1 000 live births in South Africa were nearly three times the average of UMICs globally (31.3 vs 10.6), primarily due to HIV infections and a high burden of influenza-associated mortality rates. Between 7 000 and 12 000 seasonal influenza-related deaths are estimated to occur annually in South Africa, of which half are in the elderly and about 30% in HIV-infected people. And, while the average for upper-middle-income countries (UMICs) globally can expect a near halving of infant mortality rates by 2043 (to 6.6), the Current Path for South Africa in 2043 is still extraordinarily high at 25.9 deaths per 1 000 live births. At that point, infant mortality rates in South Africa will even be above the rates for low- and lower-middle-income countries globally, mainly due to the lingering impact of HIV/AIDS.

In the Demographics and Health scenario, which includes aggressive interventions on reducing HIV/AIDS, South Africa’s rates of infant deaths per 1 000 live births will decline to 20.9 in 2043, a reduction of 19% compared to the Current Path.

South African expenditure on health has been constant at roughly 8% of GDP since 2012, slightly higher during the 2019-2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Compared with other UMICs, South Africa's expenditure on its health sector as a portion of government expenditure is high, but more is needed, given the burden of disease discussed previously. However, the country has a large and well-funded private healthcare system that serves around 27% of the population, paid through individual contributions to health insurance or medical insurance plans. The private healthcare system is sophisticated but characterised by over-servicing and inflated costs, while the public healthcare system, responsible for 71% of the population, has steadily deteriorated over time.

Evidence of the failures to address or strengthen stewardship, governance, leadership and management in the public sector is now overwhelming, with corruption and irregular expenditure endemic at all levels. According to senior medical experts writing in the South African Medical Journal in 2024, many parts of the public health system are now unable to deliver their assigned services, or an acceptable quality of care. As a result, the gap between the private and public healthcare systems is significant. For example, the amount spent on health care for each person with a medical aid scheme in South Africa is five times the amount spent on each person who relies entirely on public health facilities. The distribution of health professionals between the private and public sectors and urban and rural areas is also large.

In response, the government published a National Health Insurance (NHI) Green Paper, followed by NHI pilot projects in 2012. The NHI white paper in 2015 proposed the achievement of universal health coverage. The NHI is a centralised, national insurance fund from which the government will buy healthcare services from healthcare providers in both the public and private sectors. In May 2024, President Ramaphosa signed the NHI Bill, to be phased in by 2028. There is broad support for the plan, but concerns remain about various aspects, including the funding model, the extent of corruption and maladministration in the Department of Health and the implications for the private healthcare system.

In 2024, shortly after the elections that saw the formation of a Government of National Unity, a seven-member multidisciplinary panel of experts appointed by the Academy of Science of South Africa published its report that reflected on the widespread problems in the country’s public healthcare system, including a large number of managers in acting positions, frequent changes in senior leadership, worse health outcomes than similarly resourced countries, and overall deterioration of morale and trust. The panel recommended eight steps to address key governance issues:

- Define and communicate a clear public value mission and mandate for each level of the health service and each governance actor.

- Update legislation and governance structures to insulate them from vested interests and give them executive rather than merely advisory functions.

- Delegate authority appropriately to each level and within levels of the health system.

- Get the right people – ethical people with the appropriate competencies – into leadership and management positions within the health system.

- Surround managers and leaders with functional, fit-for-purpose systems so that they can do their work.

- Support managers at every level with the resources, understanding and ability to build teams and attend to the relationships that make complex systems work.

- Harness the authentic potential of community participation to ensure appropriate, respectful and responsive health services and monitor health service outcomes and processes.

- Act on dereliction of duty and acts of corruption and protect whistle-blowers.

The extent to which South Africa can feed, educate and create employment opportunities for its large working-age population is determined by its ability to improve its health.

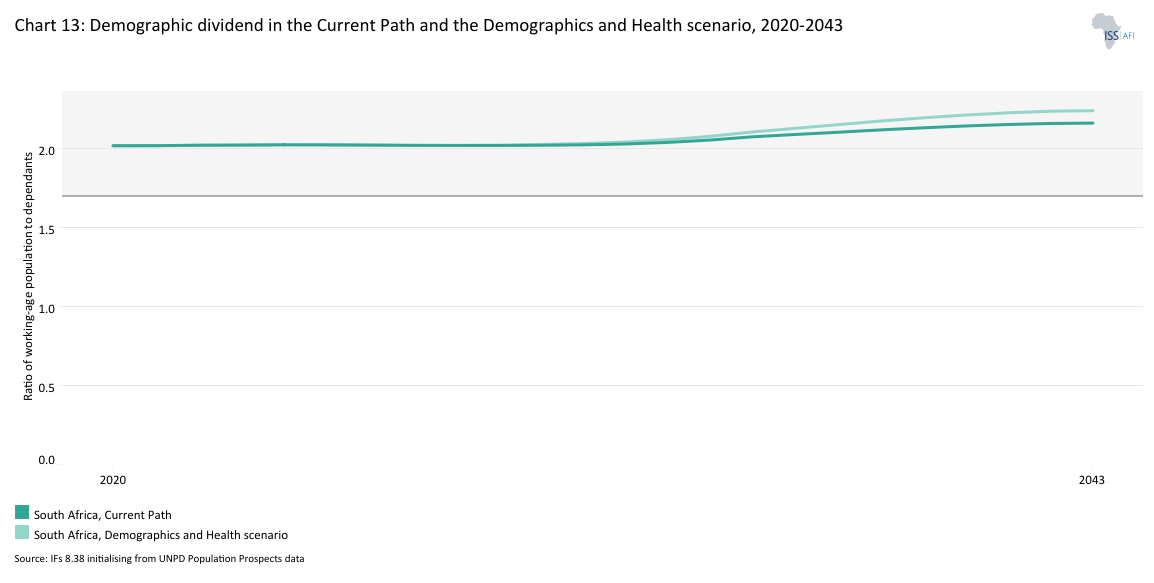

Chart 13 presents the demographic dividend in the Current Path and the Demographics and Health scenario from 2020 to 2043.

The demographic dividend is the window of economic growth opportunity when the ratio of working-age persons to dependants increases from 1.7 to 1 and above.

South Africa entered a potential demographic window of opportunity around 2003 when the ratio of working-age persons (15 to 64 years of age) to dependants exceeded the ratio of 1.7. Still, the country has been unable to translate that dividend into more rapid economic growth and higher incomes. Only six other African countries are in this potentially fortunate position: the island states of Mauritius, Seychelles and Cape Verde, and three countries in North Africa (Morocco, Tunisia and Libya).

By 2023, the ratio had improved to 2:1. Still, the country had experienced a steady decline in GDP per capita for several years, given the impact of COVID-19, state capture, poor governance, poor health and an underperforming education system. Labour productivity in South Africa has been on a slow decline for over a decade. Still, there are prospects for improvements with the end of the COVID-19 crisis and expectations of improved government effectiveness and economic growth following the establishment of the Government of National Unity in 2024. South Africa’s working-age population ratio will peak at 2.2:1 in 2043, before declining. As health and education indices improve, they will reduce the considerable drag that poor human capital exerts on economic growth.

While labour's contribution to growth improves due to a healthier population, this also results in a larger elderly population (life expectancy in 2043 will be 73.7 years in the Demographics and Health scenario, instead of 70.4 in the Current Path, with female life expectancy 6.1 years above that of men).

In the Demographics and Health scenario, South Africa’s 2043 population will number 76.8 million people, around 164 000 fewer than in the 2043 Current Path. The scenario positively influences the working-age population by increasing this cohort to 69.2% compared to the Current Path’s 68.4% in 2043. A larger working-age population means South Africa’s GDP will be US$18.2 billion larger in 2043 than in the Current Path. GDP per capita will be US$310 higher.

Outside Africa, most upper-middle-income countries (UMICs) have passed their peak dividend and are already experiencing a declining ratio of working-age persons to dependants. With sufficient capital and technology, the larger pool of workers relative to dependants in Africa could accelerate rates of economic expansion.

Chart 14 shows crop production and demand in the Current Path from 1990 to 2043.

South Africa is among the few African countries achieving food security at the national level and is a net exporter of agricultural goods. Its varied climate supports one of the most diverse agrarian sectors globally, producing crops such as maize, citrus fruits, wine grapes, sugarcane, apples and pears. It also boasts a vibrant poultry and livestock industry.

The agricultural production and demand data in our analysis are initialised from data provided on food balances by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), which contains data on numerous agricultural types. However, in the model, the forecast is disaggregated into crops, meat and fish, presented in million metric tons.

The sector has been steadily increasing production over the past six decades, and export growth to other BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China) have been particularly impressive. However, 2023 proved difficult due to continued load-shedding (electricity outages), animal disease outbreaks and port congestion. Despite these setbacks, the industry demonstrates significant resilience compared to other economic sectors. These challenges include the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated lockdown regulations, the July 2021 unrest that severely impacted the food supply chain, and Russia's invasion of Ukraine, which led to increased costs of critical agricultural inputs and disrupted international trade flows of essential commodities such as fertiliser, wheat, sunflower and rice.

Agriculture in South Africa is a vital sector that plays a crucial role in the economy, food production, employment and poverty alleviation. It is the backbone of rural development, providing livelihoods for a significant portion of the population. During the budget vote in parliament in July 2024, the newly appointed agricultural minister noted that the sector contributes an average of 2.8% to the national economy (measured in GDP) and roughly 6% to total employment. Together with food production and processing, agriculture contributes up to 7% to GDP, driven primarily by citrus and maize exports. The country's status as the second-largest global exporter of citrus remains a critical factor in the agro-processing sector’s contribution to GDP. According to the BFAP 2024 baseline report, maize and soybean yields have also multiplied.

The success of South Africa’s agricultural sector is a result of an innovative private sector, which responds to local and international market demands. The industry includes large-scale commercial farms and agribusinesses utilising modern farming techniques and technologies to boost productivity. The backbone of the commercial sector consists of approximately 107 000 commercial farmers, although only a small percentage (some 6.5%) produce the bulk of agricultural output. Early in 2025, the Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy (BFAP) released a comprehensive report on agriculture in South Africa for the period 1994 to 2024 that included the following summary of the sector:

… livestock production, traditionally the largest subsector in our semi-arid country, has shifted from extensive (beef and mutton/lamb on rangeland) to intensive (poultry, dairy, pigs) commodities as shifts in consumer preferences were followed by farmers. This has been enabled by the successes in the field crop subsector. Maize yields have been on their way to quadrupling since the early 1990s, and the country has become self-sufficient in soybeans to the benefit of intensive livestock production, while improvements in white maize production, the country’s staple crop, have benefited lower-income consumers. Finally, the horticulture subsector has shown the importance of access to irrigation water and infrastructure to output, but also to the stabilisation of output. South African producers of fresh produce benefit from our zero-tariff access to the UK and EU markets, from our counter-seasonal access to markets due to the fact that we are largely in the same time zones as our traditional markets. It is fair to say that fruit growers across the entire spectrum of fruit represent the most successful subsector in South African agriculture. This achievement has been supported by a rapidly growing tree nut sector, as well as a range of speciality berry crops.

In contrast, subsistence and smallholder farms—mainly located in areas under traditional authority—face challenges such as smaller plot sizes, inadequate infrastructure and poor access to critical inputs. Many farms acquired through the government’s land reform program are underperforming, with more than 50% of agricultural land classified as low to medium potential. Targeted support and infrastructure development are necessary to make these lands more productive.

The 2003 Comprehensive Agricultural Support Programme (CASP) intends to assist emerging farmers by providing resources and infrastructure to improve productivity.

South Africa's agricultural sector also suffers from rainfall variability, including droughts, severe flooding and water scarcity. The 2015/16 El Niño event, which caused the worst drought since 1904, significantly impacted maize and wheat production. Water scarcity, worsened by inadequate irrigation infrastructure and competing demands from different sectors, limits crop production, especially in regions with limited, reliable water sources. Soil degradation, driven by erosion, nutrient depletion and poor land management practices, contributes significantly to declining productivity. Moreover, insufficient investments in sustainable farming techniques and soil conservation efforts leave the sector ill-equipped to counter these challenges, leading to yield stagnation in the Current Path.

Despite production keeping pace with demand in past decades, South Africa risks becoming a net food importer in the coming years without further investments in infrastructure and agricultural yields. On the Current Path, crop demand will outstrip production beyond 2031, leading to a deterioration in food security. By 2043, South Africa will face a 15.7 million metric ton shortfall in its crop production compared to demand.

To counter these challenges, the Agriculture and Agro-Processing Master Plan (AAMP), adopted in 2022, seeks to enhance productivity, inclusivity and sustainability. By focusing on increasing yields, expanding production, improving infrastructure, and adopting sustainable practices, the plan aims to drive long-term growth and resilience in the agricultural and agro-processing industries. The Agricultural Policy Action Plan (APAP) complements these by focusing on value-chain development and smallholder support. The Comprehensive Agricultural Support Programme (CASP), initiated in 2003, also provides resources to help emerging farmers involved in land reform.

According to the Bureau for Food and Agriculture Policy (BFAP), irrigated maize yields in certain provinces, such as the Eastern Cape (dominated by large portions of land under communal tender), could reach up to 12.5 metric tons per hectare, a significant increase from current levels of 5.07 metric tons per hectare in commercial farming and 2.36 metric tons in subsistence farming. Other vital crops, such as wheat, soybeans and citrus, can increase production if infrastructure constraints, such as road access, reliable electricity and efficient irrigation systems, are addressed.

BFAP is optimistic in its medium-term outlook, noting that investments in improved irrigation systems, water management and new technologies can enable South Africa to maintain its net exporter status. In particular, the expansion of irrigated agriculture and the use of climate-resilient crops are essential for addressing the challenges posed by climate variability.

The subsequent Agriculture scenario mirrors these policies through ambitious yet feasible increases in yields per hectare, additional groundwater withdrawal, an aggressive rollout of irrigation systems, efforts to reduce food loss and waste, and the expansion of rural access roads. South Africa could significantly boost its agricultural productivity by investing in these areas. The country can also increase land under cultivation by using available state-owned land and conducting tenure reform in the former homeland areas.

By addressing these challenges and investing in critical areas such as irrigation and soil management, South Africa’s agricultural sector could increase average yields to 7.2 metric tons per hectare by 2043 (compared to 5.5 on the Current Path), enabling total crop production to rise in the scenario to 92.2 million metric tons instead of 70.2. The increase would secure South Africa’s food supply and allow for increased export earnings, reinforcing the country's role as a critical player in the SADC region’s food security.

Chart 15 presents the import dependence in the Current Path and the Agriculture scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

South Africa remains one of the few food-secure African countries, contributing significantly to the region's food supply. However, future projections are less optimistic. The Current Path is that South Africa’s reliance on agricultural imports (crop, meat and fish) will grow to 17% of its domestic demand by 2043, indicating increased vulnerability to global market fluctuations.

The Agriculture scenario presents a much more hopeful trajectory with South Africa producing a surplus equivalent to 3.4% of its demand by 2043. It illustrates that South Africa could maintain its status as a net exporter with targeted interventions. In the scenario, total agricultural exports will increase to 22 million metric tons, equivalent to US$5.2 billion, compared to the 8.1 million metric tons (valued at US$2.4 billion) in the Current Path for 2043. Additionally, imports will decrease to US$5.2 billion, compared to US$6.4 billion in the Current Path.

The proposed interventions would also roughly maintain the agricultural sector’s value-added contribution to GDP, which is 2.3% in 2023, in contrast to the reduction to 1.7% by 2043 on the Current Path. The scenario illustrates the benefits that flow from strategic investments in agriculture to safeguard food security, bolster economic growth and reinforce South Africa's role as a critical food supplier in the region.

Chart 16 depicts the progress through the educational system for primary gross enrolment, primary completion, lower-secondary gross enrolment, lower-secondary completion, upper-secondary enrolment, upper-secondary completion, tertiary enrolment, and tertiary completion in the Current Path (for 2023 and 2043). The numbers reflect the percentage of of-age children that attend.

With the advent of democracy, South Africa's education system undertook the enormous task of redressing the legacy of apartheid, particularly the chronic underfunding of black learners. While post-apartheid South Africa has made notable strides in access to education, with gross enrolment rates in primary and secondary levels exceeding 100%, the quality and completion rates remain concerning, particularly at the upper-secondary and tertiary levels. Policy incoherence, poor management and corruption, aggressive teacher unionisation, an insufficient focus on technical and vocational education at secondary and tertiary levels, and neglect of early childhood development, all stymied progress. These matters are now attracting more government attention.

A 2016 comprehensive report from the University of Stellenbosch found that around 60% of South African children could not read for meaning by the end of Grade 3, and identified four binding constraints to improving educational outcomes, particularly for learners from low-income backgrounds:

- Weak Institutional Functionality - most pronounced at the provincial level, where ineffective governance and administration impede the implementation of national policies.

- Undue Union Influence - contributed to resistance against performance evaluations and accountability measures for teachers.

- Inadequate Teacher Knowledge and Skills, with many teachers lacking the required content knowledge and pedagogical skills to deliver quality literacy and numeracy education.

- Wasted Learning Time: Inefficient use of school hours and limited learning opportunities.

The COVID-19 pandemic compounded these issues, with school closures and rotational timetables exacerbating educational inequalities, particularly in poorer communities. A subsequent 2021 study painted a bleak picture, finding that 81% of Grade 4 learners in South Africa could not read for meaning in any language and suggested that learning losses due to the pandemic set reading outcomes back a decade.

South Africa’s education budget does not appear to be insufficient. In 2023, South Africa's government allocated 6.6% of its GDP to education, almost two percentage points higher than the average for upper-middle-income countries (UMICs) globally and higher than the average for UMICs in Africa. With a spending commitment equivalent to some high-performing Scandinavian countries, South Africa does worse than Kenya or Tanzania, which have GDP per capita of less than one-fifth of South Africa’s. Instead, poor management, corruption and lack of prioritisation are endemic. While throughput along the education funnel is high, the problems are overwhelmingly related to poor quality.

In recent years, there has been some progress towards addressing these challenges. The South African education system is gradually shifting towards greater coherence, with an increased focus on technical and vocational training to prepare students for the demands of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The 2013 White Paper for Post-School Education and Training and the subsequent National Plan for Post-School Education and Training 2021-2030 envisioned a significant increase in enrolment at Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) and Community Education and Training colleges. The goal is for these institutions to enrol over two-thirds of all post-school education students, thus expanding opportunities for practical, skills-based learning. Yet, in mid-2024, 16 648 out of the 22 511 public schools had no libraries, 18 551 had no laboratories, and 14 839 had no computer centres, according to a report by the Department of Basic Education titled: Education Facility Management System.

Despite its substantial budgetary allocation, the South African education system grapples with significant challenges rooted in its historical context and current systemic inefficiencies. South Africa is the most critical learning underperformer relative to GDP per capita among low- and middle-income countries.

In addition to practical matters relating to overcrowding, lack of basic facilities and teacher shortages, recommendations relating to improved education include the need for policy coherence across the various departments and levels of government (the most significant problems appear to lie at the provincial level), better management and aggressive efforts to eliminate corruption in the education sector, create a culture reflecting lifelong learning for teachers, as well as find a balance between teacher unionisation, parent involvement and government line responsibility.

The Education scenario addresses some of these shortcomings through ambitious yet attainable improvements in the South African education system, including higher intake, transition and graduation rates from primary to tertiary levels. It also emphasises gender parity, additional vocational training at the secondary level, and an increase in the share of science and engineering graduates. Perhaps most importantly, the scenario includes interventions to improve the quality of primary and secondary education.

Between 2023 and 2043, primary and lower-secondary completion rates will improve significantly. Whereas, the Current Path is that 68% of of-age children will finish upper-secondary education in 2043, the number improves to 83% in the Education scenario. Instead of 17.2% of the of-age group graduating at tertiary level, the rate will be 23.3% in 2043.

Chart 16 highlights a positive trajectory in improving throughput. However, improvements in teaching quality, learning resources and institutional management remain elusive, as do the broader objectives of equity and economic competitiveness.