The likely impact of mounting global tensions in sub-Saharan Africa

The region must step up its development agenda to cope with a more uncertain global environment and increasing geopolitical tensions.

Geoeconomic fragmentation (GEF) – defined by the International Monetary Fund as a policy-driven reversal of integration, often guided by strategic considerations – has increased dramatically since Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine. This has had severe ramifications for sub-Saharan Africa.

Widespread sanctions on Russia have spiked the price of food, fertilisers, and energy, hurting the most vulnerable in a region not yet recovered from the effects of COVID-19.

The region has especially felt the impact because of its high dependence on food and fertiliser imports, and its limited trade partner diversification. Climate change-related shocks such as floods and droughts have also reduced domestic agricultural production in sub-Saharan Africa and deepened the effects of GEF in the region.

Multilateral institutions need to ensure that economic integration continues to act as a growth catalyst for all countries

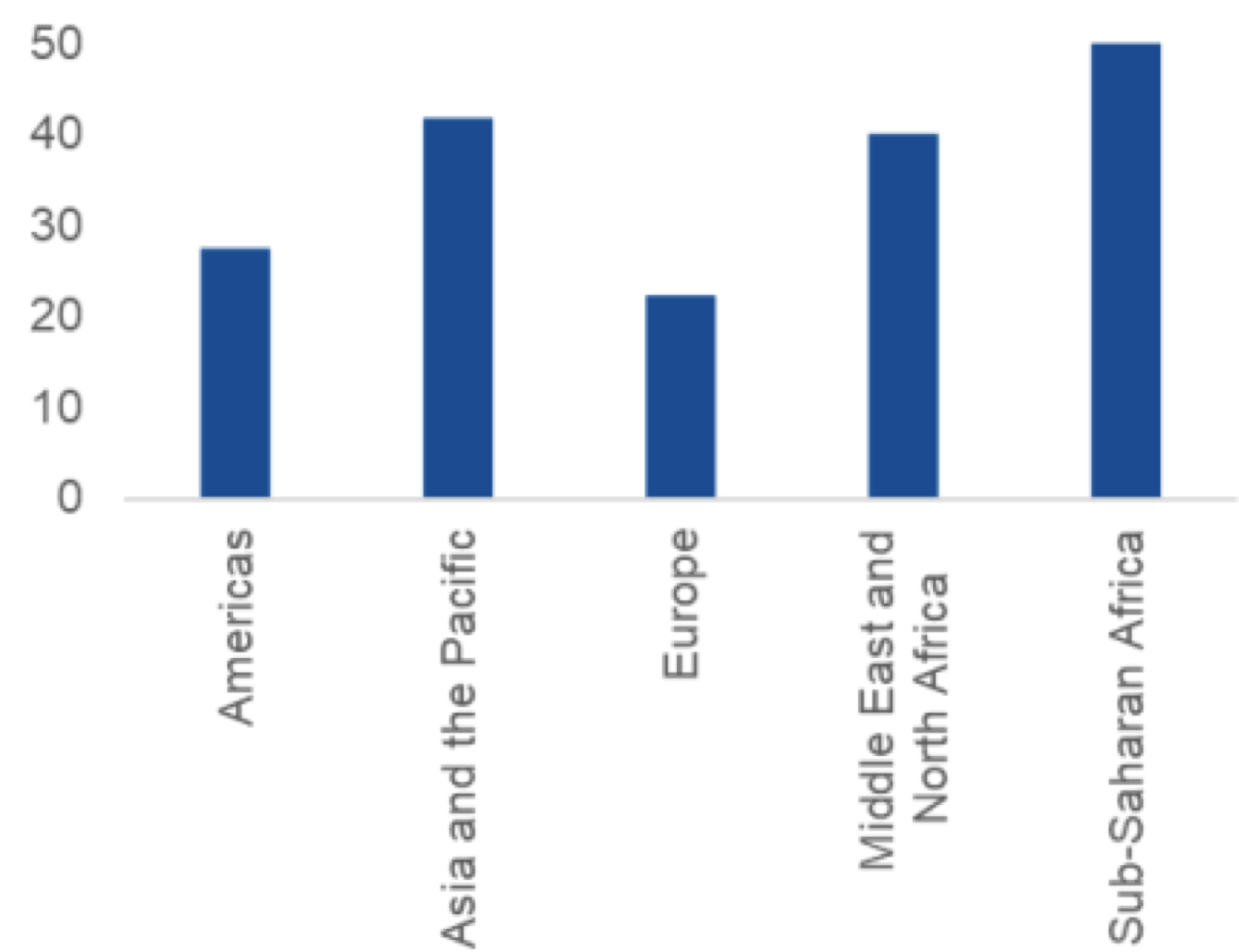

As part of a 2023 note on fragmentation in sub-Saharan Africa we evaluated different hypothetical scenarios – based on the model by Bolhuis et al. (2023) – to gauge how the region could be affected by GEF. Under a severe scenario where the world splits into two distinct trade blocs, one centred around China and the other around the United States (US) and European Union (EU), sub-Saharan Africa would lose around half of its current trade (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Trade at Risk of Geoeconomic Fragmentation

(Percentage of total international trade)

Sources: Eora Global Supply Chain database and IMF staff calculations.

Notes: Trade at risk refers to exports and imports to and from another bloc under a scenario of ‘geoeconomic fragmentation’ where all trade is cut off between countries in US/EU- and China-centred blocs. Countries that trade more (imports and exports in 2019) with the US than with China are put in the US/EU-centred bloc, and vice versa.

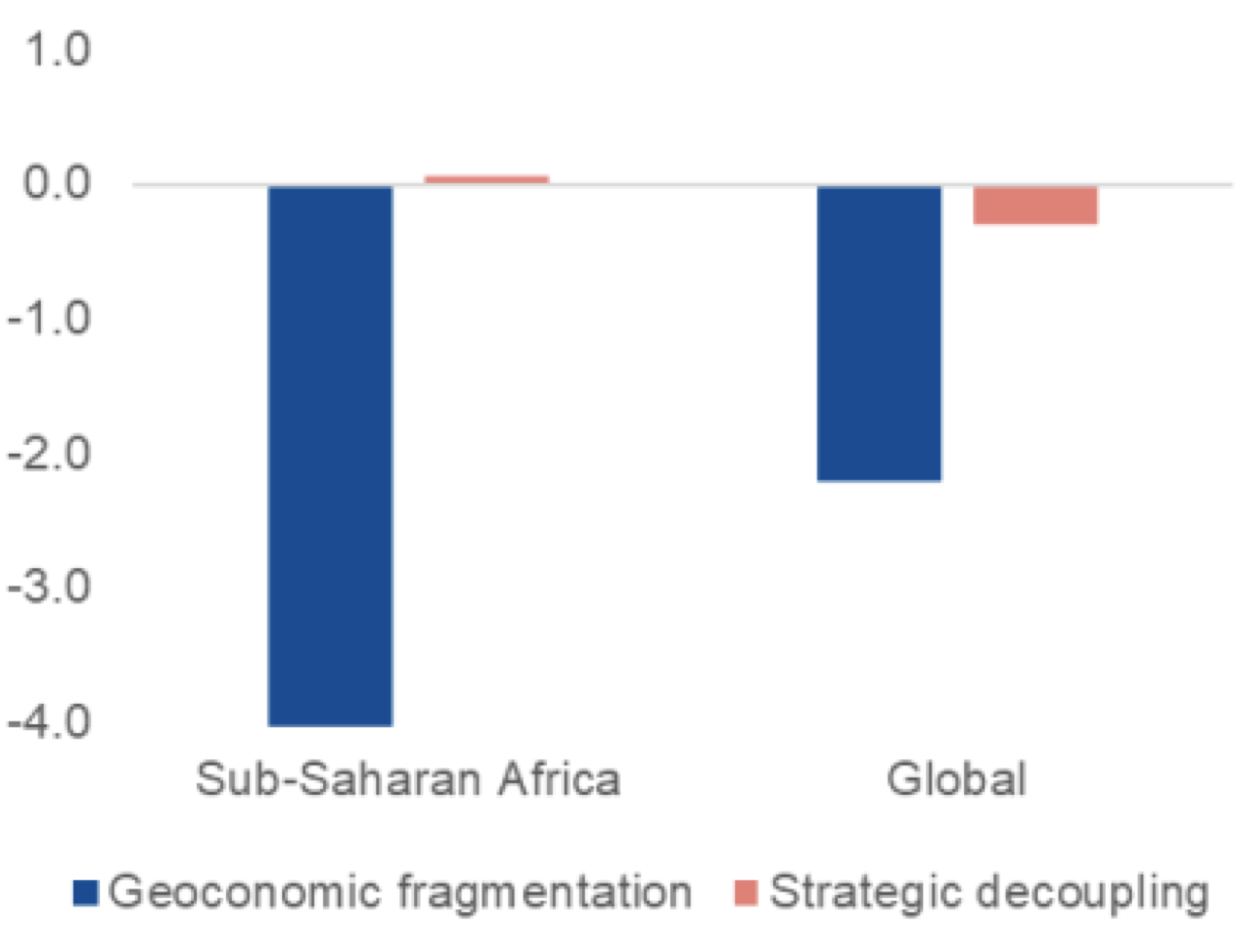

Under this scenario, where the region would lose access to key export markets and experience higher import prices, the median sub-Saharan African country would experience a permanent decline of 4% of real gross domestic product (GDP) after 10 years relative to a no-fragmentation baseline (Chart 2). To put things in perspective, these estimated losses are smaller than those during the COVID-19 pandemic but larger than those during the 2007-8 Global Financial Crisis. Further, declines are bigger in countries that are more integrated into global trade and in countries that initially traded more with the bloc from which they are severed.

Chart 2: Estimated Real GDP Impact SSA and World

(Percent deviation from a no-fragmentation scenario)

Sources: Bolhuis et al. 2023 and IMF staff calculations.

Notes: Bars highlight annual losses for median country after 10 years relative to a no-fragmentation baseline. Under a severe ‘geoeconomic fragmentation’ scenario, all trade is cut off between countries in US/EU- and China-centred blocs. Countries that trade more (imports and exports in 2019) with the US than with China are put in the US/EU-centred bloc, and vice versa. Under a less severe scenario of ‘strategic decoupling’, trade ties are cut only between Russia and the US/EU, and all trade ceases between the US/EU and China in hi-tech sectors, leading to some diversion of trade flows towards Africa.

The above results are not exhaustive as they just cover the effects of trade fragmentation, in a region that could also be affected by a disruption in external financial flows. If, for example, capital flow ties were cut with either bloc consistent with the preceding severe scenario, the region could lose about $10 billion of foreign direct investment (FDI) and official development assistance inflows, equivalent to about 0.5% of GDP a year. This assessment on potential financial losses, however, does not account for any reshuffling under a general equilibrium model.

In the long run, trade restrictions and a reduction in FDI could also hinder much-needed export-led growth and technology transfers. Further, for countries looking to restructure their debt, deepening GEF could also worsen coordination problems among creditors.

However, not all is bleak, and a milder geoeconomic fragmentation scenario may create new trade partnerships for the region, especially for oil exporters.

In another scenario in which trade ties are cut only between Russia and the US-EU while sub-Saharan African countries continue engaged globally (‘strategic decoupling’ – see Chart 2), trade flows would be diverted partly towards the rest of the world and intra-regional trade in sub-Saharan Africa may increase. Because some countries would benefit from access to new export markets and cheaper imports, the region would not incur an aggregate GDP loss relative to the baseline (Chart 2). Oil exporters supplying energy to Europe would especially gain in such a scenario.

Countries need to build resilience and continue structural reforms

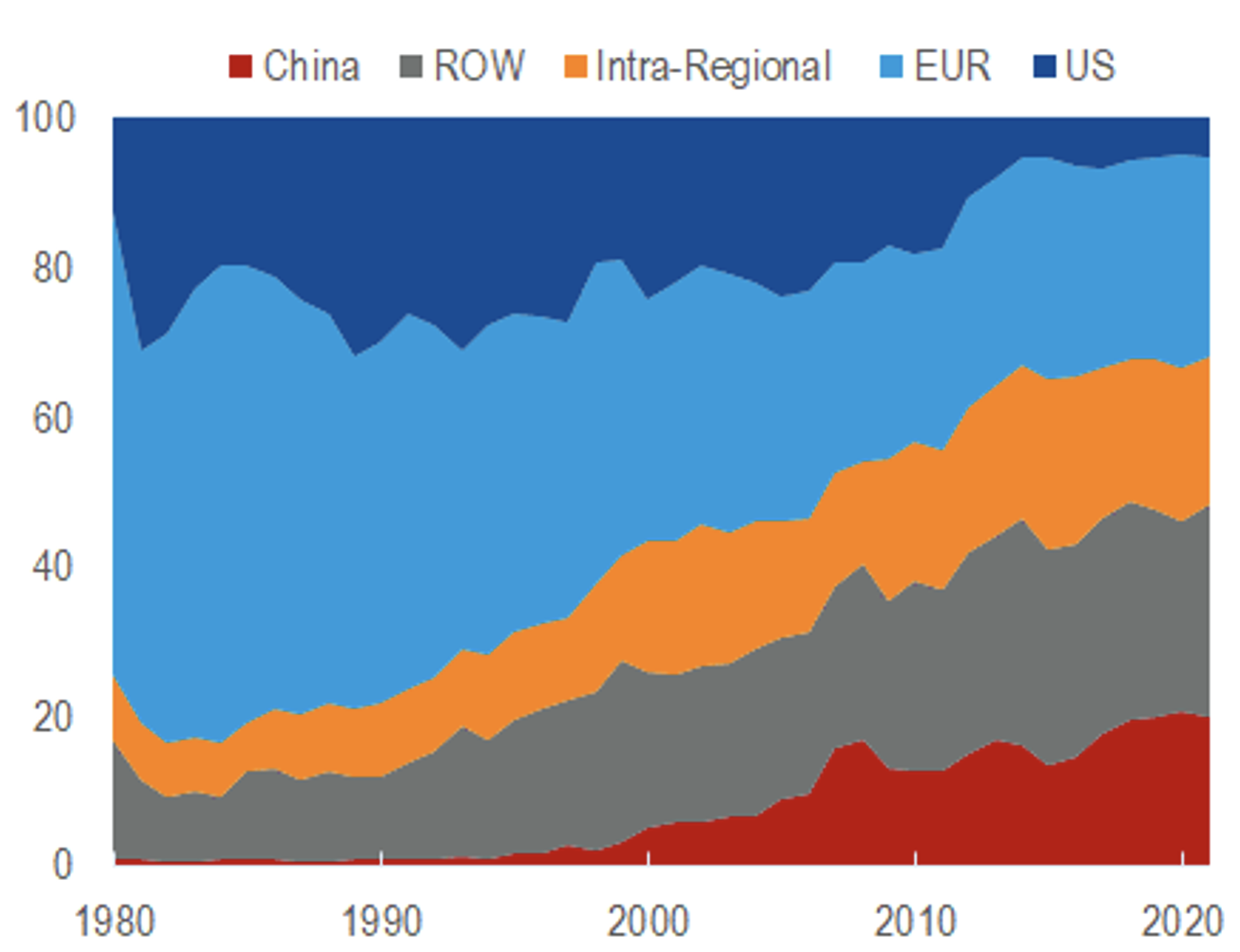

The waves of globalisation over the past 20 years also help explain why the region would be strongly affected by GEF. The main reason has to do with a trade integration pattern that largely links the region to rising new trade partners, like China, which could end up in an antagonistic position with the region’s traditional trade partners, like the US and EU.

Riding on the tailwinds of China’s globalisation since the early 2000s, the value of exports from sub-Saharan Africa to China increased tenfold over this period, largely driven by oil exports. Oil exports represent more than half of the region’s total goods exports to China but make up only one third of the region’s goods exports to the rest of the world.

The region’s trade openness – measured as imports plus exports as share of GDP – doubled from 20% of GDP before 2000 to about 40% driven by increasing Chinese demand. The region has largely benefited from the takeoff of China and other emerging markets, with its share of total exports going to the US and EU declining from almost 80% in the 1980s to around 40% in recent years. Now, sub-Saharan African exports to the world are almost evenly split between those going to the EU and US and those to China and the rest of the world (ROW) (Chart 3).

Chart 3: Sub-Saharan Africa: Exports to key destinations, 1980-2021

Source: Based on data from IMF DOTS

Considering this recent outlook, the region needs to step up its development agenda to cope with a more uncertain global environment and the increasing GEF tensions. It needs to think into a longer horizon. One that helps it benefit from global integration and within-region inter-connectivity, such as through the ongoing regional trade integration under the African Continental Free Trade Area, while investing in its long-term agenda (IMF Report on AfCFTA, 2023). That is, human capital, business climate, infrastructure, technology, and financial systems.

Sub-Saharan Africa must strengthen the agenda that helps it sustain long-term development, remain integrated and become more attractive to FDI. Given the tightening financing options (the ‘funding squeeze’) that the region faces, countries must expand the pool of domestic resources, such as improving domestic revenue mobilisation and deepening domestic financial markets.

The region urgently needs to tackle its most pressing short-term issues, including the effects of GEF, while solidifying its long-term development agenda. The current situation is a challenge for the region. It could leave it with even less human capital investment, and deeper concentration in primary commodity production and trade, which is a deviation from its much-needed diversification efforts and green energy transformation.

What the exact outcomes will be from fragmentation and polarisation, and whether these trends will continue, are uncertain. What is clear, however, is that countries need to build resilience and continue structural reforms.

Widespread sanctions on Russia have spiked the price of food, fertilisers, and energy

Multilateral institutions have a role to serve: they need to ensure that economic integration continues to act as a growth catalyst for all countries. They can facilitate the dialogue promoting the gains of global integration, stress the costs from protectionist practices, and push for cooperation in areas of common interest – including food security, climate change, and debt resolution.

Disclaimer: The views in this blog reflect those of the authors and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: The authors based this blog on their fragmentation note with co-authors Marijn Bolhuis, Hamza Mighri and Henry Rawlings

Image: sleepyfellow/Alamy Stock Photo