Building disaster resilience in African cities: the need for a holistic approach

The complexity of the urban environment must be embraced in order for the continent’s cities to become resilient to large-scale disasters.

Urban centres in Africa have experienced significant advancement in economic, social, and educational development over recent decades. Consequently, since 1960, Sub-Saharan Africa’s urban population has grown from 15% in the 1960s to about 42% in 2021.

It has become one of the most rapidly urbanising regions among all developing regions on the planet. The African Development Bank estimates that the steep rate of urbanisation in Sub-Saharan Africa will continue for the foreseeable future, and will reach 60% by 2050.

Chart 1: Rate of urbanisation in developing regions

(Source: World Bank, 2023)

Although these urbanisation trends have started to contribute to raising large parts of the population out of poverty, there have also been negative consequences. The large influx of new arrivals to urban areas has meant that existing infrastructure and urban planning capacity have been overwhelmed in many urban settings and led to the proliferation of sprawling informal settlements.

The United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) estimates that up to 51% of urban inhabitants in Sub-Saharan Africa currently reside in slums and informal settlements. These areas are characterised by a lack of access to basic services and high rates of socio-economic vulnerability and are located near environmental and human-induced hazards such as rivers, coastlines, steep slopes, and factories. These circumstances create the prevailing conditions for large-scale disasters to occur.

African cities need to invest in making the existing infrastructure required for providing basic services to communities more disaster-resilient

The consequences of these prevailing conditions are already becoming evident in much of Sub-Saharan Africa with the number of disaster occurrences increasing over time. This is especially true of hydrometeorological disasters such as tropical cyclones Idai and Kenneth, and the large-scale flooding that affected hundreds of thousands of people in urban communities in Mozambique, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Madagascar, and South Africa in recent years.

When trying to make sense of the destruction to infrastructure, economic livelihoods and loss of life following such disaster events in African cities, there is often a rush by experts and politicians to lay the cause of the event at the feet of a major geopolitical issue such as climate change. Climate change will play a role in changing the regularity and intensity with which disasters will occur. But making it the panacea for why disasters occur in urban settings in Africa is problematic, and leads to superficial solutions that are unlikely to contribute to building urban disaster resilience on the continent.

Instead, holistic approaches and interventions are needed that take note of the complex sets of drivers that make Africa’s cities susceptible to disasters. Some organisations operating in the region have recognised the need for holistic solutions, most prominently the Technical Centre for Disaster Risk Management, Sustainability and Urban Resilience (DIMSUR). DIMSUR has developed an urban resilience-building tool called CityRAP that is already creating benefits for some of the most at-risk cities in Southern Africa, such as Morondava (Madagascar), Zomba (Malawi), Chokwe (Mozambique) and Moroni (Comoros).

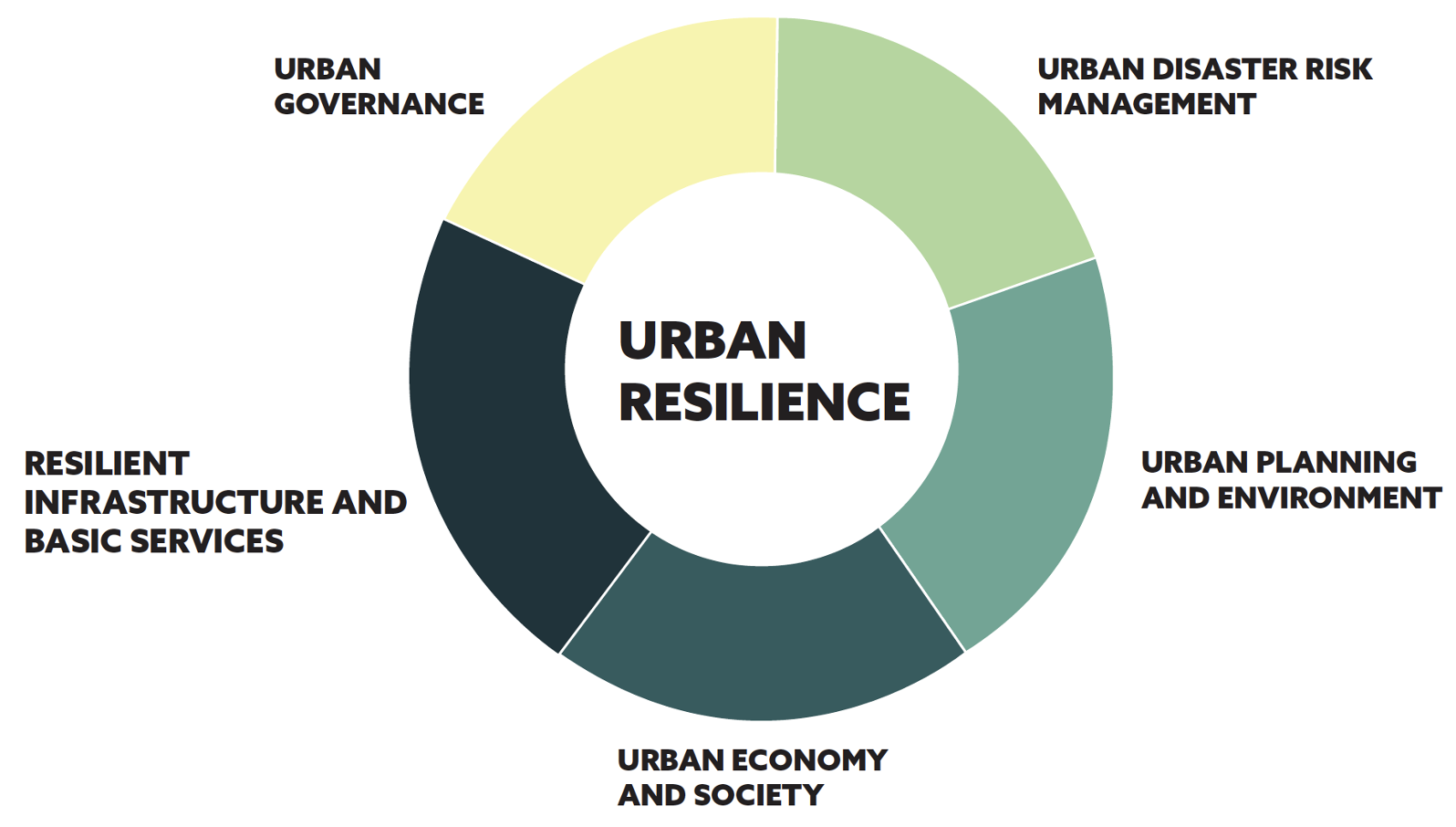

Chart 2: DIMSUR CityRAP tool

The CityRAP tool identifies five overarching spheres that need to be addressed in African cities to ensure disaster resilience is built. The first is the urban governance sphere. Often African urban environments are susceptible to disasters as they are characterised by poor governance practices that are not inclusive of all critical stakeholders that could give insights into how to plan for and reduce the impact of disasters in urban settings. Therefore, a crucial point of departure for building urban resilience is establishing governance platforms that will facilitate the participation of communities, government departments, donors, and non-governmental organisations.

The second sphere that needs attention is improving existing urban disaster risk management mechanisms. Specifically, disaster risk assessments should be regularly carried out and updated to ensure a dynamic understanding of a city’s disaster risk profile. Regular assessments could inform the development of targeted risk reduction interventions.

Disaster risk assessments should be regularly carried out and updated to ensure a dynamic understanding of a city’s disaster risk profile

Urban planning that is cognisant of and manages the hazardous environment in which communities find themselves is the third sphere. By integrating disaster risk reduction and climate change principles into existing urban planning procedures such as the development of spatial plans, public spaces, and upgrading informal settlements, at-risk communities could adapt to and resist the impacts of disasters much more readily.

The fourth sphere to be addressed in making African cities resilient is the need for responsible economic growth. It is important to develop economic nodes (e.g. markets), gather investment support for small and medium enterprises, and provide training to entrepreneurs. Increased economic activity will not only diversify communities’ income sources, making them more adaptable when coping with disaster, but also make them more likely to invest in insurance and concrete risk-reduction measures at their homes.

Finally, African cities need to invest in making the existing infrastructure required for providing basic services to communities more disaster-resilient. Municipal infrastructure in many African cities is old and poorly maintained. When disaster strikes, this infrastructure is destroyed – leaving communities without basic services and exposed to secondary disaster events such as cholera outbreaks, water shortages and civil unrest. Replacing old and decrepit building stock might be expensive, but it provides an opportunity for African cities to integrate climate change adaptation and risk-reduction measures such as bioswales and green roofs into the construction of new infrastructure.

Increased economic activity will diversify communities’ income sources, making them more adaptable when coping with disaster

For African cities to become more disaster-resilient there is a need to move away from one-dimensional analysis, understanding and practical intervention by urban governments, and embrace more holistic approaches such as CityRAP.

Holistic approaches embrace the complexity of the urban environment and ensure that various aspects of the urban socio-economic and environmental ecosystem are enhanced to build urban resilience. These approaches also have the added benefit of ensuring greater collaboration between the government, the private sector, and vulnerable communities to enable more inclusive disaster risk reduction in African cities.

Image: © Joerg Boethling / Alamy Stock Photo