Africa needs more and cheaper debt

The primary responsibility to unlock more finance and cheaper debt lies with Africans, but the international community must help.

Africa’s debt peaked at just above 26% of its gross domestic product (GDP) at the height of the COVID-19 global lockdown in 2020. It is now estimated to have declined slightly to 24% of GDP, equivalent to US$645 billion. Africa does not have less debt than in 2020. Rather, economic growth has resumed after the pandemic, which has increased the size of African economies and hence reduced the debt-to-GDP ratio.

This ratio is not high, particularly compared to countries such as the United States (US) and Japan. Because it is considered low risk, and because the dollar is the world’s reserve currency, US debt is sustainable at more than 120% of GDP, but significantly lower than that of Japan at 262%, which is stuck with a declining population and hence a slow growth economy.

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a debt threshold range of 70% to 90% of GDP is appropriate for high-income countries such as the US and Japan and 30% to 50% for emerging economies, including Africa’s 46 low-income and low-middle-income economies.

The OECD further recommends that a prudent debt target should average 15 percentage points below the debt threshold since exogenous events, such as COVID-19 or Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, could push up interest rates. Domestic developments such as unrest or a coup can also see countries lose market confidence and hence increase their borrowing costs. For that reason, most African countries can only sustain debt levels of 15% to 35% of GDP, according to the OECD, which still would imply that 26% of GDP seems reasonable.

So why are 21 African countries now in or approaching a debt crisis, most prominently Zambia and Ghana? Why do so many African countries suffer from a recurring fiscal deficit?

Why do so many African countries suffer from a recurring fiscal deficit?

Five matters are crucial in considering the debt-to-GDP ratio. The first is how much the debt costs, i.e. the interest rate at which the debt is incurred. According to United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres, Africa pays four times more for borrowing than the US and eight times more than the wealthiest European countries.

The second is the currency in which the debt is held. Currency depreciation regularly increases the public debt stock in many African countries because a significant portion of the debt is in foreign currency. For instance, since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, on average, exchange rate depreciations increased public debt in Sub-Saharan Africa by 10 percentage points of GDP by the end of 2022.

Third, what is the economic growth rate? An expanding economy offsets debt repayments by increasing in size, thus reducing the size of the debt as a portion of GDP.

Africans need to be able to afford much higher debt levels – at least 50% to 60% of GDP

Fourth, how vulnerable is the borrower to exogenous effects? A single-commodity-based economy is, for example, very vulnerable to price swings while a diversified economy where agriculture, manufactured goods and service exports all contribute to earnings is much more resilient.

Finally, prudent financial management is also important. Simply, is the money loaned put to productive use?

Debt repayment as a portion of government revenues, therefore, emerges as a key ratio to watch, as is good financial management. For example, because the US federal government borrows at ridiculously low interest rates, it uses only about 14% of federal spending to service its debt-to-GDP ratio of 120% while poor countries spend up to 40% of government revenues.

The problem is that Africa needs lots of finance to fund its infrastructure requirements. It has the world’s most rapidly growing population that requires more schools, hospitals, roads, harbours, railway lines and other infrastructure every year.

During COVID-19, several countries also undertook social programmes to cushion the effect of the lockdown, adding to their debt burden at a time when their economic growth came crashing down. And so debt as a percent of GDP and debt servicing costs increased. And then African governments have low domestic revenue mobilisation capacity, and government expenditure is often unproductive.

US debt is sustainable at more than 120% of GDP, but significantly lower than that of Japan at 262%

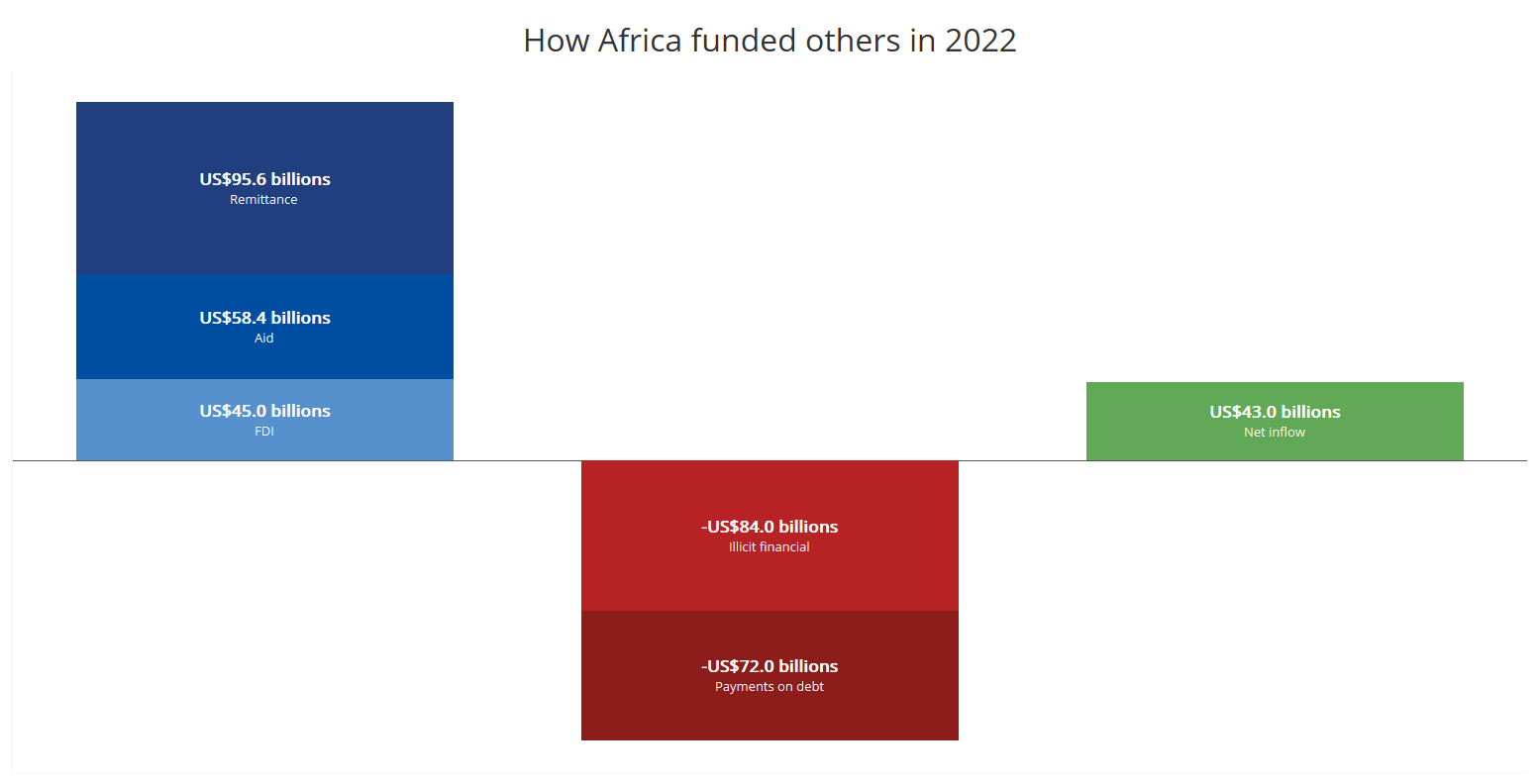

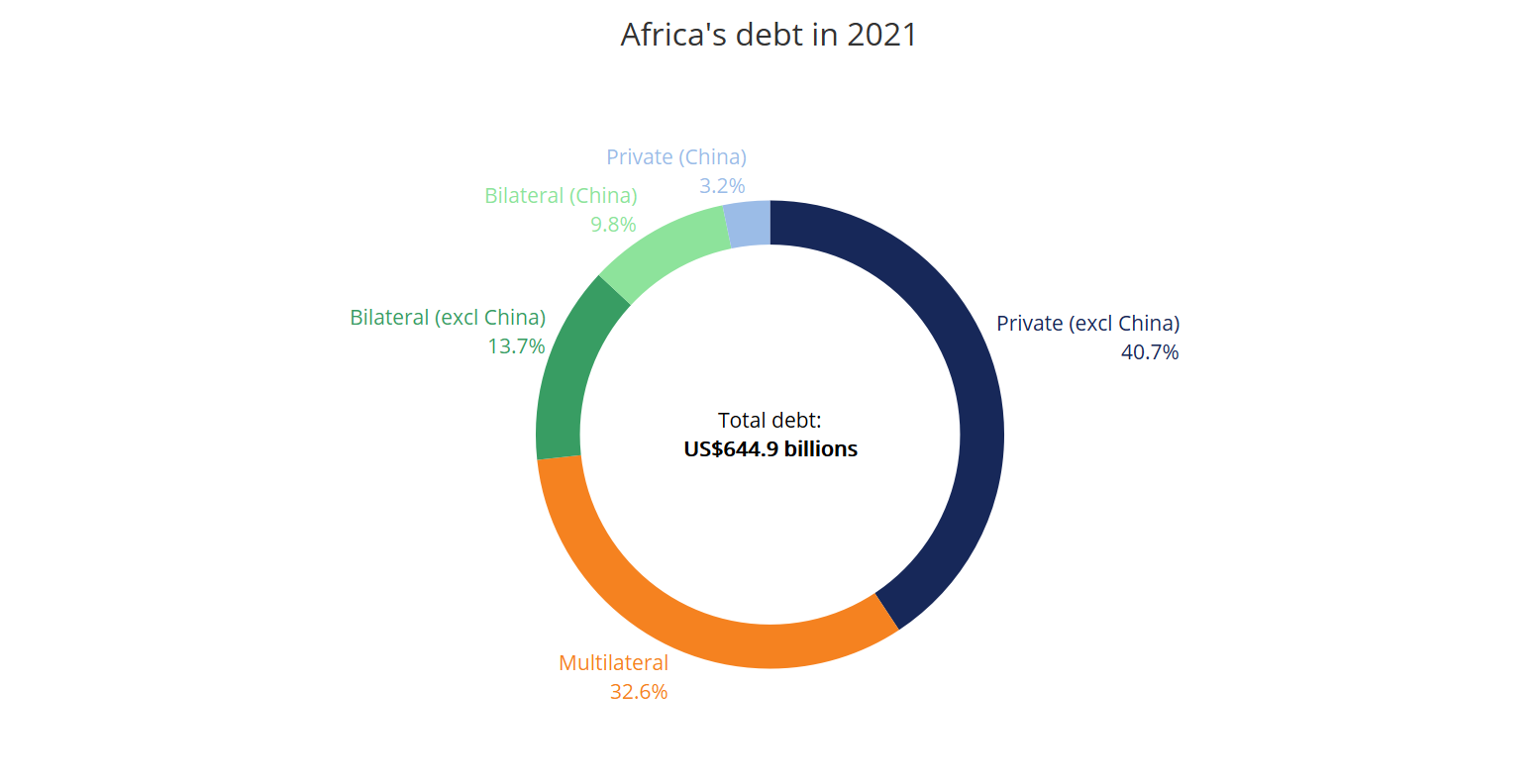

In 2021 Africa owed US$644.9 billion to creditors and will pay US$68.9 billion to service its debt this year, which is about US$13.6 billion more than it receives in aid. The UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) estimates that the continent loses US$84 billion in illicit financial outflows annually.

Once remittances and foreign direct investment are added to the picture, it’s clear that Africa experiences modest annual financial inflows. In 2022 it came to US$43 billion, despite the continent needing more capital than other regions.

Source: UNECA, ONE Campaign, UNCTAD

Source: UNECA, ONE Campaign, UNCTAD

Africans increasingly borrow from private creditors in the West and from China instead of international financial institutions (IFIs) such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. They’re trapped on the horns of a dilemma that requires high levels of government expenditure to fund development and are unable to fund that domestically.

IFI loans are often concessional, which means they are provided at low interest rates but come with conditions related to prudent financial management. Loans from China and private creditors are non-concessional but interest is charged at market rates and, given the high-risk perception premium, punitive interest rates apply.

These are the reasons for the current debt crisis and why Zambia, Ghana, Chad, and Ethiopia recently defaulted. To add insult to injury, once in debt distress, their borrowing costs will increase, and they will be locked out of the financial market.

At the moment the favourite response from most in the West to Africa’s rising debt is to blame China

To avoid default, newly elected leaders sometimes prioritise servicing their foreign debt, such as happened with the incoming William Ruto and Bola Tinubu administrations in Kenya and Nigeria. To service its debt, Kenya didn’t pay civil service salaries in March, for example. And within days of assuming the presidency, Ruto announced additional taxes to foot Kenya’s debt bill. President Bola Tinubu of Nigeria ended 50 years of fuel subsidies that were costing his administration US$11 billion annually. In this way high costs and bad management are directly transferred to the African on the street.

How does Africa get out of this bind? Even developed countries cannot finance their capital needs from domestic revenues alone and need to borrow. As a percent of GDP, Africa’s finance requirements are much higher, although eminently achievable when looking at the amounts of capital available globally. The problem is that it’s simply too expensive on the open market because of the risk perception associated with most African countries.

The primary responsibility to unlock more finance and cheaper debt lies on Africans themselves to improve their financial management and political stability, although it’s also evident that Western credit rating agencies punish us unfairly, and that the IFIs need radical surgery to make them fit for purpose.

At the moment, the favourite response from most in the West to Africa’s rising debt is to blame China since it is Africa’s biggest bilateral lender and owned more than US$84.1 billion of Africa’s debt in 2021. Of this, US$20.9 billion was private debt, and the rest bilateral. The reality, however, is that private bondholders, most of which are in the West, own significantly more of Africa’s debt than China.

There is no silver bullet to this dilemma. It requires a host of responses, starting with the quality of domestic governance and extending all the way to restructuring the voting rights of IFIs. Africans must afford much higher debt levels (at least 50% to 60% of GDP) which is only possible at very low concessional rates. This means someone somewhere needs to offset the additional risk premium we are charged as Africans work to reduce their risk premium through better governance.

Who will grasp this nettle? How can we engineer a common approach to Africa’s development dilemma that includes China, the West, private bond holders and development banks in these times of global tension?

Guterres has published a set of recommendations he intends to table with the 2024 Summit of the Future, coming on top of various others such as the Bridgetown Initiative and the Paris financial summit. Nothing less than a global compact, the entire restructuring of IFIs and a significant amount of funding from rich countries will help unlock the huge amounts of private capital required for Africa’s development.

That is in addition to changing the biased risk premium against Africa by agencies such as Moody’s, Standard and Poor’s, and Fitch. Eventually, African economies need to transform by exporting more value, and there needs to be fiscal discipline, better government revenue collection and political stability. But in the meantime, we need more but cheaper debt.

Image: African Economic Research Consortium