Africa’s instability is putting the brakes on the continent’s development trajectory

Only inclusive economic growth can produce the resources required to alleviate the root causes of instability in conflict-torn countries.

Africa’s current conflict burden reflects a close correlation between poverty and poor state capacity. The factors that drive stability yield both a concerning and a reassuring outlook for the future.

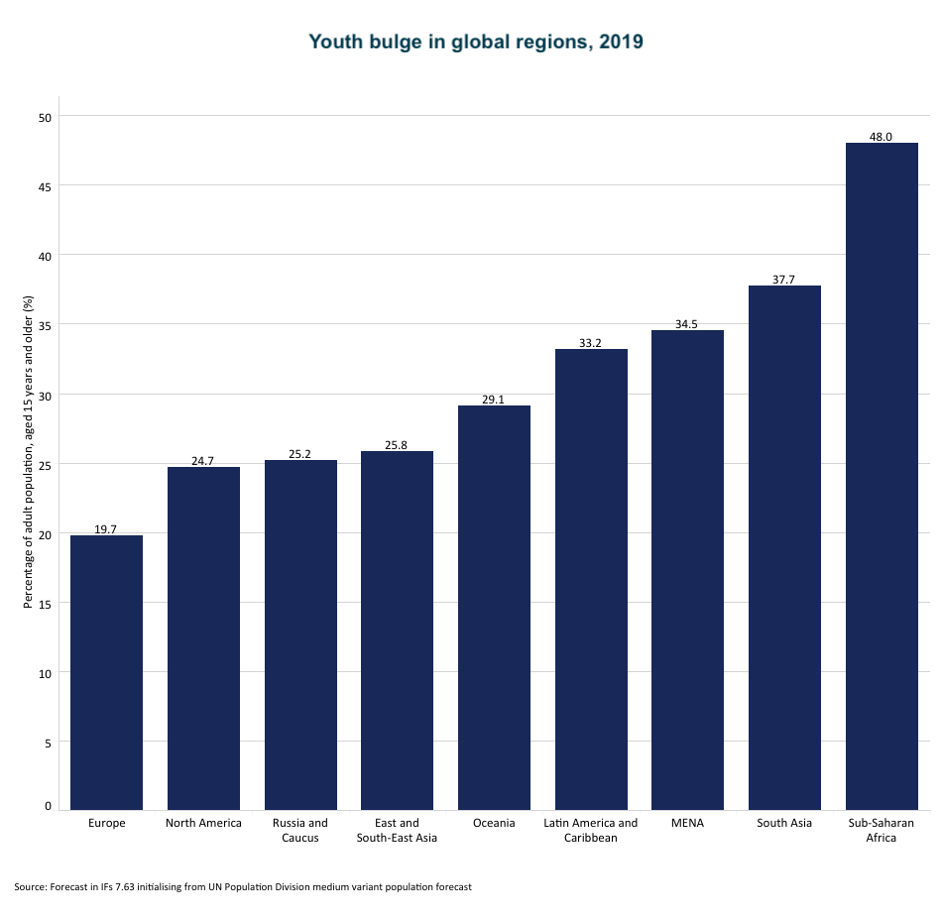

Africa has an exceptionally large youthful population, with a median age of 20 (although rates differ significantly between countries and between rural/urban and income groups). A large male population of between 15 and 29 years old relative to the total adult population is generally associated with an increased risk of conflict and high rates of criminal violence.

This is more pronounced where secondary and tertiary education is expanding along with this type of demographic structure of growing youth cohorts, which leads to increased political violence even in the presence of low rates of youth unemployment. The associated high expectations are hard for governments and labour markets to satisfy, leading to relative deprivation and social unrest.

Both the nature and the periodic trends of conflict have changed in Africa over the past 70 years. Today, fatalities from armed conflict generally seem to be concentrated in a few countries, although the effects can spill over into neighbouring countries, inhibiting growth and creating safe havens for conflict actors. Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, particularly, have seen continuing attacks. The Liptako-Gourma border area among the three countries remains volatile, with a terrorist threat, intercommunal violence and transnational organised crime.

Africa’s current conflict burden reflects a close correlation between poverty and poor state capacity

The effect of climate change on conflict is a threat multiplier that affects socio-economic outcomes with dwindling agricultural incomes, increasing food insecurity, water scarcity and droughts, weakening human health and residential mobility. It is no coincidence that the countries situated in Africa’s Sahel region, such as those mentioned above, are plagued by internal conflict and the effects of a rapidly changing climate driving extreme droughts and other hazard conditions. These effects are even more pronounced in low- and middle-income settings, where the economy is generally closely linked to agricultural production.

Most African governments function as mixed regimes, so-called anocracies, which are prone to instability. Generally, liberal democracies are more stable and peaceful than other regime types. However, the transition from autocracy to democracy is often turbulent, and mixed regime types (so-called anocracies or electoral rather than substantive democracies) are volatile. For example, of the 16 African countries that experienced sustained armed violence in 2021, none are fully democratic.

In addition to the level of democracy, levels of stability depend on sustained economic growth and the means to provide for and enforce security. Developing countries have fewer resources to devote to either security or development. As a result, poor countries are more violent, which in turn means they cannot grow rapidly enough to alleviate the stresses and grievances that lead to the instability in the first place. These countries find themselves stuck in a vicious cycle.

Only inclusive economic growth can produce the resources required to alleviate the root causes of instability in conflict-torn countries in Africa. Before COVID-19, the continent was making steady progress towards improving general living conditions, which translated into stability because government capacity to provide or enforce security increased. This was reflected in larger budgets for the various security agencies.

It will take time for Africa to become more peaceful and less violent

Government spending on security tends to be low relative to the level of insecurity in Africa and compared with spending in other conflict-prone regions, such as the Middle East. The 2019 average for defence expenditure in Africa was 2% of GDP and is expected to track downward to 1.5% of GDP by 2033 based on 2019 figures.

Furthermore, this expenditure is poorly allocated, as the spending inevitably tends to be skewed towards providing security for the governing elite rather than responding to the real security needs of citizens.

Given the continent’s long history of coups d’état and military interference in government, security spending is often divided between competing and overlapping security services as leaders try to ensure that no single agency becomes a threat. The result is that many areas in Africa are unpoliced, with limited government representation and weak institutions that, coupled with extreme poverty, lead to high levels of rent-seeking and corruption.

In Southern Africa, the high level of inequality in countries such as Namibia, Botswana and South Africa presents a potential threat to stability, because the informal sectors in these countries are relatively small compared with those in other countries at similar levels of development. The extent of autocratic repression in countries such as Equatorial Guinea and Eswatini also presents problems if left unattended. Eswatini has already recently experienced recurring bouts of violence. Efforts by certain African leaders to extend their terms in office or effect dynastic succession present obvious problems without the prospects for either democratic change or generational succession.

Addressing violence, instability and armed conflict in Africa requires an ongoing and dedicated response

Stability is essential to unlock economic growth and investment and break the poverty and conflict cycles that plague many parts of the continent. That requires much more African-led peacemaking, peacekeeping and peacebuilding. Increasingly, these functions are led and managed by Africans, largely due to a decline in the willingness of external actors to participate in peacekeeping on the continent combined with the push towards greater ownership.

The evidence on peacekeeping is clear: the risk of conflict recurrence drops by as much as 75% in countries where United Nations (UN) peacekeepers are deployed. It is against this backdrop that the African Union (AU) launched Agenda 2063 as a mechanism to bring together all segments of society to build a prosperous and united Africa. To this end, the AU’s 50th anniversary declaration pledged to end the burden of conflict and all wars by 2020.

This lofty ambition was not achieved and was further complicated by COVID-19, which caused an estimated 30 million more Africans to fall into extreme poverty (living on less than US$1.90 a day) in 2020. This left far fewer resources for government services, including those aimed at providing security. Rising energy and food prices have subsequently placed more strain on government budgets, further restricting spending on security.

The African Futures and Innovation modelling shows the economic benefits of greater levels of stability. Foreign direct investment flows will increase to a level of US$254 billion or 3.7% of GDP by 2043. More stability and foreign investment translate into a bigger economy and improved economic growth. The Stability scenario suggests the following key impacts:

- By 2043, the African economy will be US$468 billion larger than in the Current Path forecast (in market exchange rates).

- By 2043, the average GDP per capita (in purchasing power parity) would be US$7 423, increasing by US$266 above the Current Path forecast for that year.

- Approximately 31 million fewer Africans would be living under the international extreme poverty line of US$1.90 per day, with South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo expected to experience the largest reductions in the percentage of extremely poor people.

- Levels of democracy are likely to increase, with an associated improvement in governance.

Africa is also democratising, and it is difficult for democracies to counter insurgencies

It will take time for Africa to become more peaceful and less violent because it takes long for the necessary structural levers of change to take root. Conflict-affected countries typically have much younger populations than more stable regions, and population structures shift slowly.

The impact of COVID-19 is such that instability will probably increase for several years given that the pandemic led to more hunger, job losses and reduced government revenues, which in turn translate into less service delivery and smaller security budgets.

Africa is also democratising, and it is difficult for democracies to counter insurgencies. Democracies struggle to fight internal wars, particularly low-insurgency type conflicts. In addition, the war in Ukraine is reverberating around the world, affecting the global economy by driving inflationary pressures with the most fragile places always bearing more of the brunt.

Addressing violence, instability and armed conflict in Africa requires an ongoing and dedicated response from the AU, its member states and the international community to provide aid, humanitarian assistance and peacekeeping towards the promise of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Image: UN Photo/Stuart Price